The Prime Minister recently vowed to remain in office if he lost the referendum on the UK’s EU membership. His comments came less than a year after he told the BBC his plan was to step down before the 2020 election. So when, if ever, should prime ministers resign and what impact does such a choice have? Kingsley Purdam, Dave Richards and Nick Turnbull write that although past resignations allowed politicians to control their legacies, the key element was that they were unexpected. In the pre-ordained case of Cameron, the announcement of a future resignation has come to define his entire term, as well as the dynamics of his leadership.

Credit: Defence Images CC BY-SA

Credit: Defence Images CC BY-SA

On either side of the Atlantic, 2016 has offered up contrasting but related events concerning the highest office of state. First, there was President Obama’s last State of the Union address, a constitutional nicety driven by the limits placed on presidential terms in the US. For Americans, this valedictory tour de force has a familiar pattern to it; an opportunity for the incumbent to survey the highlights and narrate their own legacy, so focusing America’s mind on the issue of succession.

On this side of the Atlantic, David Cameron has already opted to step down ahead of the 2020 General Election. He mused that two terms as Prime Minister were quite enough, stressing the importance of retaining his sanity. Yet in January 2016, he suggested that in the event of a ‘Brexit’, he would seek to remain in office for a full term.

So what can we learn about leadership from leaders who resigned their roles when they could have stayed on? What is the optimum time for being a political leader? Looking back to 1976, Harold Wilson resigned as Prime Minister, an event that Tony Benn claimed in his diary ‘…nobody knew was coming’. This may not strictly be true, certainly Bernard Donoughue and others in Wilson’s inner-circle were wise prior to the event. What was notable about the Wilson resignation was that of a Prime Minister leaving office ostensibly on his own terms and timing.

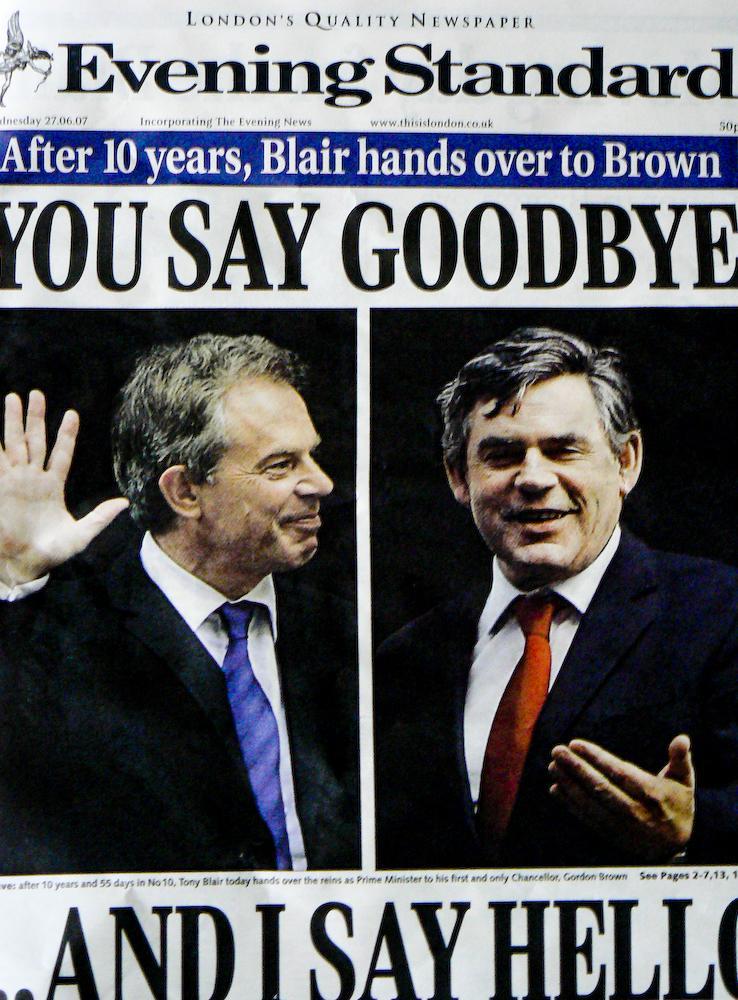

Fast-forward three decades and the same cannot be said of the resignation of Tony Blair. Here also was a Labour Prime Minister whose departure was not fore-shadowed by the end-game of an electoral cycle. From the so-called ‘Granita pact’ onwards, the clock on Blair’s incumbency was always ticking to a time not of his making. This proved to be the case when, despite declaring he would serve out a full term after his historic third electoral victory in 2005, by the summer of 2006 the first informal coup against Blair had taken place and twelve months later he was gone. Blair, unlike Wilson was never master of his own prime ministerial destiny, dependent instead on the contingency (regarding instability) of the ‘Brown’ faction within the Parliamentary Labour Party. His legacy has since been widely questioned, though notably not by anyone who has attained any measure of success by doing so. Brown resigned as an election loser, so to Ed Miliband. As for Jeremy Corbyn…

If the lessons offered by Wilson and Blair are the need to hold cards tightly to one’s chest while avoiding Faustian-bargains at all costs, David Cameron appears not to have heeded them. Cameron’s current position brings to the fore a number of questions surrounding the office of the Prime Minister and about political leadership in general. When should a leader resign? What constitutes a resigning failure? Can leaders control their legacy by resigning at a good time?

