Mainstream parties need to begin addressing conservative whites’ anxieties about the demographic growth of Islam, or populists will continue to thrive, writes Eric Kaufmann. He explains that this demands a sustained programme to improve demographic literacy.

Mainstream parties need to begin addressing conservative whites’ anxieties about the demographic growth of Islam, or populists will continue to thrive, writes Eric Kaufmann. He explains that this demands a sustained programme to improve demographic literacy.

Geert Wilders may not have come first in the Dutch election, but he came second and forced his opponent, Mark Rutte, to tack closer to Wilders’ Muslim-bashing position. Once again, the pundits will wring their hands and tell themselves the comforting story that economic policy can undercut support for right-wing populism. But, as with the Brexit and Trump vote, ethnic change and values, not economics, better accounts for populist success.

Why Muslims matter

The Muslim share of the population, and its rate of increase, is an important barometer of cultural change. Raw immigration inflows aren’t a good measure since they contain a large share of intra-European migrants – often from neighbouring countries – who evince little concern in most mainland EU countries. Muslims are not only culturally different to Europe’s white majorities, but – because our brains are drawn to vivid images rather than representative data – evoke panic about terrorism and threats to liberty.

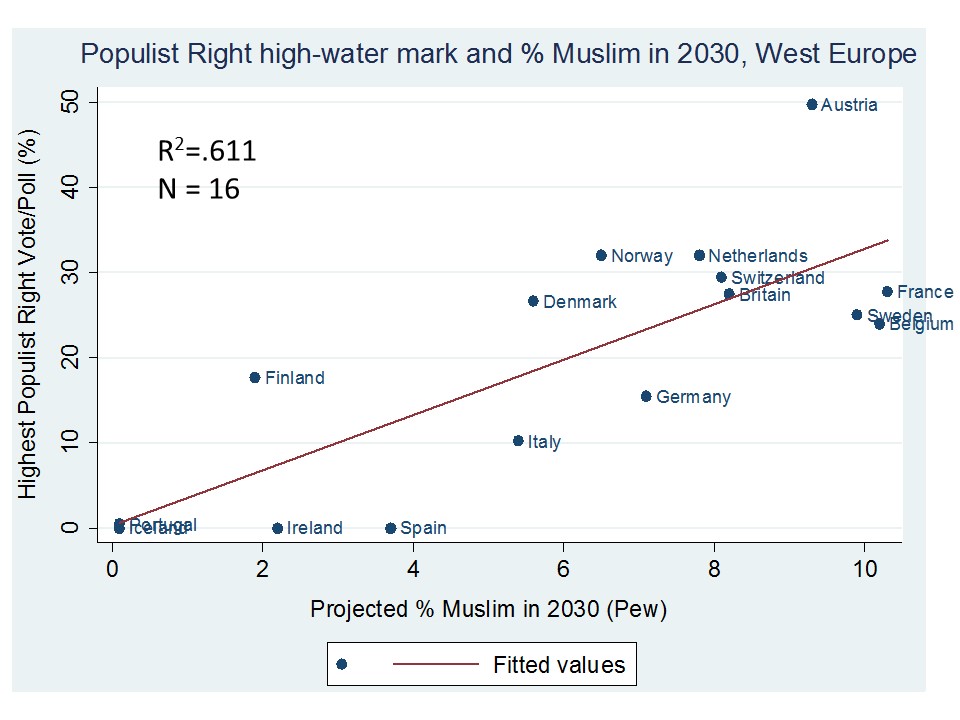

Figure 1 shows an important relationship between projected Muslim population share in 2030 and support for the populist right across 16 countries in Western Europe. Having worked with IIASA World Population Program researchers who generated cohort-component projections of Europe’s Muslim population for Pew in 2011, I am confident their projections are the most accurate and rigorous available. I put this together with election and polling data for the main West European populist right parties using the highest vote share or polling result I could find. Note the striking 78 percent correlation (R2 of .61) between projected Muslim share in 2030, a measure of both the level and rate of change of the Muslim population, and the best national result each country’s populist right has attained.

