If only all our world’s misunderstandings

were blessed by Rama,

and our failed loves could begin, with stars in their eyes, again

Daljit Nagra, ‘Ramayana: A Retelling’

Lexi Aisbitt marks Diwali by considering how South Asian religious festivals are observed in Britain, and the nostalgic significance of celebrations.

Lexi Aisbitt marks Diwali by considering how South Asian religious festivals are observed in Britain, and the nostalgic significance of celebrations.

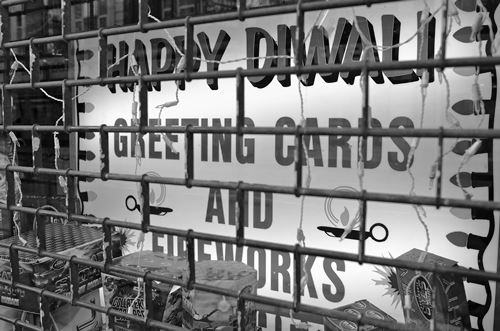

Today it is Diwali. Across India, and among the South Asian diaspora around the world, the festival of lights will be celebrated in a variety of different fashions. Houses will be cleaned, candles and lamps lit, new clothes donned and admired, Lakshmi pujas performed and large quantities of snacks and sweets prepared and eaten amongst family and friends. This evening, the skies over London will explode in showers of fireworks, a fitting prelude to the Guy Fawkes celebrations occurring in two weeks’ time.

In lots of ways Diwali is a festival of returns. Many Hindus understand the celebration as marking the return of Rama and his wife Sita and brother Lakshmana from exile, as told in the epic of the Ramayana. For Sikhs, the date signifies the release of the sixth Guru from Mughal imprisonment, along with 52 other princes holding on to his specially constructed coat tails, and his return along a lamp lit paths to Amritsar. But what of celebrations for South Asians in London who will not return home for Diwali, or for whom home lies within the M25?

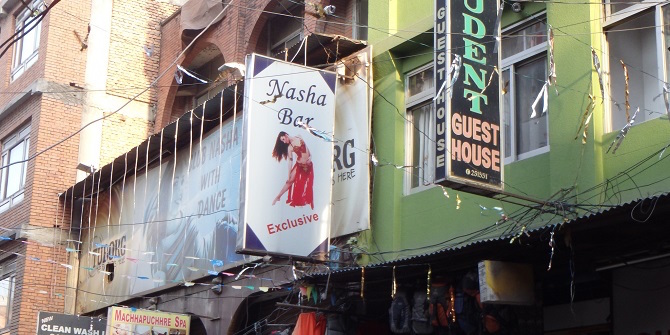

Earlier in the week walking down the streets of Southall, home to London’s largest South Asian community, preparations were in evidence. Shopkeepers cradling mugs of builders’ tea peered out from their doorsteps surrounded by garlands of golden marigolds ubiquitous with visits to mandirs across India. Half-price fireworks flanked lottery ticket machines and snatches of bright coloured saris could be glimpsed under the sombre practical overcoats of women buying vast quantities of groceries and pre-prepared snacks. Speaking with a sweet shop owner, she tells me of the surge in sales around religious holidays such as Diwali, though goes on to say that there are similarly increased purchases by her South Asian customers partaking in ‘British’ celebrations such as Christmas and the Royal Wedding.

The local flavour of Sikh Diwali celebrations in London is underscored by Mr Singh Bhasin, President of the Central Gurdwara committee. He laughingly concedes that concessions to Western attitudes are made in the replacement of the delicious (though ghee and sugar laden) mithai prescribed by tradition with the healthier alternatives of dried fruits and nuts. Celebrations will be held at the Gurdwara tonight after 6.30pm, in order to accommodate the working day and more importantly circumvent the draconian Kensington and Chelsea council parking restrictions. Yet in contrast to these practical considerations, certain things remain unchanged. He will depart our conversation to take part in the continuous recitation of the scriptures, spanning – I am told – around 40 hours, which occurs on auspicious occasions throughout the year. Every day the langar, a free meal donated to the Gurdwara prepared by volunteers and a pinnacle of Sikh faith everywhere, feeds over 100 people in the local community.

The colouring of diaspora religious celebrations by local events was highlighted tragically earlier this month. As I travelled on a bus surrounded by a sea of the crisp kurti and new salwar kameez of Muslims making their way to the Brick Lane Jamma Masjid for the celebration of Eid-al-Adha, the tangible excitement of some gave way to a more subdued atmosphere amongst others. Many spoke distractedly about Alan Henning, the British hostage whose execution was confirmed the night before. The muted festivities, and moving public expressions by Muslim leaders and individuals of outrage and sorrow, spoke hugely of another heavily South Asian religious community not distinct from British public sentiment but thoroughly influenced by and constitutive of it.

On that same weekend of Eid, on the other side of London, the normally staid Ealing Town Hall was awash with excitement and colour. The festivities of Durga Puja, the Hindu (particularly Bengali) celebration of the goddess Durga, were well underway amidst the thunderous sound of conch shells and drumming that accompany the prayers and offerings. Speaking with the officiating priest Shri Amiya Bhattacharya, he explained the significance of the goddess as a force of strength and unity whose annual visit serves to eradicate evil and division in society. Her return is also a homecoming, an element of poignant significance amongst the diaspora who themselves experience the celebrations as imbued with memory and nostalgia. Describing the rapt attention of the large audience as he recited the mantras, the pandit said:

they were not watching me, they are thinking about what they were doing when they were young. Everyone remembers something of the Puja of their younger days, or thinks of what their family and friends are doing in in India.

And what of those who are young today? The number of children and young people partaking in these diverse celebrations is striking. Naive assumptions that the festivities would be largely confined to members of the elder generation are dispelled by the presence of excitable toddlers and glamorous young adults. To class these events as solely religious is to overlook their hugely social aspect, and their capacity to provide younger generations with a means of accessing the history and experiences of their parents and grandparents. Though ‘selfies’ in front of vibrantly festooned pandals or even (controversially this year) at Mecca, form part of young peoples’ participation in these events, the celebrations offer an opportunity to experience practices intrinsic to their families and countries their parents or grandparents were born in, but which they themselves may never have visited.

Sitting in a conspicuous new café on Kolkata’s Park Street in January this year, it slowly dawned on me that the familiar music punctuating the chatter was an instrumental version of walking in a winter wonderland. As the CD languidly progressed through jingle bells, my thoughts were drawn to my own Christmas celebrations with my family weeks earlier, stark in their reassuring familiarity in contrast to this new and exciting city so far from home. To deem this musical interlude a colonial hangover or misplaced Western appropriation would be to miss its significance as a reminder of the power of celebratory occasions to invoke senses of home, the past and of the future. As many celebrate today, we will witness imaginings of family, devotion, nostalgia and those remembering places they do not want to forget, or imagining those they are yet to discover.

Happy Diwali!

About the Author

Lexi Aisbitt is a doctoral candidate in LSE’s Department of Anthropology. Previous posts by Lexi can be viewed here.

Lexi Aisbitt is a doctoral candidate in LSE’s Department of Anthropology. Previous posts by Lexi can be viewed here.