From the moment Cameron unwittingly let slip his infamous quip ‘terms are like Shredded Wheat – two are wonderful but three might just be too many’, his ability to navigate the terms of his own resignation were compromised. The question of resignation has increasingly come to define him, his possible successes and failures, his conduct, and his legacy. In effect, by pre-announcing his resignation he has created a problem similar to that experienced by second term US presidents. A kind of lame duck Prime Minister. A cuckoo in the nest.

Events of course can also come into play. With the forthcoming referendum, commentators have worked on the assumption that a ‘Leave’ vote would almost immediately be followed by Cameron’s resignation. Yet, the Prime Minister has suddenly announced that he intends to ‘stay-on’, even if he lost the vote on ‘staying in a reformed Europe’. There is an irony here that is hard to ignore: having fired his own starter pistol on a long, drawn out and potentially, politically damaging race for the leadership of the party, Cameron is at the same time refuting the notion that the loss of a national referendum would not render his own position as Prime Minister untenable. This suggests Cameron’s musings on his capacity to control the destiny of his own incumbency are somewhat lacking in reflexivity.

It is at this point that we might turn to the resignation of Margaret Thatcher and the lessons offered from those historic events back in November 1990. The most insightful academic account explaining Thatcher’s fall from office is offered by Martin Smith and his adaptation of the power-dependence model originally developed by Rod Rhodes:

An explanatory model of prime ministerial power needs a number of elements: a recognition that the power of the Prime Minister is variable and therefore power within the core executive depends on context; a view that prime ministerial power depends on institutional resources as well as individual attributes; a definition of power as relational; and an acceptance that power is dependent on interaction rather than command. There is mutual dependence within the core executive.

Credit: Number 10 CC BY-NC-ND

Credit: Number 10 CC BY-NC-ND

In Thatcher’s case, the combination of hubris and weariness with the Westminster game led to her failing to maintain crucial lines of dependence with key cabinet colleagues in the core executive. The result was that her position was fatally undermined as events took over. Smith reminds us that this model:

…recognizes that power does not belong to the Prime Minister, nor is it an attribute of an institution. Instead ministers and the Prime Minister have resources. Power is their capacity to use these resources, but the use of resources is dependent on the particular circumstances of any situation…Power is relational and not a zero sum.

For Cameron, as with Blair, the knowledge that the end is pre-ordained, makes the nurturing of those crucial lines of dependence increasingly hard to sustain. Loyalty within both the Cabinet and the wider Parliamentary Party is already ebbing elsewhere. If one then throws into the mix major contextual factors, including potential defeat in the EU referendum, such a combination is undoubtedly toxic for Cameron’s leadership.

Perhaps voluntarily choosing to give up the highest office of state tells us something not only about Cameron as a person, but also of the nature of public office in the twenty-first century. It may be that Cameron wants to spend more time with his family, or he feels he has done what he can. He was of course one of the youngest leaders of the Conservative Party and the youngest British Prime Minster in nearly two centuries. Even if Cameron does not have a private agreement with George Osborne (who reportedly quipped that he had never been to the Granita restaurant), it would be churlish to deny he does not possess some sense of obligation over the succession. Perhaps just the restaurant has changed, although, Cameron has been careful to regularly name-check other possible suitors when the opportunity has presented itself.

Even at the height of her greatest wobbles – be it the Westland Crisis or the Poll Tax – it is hard to imagine Thatcher entertaining the thought that it might be time for a ‘fresh pair of eyes and fresh leadership’. Yet this is exactly what Cameron has done. Perhaps Cameron’s idea of leadership is handing over to someone very similar – in all senses of the word – to himself. Whether or not events allow him to bow out at a time of his own choosing, what follows within the British tradition will be a swift, potentially brutal, goodbye and hand-over, as his most recent predecessor Gordon Brown discovered. And like President Obama, Cameron will be one of the youngest retired leaders.

___

Note: a version of this article also appears on the PSA Parliaments and Legislatures blog.

About the Authors

Kingsley Purdham is Senior Lecturer in the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research, University of Manchester.

Kingsley Purdham is Senior Lecturer in the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research, University of Manchester.

Dave Richards is Professor of Public Policy at the University of Manchester.

Dave Richards is Professor of Public Policy at the University of Manchester.

Nick Turnbull is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Manchester.

Nick Turnbull is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Manchester.

It is not their fault as the authors are too young to know but Wilson stepped down because he had early onset Alzheimer’s, something which eventually claimed the mind of Thatcher too.

Wilson may have also had psychiatric problems brought on by apparent attempts by a cabal of newspaper owners and military personnel to stage an apparent coup d’état .

In the case of Cameron, his remarks about standing down have to be considered within the actual context within which they were said.

He said them because he thought he might lose the 2015 general election and this was his way of attempting to reassure voters that he was not power-crazy.

He was as surprised to learn his party had won a majority in 2015 as anyone else.

Remember?

As for Blair standing down – who knows?

No one yet has provided a sensible explanation.