Figure 1.

Source: Election and poll data and Pew Forum, ‘The Future of the Global Muslim Population,’ interactive feature. Accessed Mar. 10, 2017.

Source: Election and poll data and Pew Forum, ‘The Future of the Global Muslim Population,’ interactive feature. Accessed Mar. 10, 2017.

Clearly, other factors matter: Austria’s Freedom Party nearly won the election in 2016 when Norbert Höfer captured 49.7 per cent of the vote. This places the party well above the line of what we would expect on the basis of its 2030 Muslim population. Likewise, Germany’s AfD or the Sweden Democrats underperform the regression line. The Front National’s maximum poll of 28 per cent is also below what we expect, though this could increase to around 40 per cent if Marine Le Pen advances to the second round in France’s upcoming election.

Why focus only on Western Europe? Because right-wing populism in established democracies differs in important ways from similar phenomena in the new democracies of the continent’s East. There are two main types of nationalism: one focused on national status, pride and humiliation; the other on ensuring the alignment of politics and culture. East Europe’s nationalism is more concerned with the former, West European nationalism with the latter. In addition, memories of an authoritarian golden age are fresher in the post-Communist world, where they continue to inspire revanchism. In western Europe, appeals to the halcyon days before messy democracy ruined everything carry little resonance.

Why use maximum populist right share? Because support for populist right parties is highly volatile over time whereas Muslim share is not. Any cross-country comparison using current polling data will therefore be noisy and inaccurate. Lacking an established brand, populist right parties are more vulnerable to leadership change, scandal, and splits than mainstream parties. Their high-water mark is therefore the best indicator of their potential support in a country’s population. That is, the extent to which those who support populist right aims are willing to defy anti-racist norms to vote for them.

As with Brexit and Trump, education, and not income, is the critical demographic. This is because values rather than people’s economic situation are critical to explaining the vote. And this change tends to polarize populations – radicalizing so-called ‘authoritarians’ who prefer safety and security to novelty and change.

