Joblessness among the UK’s younger generation is currently at very high levels, but the rise in youth unemployment began in 2004, well before the onset of recession. Barbara Petrongolo and John Van Reenen consider potential explanations.

Joblessness among the UK’s younger generation is currently at very high levels, but the rise in youth unemployment began in 2004, well before the onset of recession. Barbara Petrongolo and John Van Reenen consider potential explanations.

The UK economy has experienced the worst recession since the war in terms of loss of output, yet the overall unemployment rate is 8%, lower than the peak of the 1980s and 1990s recessions. Youth unemployment, however, has risen dramatically, and because of the ‘scarring’ effects of joblessness on an individual’s later life, has become a key policy concern. But to tackle the problem, it is important to understand how youth unemployment typically responds to a cyclical downturn and why, this time, it started to rise well before the recession began.

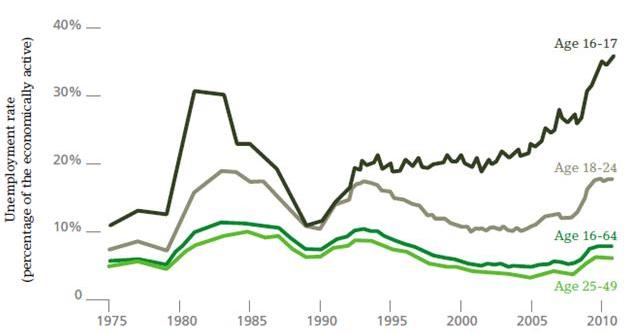

Figure 1: Unemployment rates by age group, 1975-2010

Source: Labour Force Survey (annual data 1975-91, quarterly data 1992-2010)

Figure 1 shows the unemployment rates for the working age population (people aged 16 to 64) and for three subgroups – prime age (25-49), young (18-24) and teenagers (16-17). The prime age group follows the general pattern of the aggregate labour market, but it is clear that the young are much more sensitive to the state of the business cycle. The unemployment rate is higher for the younger groups and the magnitude of this disadvantage widens during a recession.

This is unsurprising as employers will be reluctant to lose more experienced workers who have firm-specific skills and greater redundancy costs. So the burden of adjustment typically falls on low-wage workers such as young people. Minorities and the less educated also tend to fare worse during downturns.

The fact that teenagers do not appear to have experienced the same fall in unemployment after the 1990s recession as older groups can be explained by important concealed ‘selection effects’ as increasing numbers of teenagers without jobs stay in education. Indeed, if instead of focusing on unemployment figures we use information on the proportion of young people who are ‘not in employment, education or training’ (NEETs), the trend for 18-24 year olds is very similar to the trend in unemployment, while there has been a decline in the 16-17 year olds NEET rate.

Figure 1 shows that the unemployment rate for the young has increased by more (in absolute terms) than the unemployment rate for older groups since the onset of the recession. Moreover, there has been a significant fall in hours worked by young people compared with older groups, while wages have flattened or fallen for younger workers. Both of these facts indicate that young people are faring worse during the downturn than other groups.

However, the data do not suggest that there is a special problem of youth unemployment in this recession compared with past experience. The fact that young people suffer more during downturns is quite consistent with what has happened in previous recessions in the UK and elsewhere. A bigger problem is what was happening before the recession.

Figure 1 shows that prime age unemployment has been falling dramatically since the early 1990s, and then rose again in 2008. Youth unemployment had also been falling since the early 1990s, and by 2004 it had dropped to about 9%, below its 1989 level. But then it started rising in 2004, several years in advance of the recession.

So there seems to be a component of the differential between adult and youth unemployment that is not explained purely by the stronger impact of cyclical downturns on young people. Despite several forces that may be related to the poor performance of the youth labour market in recent years, the bulk of the rise in youth unemployment in the period 2004-08 remains largely unexplained. What might be behind this increase? We look at six possible culprits.

Rising migration

The UK has experienced a record increase in immigration in the past few years. The proportion of foreign-born population was below 6% in the early 1990s, but is currently about 10%. In London, this proportion rose from 28% to the current level of around 40%. Those immigrants who are less skilled than natives will be closer substitutes for inexperienced young people and may hurt young people more than adults.

