Voting advice applications, like Vote Match Europe, have proliferated in the last decade, reaching more and more voters and becoming institutionalised in several European countries. But do they work in promoting informed debate, political engagement and voter turnout? According to a survey conducted after over 1 million people used Vote Match in 2010, the answer is a resounding yes: 75 per cent were more aware of the policy differences between the parties, 12 per cent changed their minds as to who to vote for, and 5 per cent said that they voted as a direct consequence of using the app. By lowering the barrier for access to political information, both about the policy differences between parties and the proximity of parties to the user’s own views, voting advice applications can be a game changer, writes Pete Mills.

Voting advice applications, like Vote Match Europe, have proliferated in the last decade, reaching more and more voters and becoming institutionalised in several European countries. But do they work in promoting informed debate, political engagement and voter turnout? According to a survey conducted after over 1 million people used Vote Match in 2010, the answer is a resounding yes: 75 per cent were more aware of the policy differences between the parties, 12 per cent changed their minds as to who to vote for, and 5 per cent said that they voted as a direct consequence of using the app. By lowering the barrier for access to political information, both about the policy differences between parties and the proximity of parties to the user’s own views, voting advice applications can be a game changer, writes Pete Mills.

Vote Match Europe launched simultaneously in 14 countries across the EU on April 28. Vote Match is a voting advice application – an online election quiz which helps users find the party that is closest to their political views, based on the issues they choose as most important. Users are presented with a number of policy statements to agree or disagree with, and their answers are compared to the answers from political parties, giving them a ranking of parties based on how far their answers align.

In the past decade, voting advice applications (VAAs) have proliferated across Europe. In some countries, VAAs have been institutionalised into the electoral process. In the Netherlands, the election campaign starts with political parties answering the leading VAA’s questions. These applications have achieved a high level of penetration among the electorate: Stemwijzer in Holland reaches up to 40% of voters, while the German Wahl-O-Mat reached more than 13 million for the 2013 federal elections. Many European VAAs enjoy public funding. In the UK, however, there has so far been limited support from the political establishment for VAAs.

VAAs are a potential treasure trove of data for academics. Some VAAs on the market ask a host of questions about demographic details, voting intention, political self-identification, perceptions of party policy positions – everything except shoe size. However, users are becoming more wary of applications obviously designed to collect data. When we built survey questions into a version of Vote Match we ran for the 2013 local elections, usage dropped off significantly compared to other versions, with users complaining they just wanted to get their results without completing a survey. VAAs which aim above all to collect research data risk losing sight of the real value of this type of application: the potential to promote informed debate, political engagement and voter turnout. The bind for designers of VAAs is that data is necessary to demonstrate the impact on turnout, but the very act of collecting the data can mute the impact.

Unlock Democracy is a campaign committed to encouraging engagement in the democratic process, so this has always been our primary goal with Vote Match. The demographic which VAAs resonate most strongly with – the young and tech-savvy – is also one with the lowest turnout rates: in the 18-24 age group, in the UK just 13% say they are certain to vote in the European elections. VAAs also fit with the increasingly individualised nature of election campaigns, with personalised advice for users.

VAAs affect voter behaviour by lowering the barrier for access to political information, both about the policy differences between parties and the proximity of parties to the user’s own views. Though VAAs are gaining traction in the US and Canada, in Europe they have been most successful in countries where proportional voting sustains a multi-party system. This aligns with the theory that VAAs help voters by offering a shortcut to understanding political choices; in a system with many parties, finding out about the policy differences between them is more demanding.

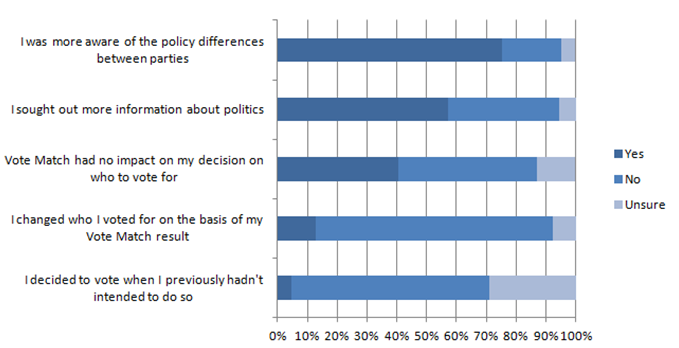

Vote Match UK is the exception: the version we ran for the 2010 election was used by over 1 million people. Our feedback survey, conducted a few weeks after the election, showed that the impact of taking Vote Match on political behaviour was significant: 75% of our users were more aware of the policy differences between the parties after using the app, 12% of users changed their minds as to who to vote for on the basis of their result, and perhaps most significantly, 5% said that they voted as a direct consequence of using the app. With the introduction of online electoral registration in the UK later this year, the transition from taking Vote Match to the next steps in political engagement will become even smoother. While there is some element of self-selection with feedback surveys, there is a growing body of evidence from countries across Europe that VAAs increase turnout among users, with reported effects as large as 15% (Netherlands) to 6% in Germany and Belgium.

Figure 1: Responses to questions after taking Vote Match (n=2250)

Turnout should not the only measure of the impact of VAAs; fostering a more informed electorate also means helping undecided voters choose between parties. One way to pinpoint the impact of VAAs on vote choice is asking users about their propensity to vote for the parties before and after receiving their results. Research from an EU-wide VAA in 2009 suggested that 8% of users switched their vote to that recommended by the VAA – much in line with the Vote Match survey. As you would expect, these switchers are not party activists cutting up their membership cards but loosely-aligned voters switching to parties who they are already considering as options. In the UK, parties are already moving to take advantage of these dynamics: the Green Party even promotes VAAs in its election material. As they grow in prominence, VAAs are likely to have effects not only on users, but on party positioning as well.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Pete Mills is Policy and Research Officer at Unlock Democracy, a campaign for democratic and constitutional reform.

Pete Mills is Policy and Research Officer at Unlock Democracy, a campaign for democratic and constitutional reform.

I don’t seen to find the app; Do you search for it just as “vote match”; is there any restriction to find it in some countries?