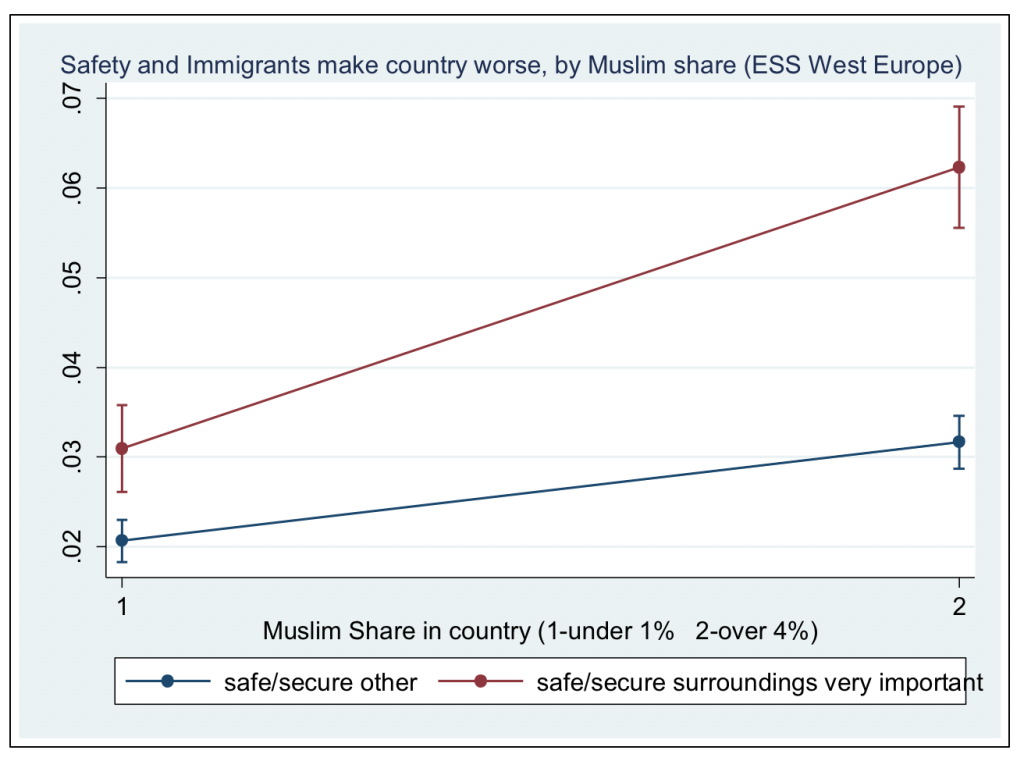

Immigration attitudes are tightly linked to populist right support. With this in mind, consider the relationship between authoritarianism and immigration attitudes in figure 2, based on data for 16,000 native-born white respondents to the 2014 European Social Survey. ‘

Figure 2.

Source: Data from European Social Survey 2014. N=16,029. Pseudo R2= .084. Controls for country income; also individual income, education and age. Countries: Austria, Belgium, Switzerland, Denmark, Germany, Finland, France, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway and Sweden.

Source: Data from European Social Survey 2014. N=16,029. Pseudo R2= .084. Controls for country income; also individual income, education and age. Countries: Austria, Belgium, Switzerland, Denmark, Germany, Finland, France, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway and Sweden.

Authoritarians’ – those who place a high value on safe and secure surroundings, are more likely to perceive immigrants as making their countries a worse place to live. But in countries with low Muslim populations (i.e. Ireland or Finland, where Muslims are less than 1 per cent), authoritarians and others differ by only one percentage point: 3 per cent of those who say safety and security are important ‘strongly agree’ that immigrants make their country worse compared to 2 per cent for others.

Now look at the rest of the sample, from countries where Muslims exceed 4 percent of the population. The gap between the red and blue lines is now three times as large, with over 6 per cent of safety-conscious individuals now strongly anti-immigrant. If you are white and less concerned about safe and secure surroundings, the share of Muslims in your country has only a small impact on your view of immigrants. If you care about safety and security, Muslim share makes a big difference to those views.

This is no artefact of Irish and Finnish uniqueness: an interaction of Muslim share and safety/security across the full range of Muslim share and the security scale produces an even stronger effect. This tells us that ethnoreligious change interacts with authoritarian values to ramp up concern about immigration – which benefits the populist right.

Policy implications

What to do? To begin with, mainstream parties and the media need to acknowledge that demographic change increases anxiety over immigration among whites whose values are oriented toward security and order. Having isolated the real issue, they must then focus their efforts on raising people’s awareness about the realities – not the fantasies – of Muslim demography in their countries. This will be much more effective than decrying worries as racist – which will only amplify fears that people are not being told the truth.

The belief that Muslims have sky-high fertility and will take over Europe is not confined to viral videos with over 16m views. At the European Commission, I was astounded to hear a member of the European elite ask whether such claims were true. The extent of this demographic illiteracy makes it imperative to begin a concerted public information campaign.

Figure 1 shows that no country will be more than 10 percent Muslim in 2030. So in 2050, France is projected to be just 10.4 percent Muslim. Yet Ipsos-Mori’s report shows the average French person thinks France will be 40 percent Muslim in 2020, instead of the actual 8 percent. Across Europe, the average overestimate of 2020 Muslim share is 25 points. Previous work by Bobby Duffy and Tom Frere-Smith at Ipsos-Mori shows that people across the West routinely overestimate immigrant share by a factor of two or three.