Some simple evidence on this can be provided by looking at the correlation between youth unemployment and the migration rate across UK regions over time, controlling for the business cycle. Evidence shows that a one percentage point increase in the proportion of foreign-born in the working age population is associated with an increase in youth unemployment of 0.43 percentage points, holding the state of the business cycle constant.

So it might be concluded that foreign migration harms the job prospects of young people. But this result is largely driven by differences between London and the rest of the country, as the capital experienced particularly high rates of immigration and a relatively higher increase in unemployment. Excluding London from the sample, the correlation between youth unemployment and the migration rate is basically zero. There is no compelling evidence of a strong causal impact of higher migration on youth unemployment.

The minimum wage

Is the National Minimum Wage another cause of increased youth unemployment? Although its extension in October 2004 to cover 16-17 year olds who are not apprentices did coincide with a strong increase in their unemployment rate, research has generally found few effects of the wage floor on jobs. For example, the 2003 increase in the minimum wage had insignificant employment effects for all demographic groups including young people.

Furthermore, if minimum wages were to blame, we would expect a positive jobs effect on teenage apprentices, who were exempt from the 2004 legislation. In fact the job rates of 16-17 year olds fell from 15% in early 2003 to 13% in early 2007, casting doubt on the minimum wage explanation.

Changing structure of welfare-to-work benefits

The poor showing of the youth labour market since 2004 is particularly disappointing given the considerable policy reform to the Employment Service (especially for young people) in the last two decades. Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) was introduced in 1996 as the main form of unemployment benefit and greatly increased the job search requirements for receiving benefits. Although it appeared to reduce the claimant count, few of those leaving seemed to find sustainable jobs.

The second policy, the New Deal for Young People, was introduced in 1998 with the aim of improving the incentives for young workers to find jobs. All 18-24 year olds on JSA for six months received help with job search from a dedicated personal adviser. So there was some ‘carrot’ of job search assistance as well as a tougher ‘stick’ of stricter monitoring. This seemed to be successful, rigorous evaluations showing that job finding rates increased by about 20% as a result of the policy.

But this success was possibly undermined when around 2004, the Employment Service was given incentives to focus less on young people on JSA and relatively more on other groups, such as lone parents and those on incapacity benefits. Although there is no rigorous evaluation of this change, the timing does suggest that this may have been a cause of the rise in youth unemployment before the recession.

A further problem is that the increasing numbers of Labour Force Survey unemployed who are not claiming JSA separate them from any direct effect of the New Deal and the Employment Service in general. There is no way for the state to give direct help to young unemployed people who have little contact with the job finding agencies.

Education and school-to work transitions

Another possible explanation is that the quality of education for the type of young people likely to be unemployed may have declined. Although standards as a whole appear to be rising, it is possible that targets have led schools to neglect some of the ‘hard to reach’, who may end up unemployed. For example, an evaluation of the Excellence in Cities programme in disadvantaged areas finds that the policy had a relatively high impact on high ability pupils in poor schools, but it did not help low ability pupils, who may have higher unemployment risk in the future.

Similarly, the publication of league tables gives schools incentives to focus on pupils at the margin of achieving the headline indicator (the percentage with five or more A*-Cs at GCSE) but few incentives to focus on those near the bottom of the distribution. It is thus important that education policies do not neglect the bottom of the ability distribution, which is often hard to reach. More generally, improving the careers guidance service for school leavers could be a way of improving the position of young people.

Conclusions

The UK labour market has held up relatively well so far, given the depth of the latest recession. Young people, however, have fared much worse than other groups with larger increases in unemployment and bigger falls in hours and wages. Unfortunately, this is to be expected as young people always suffer worst during downturns.

More puzzling, however, is the fact that youth unemployment and NEET rates were already bad going into the recession, having been rising since 2004. The evidence gathered to date does not provide a firm answer to why, after over a decade of steady improvement, youth unemployment started rising in the mid-2000s.

With youth unemployment currently around 18%, policy actions will be key to reducing the threat of large numbers of young people facing long-term unemployment and the lifetime scars that leaves. In particular, it is important to maintain strong welfare-to-work policies that keep young people attached to the labour market, and to ease the transition from school to work with apprenticeship programmes targeted at low-achieving groups that are typically ‘harder to reach’. But there is no evidence that caps on immigrant flows or a reduction in the minimum wage would have a strong bite on the youth labour market.

The full version of this article first featured in CentrePiece magazine Volume 16, Issue 1, Summer 2011, which is now online.