Looking at voters’ values helps explain the UK’s changing electoral landscape, write Paula Surridge, Michael Turner, Robert Struthers, and Clive McDonnell. They look at vote switching between 2015 and 2017, and explain why the two main parties need to understand the values of two specific groups of voters in order to appeal to them.

The period between the 2010 general election and that of 2017 has been marked by very high levels of voting volatility. The collapse of first the Liberal Democrats between 2010 and 2015, and then UKIP in 2017 appears on the surface to have led us back to a two-party system, with Labour and the Conservatives gaining the highest two-party share of the vote since the 1970s. This apparent return to the two-party system masks high levels of individual level volatility as well as the potential for existing (and new) ‘3rd’ parties to be resurgent as the voters struggle to fit themselves into a party system which barely reflects their values and preferences.

Having previously introduced the values clans here, this piece uses this framework to look at vote switching between 2015 and 2017, and considers the values of the clans which had the greatest prevalence of vote switching.

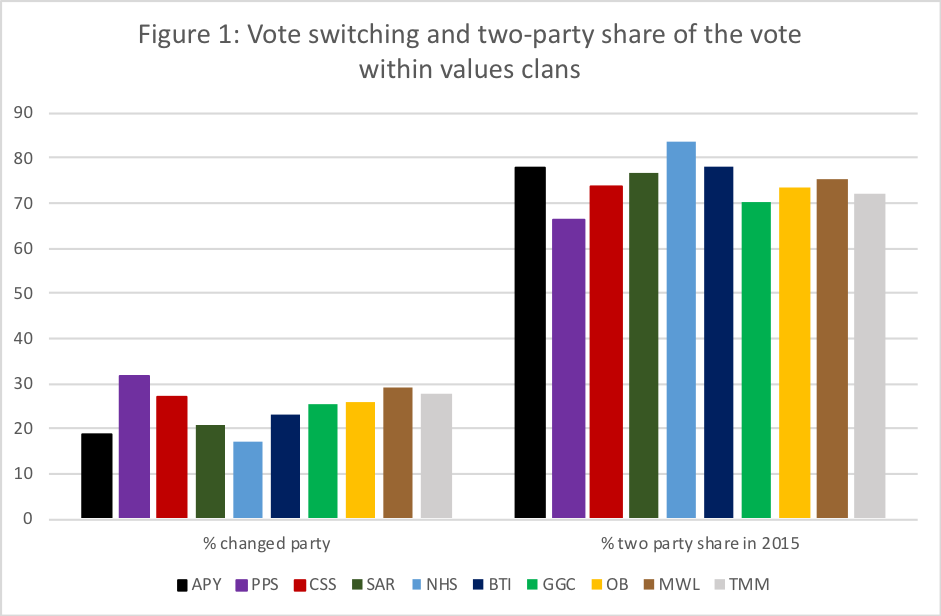

Taking only those who voted in both the 2015 and 2017 elections, we can calculate the proportion who changed parties within each of the values clans. As shown in Figure 1, this proportion was highest among the Proud and Patriotic State clan – who combine left-wing economics with socially conservative values – and lowest among the Notting Hill Society – with broadly right-wing economic instincts. This strongly mirrors the two-party (Labour plus Conservative) share of the vote in each clan and is indicative that much of the switching between parties occurs between a ‘minor’ party and one of the two major parties, with direct switching between Labour and the Conservatives rare. Overall, around 1 in 20 voters switched directly between Labour and the Conservatives between 2015 and 2017.

Note: see here for a detailed explanation of the various clans illustrated above.

Note: see here for a detailed explanation of the various clans illustrated above.