But information can counteract these claims. A recent survey experiment finds that when people are given accurate information about the share of foreign born in their country then asked a month later what the share is, they adjust their estimates 12 points closer to reality. The Pew projections, based on the best immigration, fertility, and switching data we have, show that the rate of Muslim growth in Europe is tapering. In 2050, no West European country will be more than 12.4 per cent Muslim, far lower than most think is the case today.

Europeans should also be regularly told about what is happening with Muslim total fertility rates (TFR). These have dropped across much of the Muslim world. Among leading European source countries, many are at or below replacement. Turkey’s is 2.06 (births per woman), Iran’s 1.92 and Morocco’s 2.12. Across Europe, the Muslim TFR is 2.1, precisely the replacement level. Finally, how many French voters are aware that half of Algerian-origin men marry out, or that 60 percent of French people with one or more Algerian-origin parents say they have no religious affiliation?

Europe’s opinion formers have gushed about transformative diversity so much that people now believe it. My previous work on conservative White British voters shows that demographic reassurance, focusing on the idea that immigration can be absorbed with minimal change, significantly reduces anxiety about immigration and support for Hard Brexit. Europe’s mainstream parties and the media need to stop skirting public anxieties and start addressing the mammoth problem of demographic illiteracy.

_____

Eric Kaufmann (@epkaufm) is Professor of Politics at Birkbeck College. He is currently writing a book about the White majority response to ethnic change in the West (Penguin).

Eric Kaufmann (@epkaufm) is Professor of Politics at Birkbeck College. He is currently writing a book about the White majority response to ethnic change in the West (Penguin).

Hi Eric. Great piece. Just wanted to get your thoughts on the effects of external factors, such as illegal immigration and asylum. If we assume that illegal migration and asylum claims will only go up (given the likely chance of the second round of the Arab spring, more conflict in Africa, and climate-migration which will be of a monumental scale), then surely Europe will become totally islamized within this century? Thanks.

You’ve missed one contributory factor: the utter willingness of those on the left to actively promote the destruction of their own civilization. That has to be the final determining factor.

Hi Eric, I made a couple of comments on this but it looks like you deleted them. I’m not sure if that was because you felt they were inflammatory or because they went into spam? I always try to be civil when commenting on potentially emotive topics so I apologise if they caused upset, that was certainly not my intention. I was trying to give you my thoughts directly related to your post. Regards, Ian.

“He explains that this demands a sustained programme to improve demographic literacy.”

This won’t work. Because this will feel like it’s being ‘forced’ on the people. I.e. like at present how the media doesn’t report on attackers, or it doesn’t disclose all information. It makes people lose trust in mainstream media, so they seek information from alternative media. The government instead needs to stop Sharia Law (which is arguably one of (if not the) biggest fears among these voters), or traditional establishment parties will continue to be hollowed out. This is one of the big factors, not the only one of course. The sharia law problem also goes back to traditional conservative values around equality of opportunity, not equality of outcomes (which is what the left push, hence why many voters see the Left as being facilitators in this). They want and expect equal treatment to all and for all to abide by the same rule of law and values / general culture. Not equality of outcomes, i.e. positive discrimination. They see this as hypocrisy. They have been under austerity, minimal wage growth, stagnant middle class, rising living costs (housing, education, cost of raising a child all up), and then they see people come in invited by the government who get free handouts (their taxpayers money). The economics side of the argument is a failure from the governments perspective. Since they could have in reality housed these migrants in refugee camps via direct foreign investment in a magnitude higher than what they cost in Europe (i.e. Sweden housed 3000 refugees in tents at the cost of housing 100,000 in the middle east – data taken from Swedish PhD economist)). Looking at the equality of opportunity vs outcomes, this is just basic conservativism. So they will forever oppose equality of outcomes, what they perceive as special treatment for Muslims or other groups over them, and will continue to vote accordingly. Many other complexities. The point being trying to get involved in a statistics battle with them won’t work, they have many statistics also that work in their favour. The only way to genuinely calm them down, is to offer them their conservative solutions as said above. Ban sharia law. No opportunity of outcomes. No special treatment. Integration. And a strong border to calm their fears of new waves coming (i.e. see Turkey at present, and intelligence reports of future waves, and Africa’s population boom, etc). These people can read information, and do read it from alternative media. You can’t treat them as idiots, or it will backfire.

“they must then focus their efforts on raising people’s awareness about the realities – not the fantasies – of Muslim demography in their countries”

This: https://www.samaa.tv/international/2017/03/have-5-kids-not-3-erdogan-tells-turks-in-europe/

Ahem…and you were saying again?

> In 2050, no West European country will be more than 12.4 per cent Muslim

Well, presumably that is the result of the medium model. What does the high model say? Are we assigning 0% probability to the high model?

Also, I would be interested to see figures for ethnically non-european non-whites as a whole. I have seen predictions from, e.g. Migration Observatory, that non-whites will be a minority by 2066 in the UK.

Some answers to your questions (the best I can!):

Noah, you’re right, R2 of .61 means correlation of .78. So will change that.

On projections – even in 2050, Sweden is projected to be highest at 12.4 pc Muslim. So the situation is not really so different in the young population.

The question of white decline is not the same as Muslim increase as the nonwhite, non-Muslim share may rise.

My point on absorption is that where it is happening successfully, it should be highlighted – and that societal narrative in the media should tone down the ‘we’re becoming so diverse’ message.

Finally, I didn’t suggest that this data supports any particular immigration policy.

Further comments:

1) On projections: In the case of Greece, where the (increased) migrant/refugee inflow is overwhelmingly Muslim and is coupled with low birth-rate of the natives, what projections do you have? The ones I have available indicate that by 2060 the migrant population will constitute 31.8% of the 0-14 year-olds (but only 9% of the 65+)

2) On absorption: Do you have a single case of European country where the current levels of immigrant inflow (especially from Muslim countries) are being successfully absorbed by the native population?

3) On immigration policy: the basic message of your article is that Europeans’ anxieties over Islam’s demographic growth are owed to misinformation and “demographic illiteracy”. Thus, in your view, the essence of the issue is not one of actual demographics (declining birth-rates, increased migrant inflow) but of “accurate” information. Consequently, there is no flaw in current immigration policies (and thus there is no need to change them). Just to inform the “misinformed”!

Noah, you are correct. .78 it is, my brain was switched off. Second point still stands though.

1) The author’s suggested remedy of improving demographic literacy is totally irrelevant. Support for anti-immigration parties is not driven by the size of Muslim population, not by the perceived size of the population, but by the (perceived) rate of undesirable behaviour by Muslims. Currently Britons are under the impression that 20%, or thereabouts, of the population is responsible for 90% of all sexual sex trafficking (based on convictions, which given the evidence of sustained mass cover ups certainly understates matters). If they were re-educated they would realise that …. 5% of the population is responsible for 90%+ of all child sex trafficking. The same goes for terrorism in France or sexual assault in Germany and Sweden.

2) The fact that population in the Middle East has ceased expanding is not pertinent to the question of whether Whites will become a minority. The population of Africa is expanding and will hit 4 billion by the end of the century. There is no shortage of people. Either immigration is stopped or whites will become a minority. In the US Whites are already a minority of primary-school children. If you believe that this is good thing, or a neutral thing, then you are entitled to argue for that position, but you should do so honestly. If your case is that Europe will end up looking more like Somalia and Eritrea than Morocco or Turkey, I suggest you might have to try a bit harder.

If the r-squared for the chart is .61, then the correlation is .78.