Considering how the different clans behaved, and the characteristics of those with higher levels of switching helps us understand where potential volatility still lays. Two clans stand out as having higher levels of vote switching, these being the Proud and Patriotic State (PPS) and the Modern Working Life (MWL) clans – the latter being more likely to believe in individual responsibility for financial well-being but liberal on social issues and the environment. Nonetheless, the two groups are very different in their behaviour. The PPS were the clan most likely to have voted UKIP in 2015 (1 in 5); there was therefore a substantial proportion of this clan ‘up for grabs’ by the major parties as UKIP collapsed in 2017. By contrast, the MWL clan did not have a particularly large share for UKIP (or any other minor party) in 2015. Around half this group voted Conservative in 2015, a further quarter voted Labour, and around 1 in 8 voted for the Liberal Democrats. As a result of these very different profiles in 2015, switching in these two clans is different too. For the PPS group this is primarily switching from UKIP to one of the main parties, while among the MWL 1 in 10 switched directly between Labour and the Conservatives, such that in 2017 Labour had a very slight lead among this group.

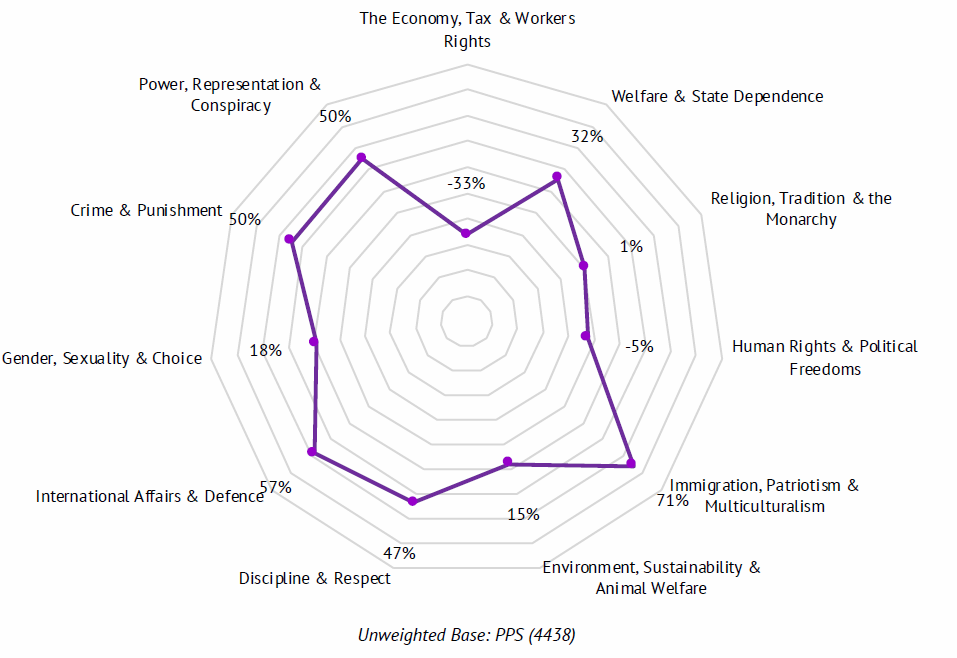

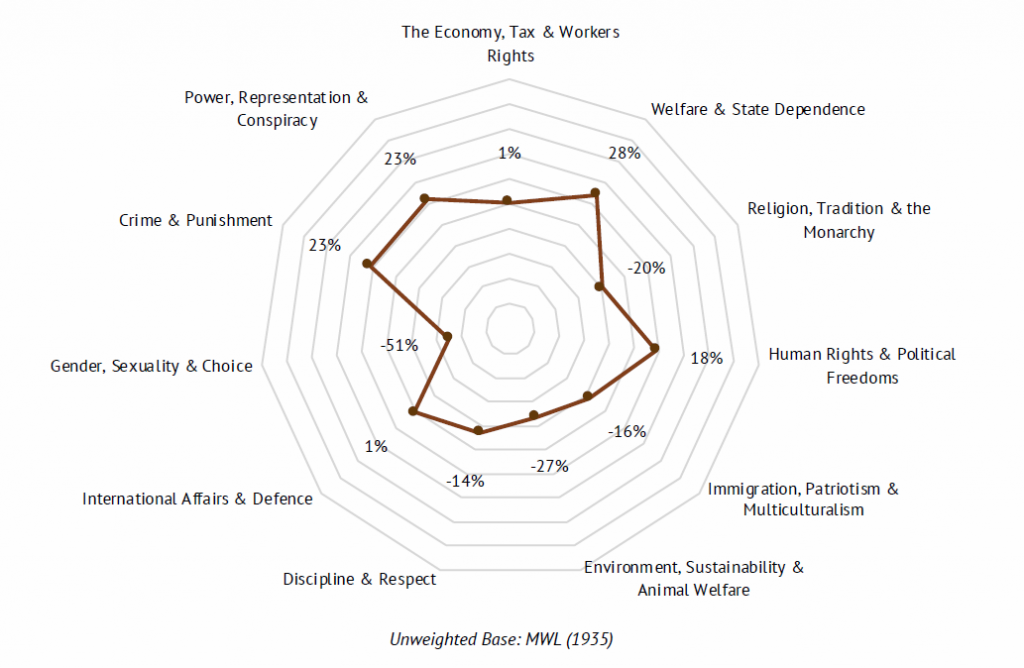

Looking more closely at the values of these two groups provides us with further clues as to how values influence political behaviour. The clans are described according to their positions on a set of 27 items which can be further grouped into 11 broader categories. Spider diagrams then illustrate the values profiles of the clans. The diagrams are drawn so that positions close to the centre of the ‘web’ are the most ‘left’ or ‘liberal’ positions and those furthest out are the least liberal or most right-wing positions.

The spider diagram for the Proud and Patriotic State group shows a values profile that lies close to the outside of the web on a wide range of issues; notably Immigration and Multiculturalism, International Affairs, and Crime and Punishment but who also have notably ‘left’ leaning views on the Economy and Workers’ Rights. In an earlier piece we described this as one of the ‘cross-pressured’ clans for this reason.

Looking at how these voters switched between 2015 and 2017 reflects this cross-pressure. Most of the switching in this clan is between UKIP in 2015 and one of the main parties in 2017. This is not all to one party, however: a mistake often made in the run up to the 2017 election was to assume that all the ex-UKIP vote would go to the Conservatives. Among this clan those who switched from UKIP went to the Conservatives over Labour in a ratio of 2:1. So, around one third of those who switched from UKIP in this clan voted Labour in 2017. By contrast among the Bastions of Trade and Industry (BTI) group (the clan with the second highest proportion voting UKIP in 2015) those who switched from UKIP overwhelmingly supported the Conservatives in 2017 (almost 95% of the UKIP switchers went to the Conservatives).

The Modern Working Life spider diagram contrasts sharply with that of the PPS. This group are much more liberal on issues of Immigration, Gender and Sexuality, the Environment and Religion. They are close to the ‘mid-point’ on the Economy but somewhat less liberal on issues of Welfare and Crime. Having less obvious and clear ties to a party on economic grounds, this clan are a key ‘swing’ clan for the major parties. While only representing a small proportion of the electorate they are nonetheless a crucial group electorally given this heightened tendency to switch directly between the two main parties.

Aside from high levels of vote switching, these two clans share another feature. They are the two clans (apart from the Apathy group) with the lowest levels of political interest. Just 1 in 10 of these groups say they are ‘very’ interested in politics. This may mean that they are less likely to have strong attachments to parties and therefore make them more volatile, but it also means they are less easy to reach with political messages.

For future elections these groups are likely to again be volatile, but with rather different possible scenarios. The MWL group could prove central to the competition between the two main parties whilst the PPS group are the most likely source of any resurgence in the UKIP vote. In both cases the main parties will need to understand the values of these groups in order to make success appeals for their support.

_________________

About the Authors

Paula Surridge is Senior Lecturer at the University of Bristol.

Paula Surridge is Senior Lecturer at the University of Bristol.

Michael Turner is Research Director & Head of Polling at BMG Research.

Michael Turner is Research Director & Head of Polling at BMG Research.

Robert Struthers is a Senior Research Executive at BMG Research.

Robert Struthers is a Senior Research Executive at BMG Research.