Interesting piece but the analysis should go even deeper in my opinion. More specifically:

1) The rate of increase for the Muslim population and its projections should take into account: a) legal migration flows, b) illegal migration flows, c) refugees and d) fertility rates

2) Population projections should not only offer a short-term picture (i.e. 2030 which is just 13 years from now), but also include scenarios for 2050 and 2080 so as to have a longer-term picture of the current trends

3) The population projection results should also be broken down to age groups (i.e. 0-10, 11-17, 18-24, 25-34 etc) so as to demonstrate the impact not only in the total population but also among younger and older age groups. The picture in the younger age groups represents more accurately the shape of things to come

4) The analysis should also be complemented with social research data on immigrant integration in European communities. If integration is already problematic, why shouldn’t immigration be slowed down?

5) The fertility rates of Muslim countries should also be complemented by estimations of those countries’ population (in absolute numbers) who are seriously considering migrating to Europe (either legally or illegally)

6) I think the author’s statement that “immigration can be absorbed with minimal change” is wishful thinking considering the already-existing fragmentation and alienation between native and migrant populations in European countries

Overall: In order to deal with the issue of immigration, acknowledging the anxieties of Europe’s native populations is a good start but it should lead to actual change in the current immigration policies and not to a mere window-dressing and repackaging of the same – failed – policies! Migration policy should become much more restrictive and selective.

Thanks for a really interesting article.

(1) You assume that if people overestimate the Muslim proportion of the population, they’ll be more anti-Muslim in attitude. You’re probably right, but I can think of one objection to that reasoning.

People massively overestimate the gay proportion of the population. According to Gallup, most Americans guess that around 1 in 4 people are gay, when the actual figure is less than 1 in 25. It seems this false estimation actually makes people more tolerant of gays; denying 25% of the population the right to marry feels more unjust than denying 4% that right, even that doesn’t really make sense as a philosophical argument.

(2) When we find that people make wrong guesses about social statistics, it’s always worth asking why. For instance, are they confusing the size of the foreign-born population with that of the non-white population? When people see a dark-skinned woman in Islamic clothing pushing a stroller, they may assume that both mother and children are immigrants, but it’s actually very unlikely the children are. They’ve made a mistake, but not necessarily a paranoid or malevolent one.

Another possibility is age effects. The Muslim population is relatively young. So someone who works as a school dinner server in inner London may massively overestimate the Muslim proportion of the population, while someone who works in a retirement home in Cornwall may underestimate it. Maybe researchers should ask more detailed questions, e.g. “What proportion of the school age population have Muslim parents?”.

(3) I thought France banned the collection of statistics measuring religion or ethnicity.

Looks like I introduced my own typo. Should of course be square root of 0.61.

There’s a small typo relating to Figure 1. The correlation is not 0.61, it is 0.37 ie the square root of 0.37. For macro data that’s far from striking.

Secondly, you could interpret Figure 1 in another way. There are two groups of countries. In group 1 there are no electorally viable populist right wing parties (Portugal, Iceland, Ireland, Spain) and the proportion of Muslims makes not difference (obviously). There is a second set of countries where there are electorally viable populist right wing parties and the proportion of Muslims makes little difference to the % of the vote they get (possibly none at all if you use the vote for the Austrian legislature rather than the Presidential run off).

In other words the regression slope is driven by the extremes at the top and the bottom.

Anyone would think that the worries that the muslims will create caliphates on the european mainland are based on the the way the muslims behave in the middle east, it isn’t populist or populism to have genuine rational fears, in fact if the PC brigade opened their eyes to reality they wouldn’t make such crass claims in the first place. It isn’t the unelected elite on the commission who will bear the brunt of a sociological eruption it is the average joe walking down the street.

“… it isn’t populist or populism to have genuine rational fears, in fact if the PC brigade opened their eyes to reality they wouldn’t make such crass claims in the first place….”

Very true. Concerns about the consequences of harbouring a significant population adhering to islam within one’s country have a clear foundation in evidence from throughout the history of this peculiar and archaic ideology. The ‘islamic world’ has never followed the trajectory of other population groups in terms of political, cultural, or social evolution and there is no evidence to suggest this will change anytime soon.