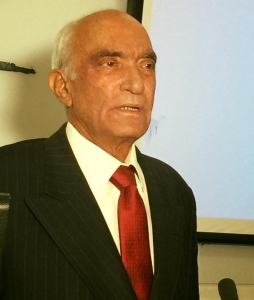

The LSE SU Pakistan Development Society recently co-hosted an event with Justice Ramday, who served as a judge in the Supreme Court of Pakistan for almost a decade. In this post Raza Nazar, who helped to organise the event, offers highlights from the wide-ranging discussion.

The LSE SU Pakistan Development Society recently co-hosted an event with Justice Ramday, who served as a judge in the Supreme Court of Pakistan for almost a decade. In this post Raza Nazar, who helped to organise the event, offers highlights from the wide-ranging discussion.

Earlier this year, the LSE SU Pakistan Development Society, in partnership with SOAS, organised ‘A Conversation With Justice Ramday’. This was an interactive discussion with the former Supreme Court Judge and centred around justice, the nature of the legal profession and contemporary legal issues in Pakistan’s society. The session was chaired by Dr Tahir Wasti and attended by students from both LSE and SOAS, who were encouraged to actively participate.

The Honourable Justice Khalil-ur-Rehman Ramday was an ad hoc judge later appointed as a permanent judge of the Supreme Court of Pakistan. He remained permanent judge of the Supreme Court from 2002 to 2010, and has held numerous visiting lectureships and Board positions at universities in Pakistan.

Justice Ramday gave an initial presentation on positive law, highlighting that ‘justice’ is defined as working within the limits conferred by a country’s legal system and that encroaching upon these is an injustice. He maintained that if a law is weak or ineffective, citizens should use democratic channels of assemblies and elected representatives to campaign for change.

Following the introduction, attendees moved the discussion from justice in its conceptual form to its practical application in Pakistan. Questions were asked about the separation of powers model and how that fits in Pakistan with regard to the government, parliament and the judiciary.

Justice Ramday was sceptical of applying the orthodox Diceyan notion that parliament is sovereign to ‘make or unmake any law whatsoever’. He argued that this line of thinking had to be contextualized, as the theory of parliamentary sovereignty was developed in a Britain where it was supposed that the Courts had no power to question any Act of Parliament. He continued:

We still somehow feel that whatever Dicey said was the principle of Pakistan. The situation in Britain (which Dicey spoke about) was absolutely different. It was said that the Parliament was sovereign or supreme. This works in the British context where the courts were always considered the representatives/agents of the Crown.”

In Pakistan, the Justices have reiterated several times in their judgments that the Supreme Court is a creation of the Constitution, and the same applies to Parliament and the Executive. The main task, as Justice Ramday highlights, is for each institution to work within the prescribed parameters and within the framework of Pakistan’s constitution.

This is justified. Article 8 of Pakistan’s Constitution states that “laws inconsistent with or in derogation of Fundamental Rights are to be void,” envisaging the power of the courts to strike down such laws as unconstitutional. In contrast, the United Kingdom Parliament is free to make laws even contrary to fundamental rights provided that it legislates clearly that it wishes to do so (in part because it does not have a single codified constitution).

It is key to note further that the judiciary has limitations which are also prescribed by the Constitution: “our institutions are all creatures of the Constitution” as Justice Ramday put it. He was keen to emphasis that in this context the Supreme Court is kept well separated from the executive.

The Ahmadiyya Community and minority rights

There is a significant controversy over the Ahmadiyya Community’s religious status in Pakistan. The community considers itself a branch of Islam, but the state of Pakistan has declared the community non-Muslim on the basis that the group does not accept the finality of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). The controversy has involved the persecution of the Ahmadis in Pakistan, which made this section of the talk was particularly interesting because it raised questions about the judiciary’s role in the protection of minorities.

Q: Under our present constitutional arrangement, is it for Parliament to decide whether Ahmadis are Muslim?

A: I don’t know but it is the Parliament which should be able to answer this question. Ahmadis were declared non-Muslims by Parliament in the 1974. No one questioned this act of Parliament and has not been questioned by any court.

This concerns a separation of powers issue. The law vis-a-vis Ahmadis was passed by Parliament and not the judiciary. To illustrate this, a certain minority group was outspoken in its criticism of the recently passed Women’s Protection Bill. It is not for the group to decide; it is for Parliament. If they would like the law to be repealed they must go back to the Assembly. By analogy, the same applies to the case of Ahmadis; only the Pakistan Parliament can undo this but it cannot be undone by the judiciary.

Q: Could it be argued that Article 8 of the Constitution (fundamental rights) must be invoked in such cases?A: This law (that Ahmadis are not Muslim) had been made by the Parliament and was never challenged in any court of law. Amendments are being challenged, but this second amendment passed in 1974 was, fortunately or unfortunately, never questioned in any court of law. This amendment was made by the Parliament and it is for Parliament to undo it. The answer is to gather and campaign. In today’s context, the judiciary is not answerable.

Justice Ramday’s responses were not satisfactory for one attendee, who continued:

You side stepped the issues about the Ahmadis, which is not an appropriate given the group has been indiscriminately targeted or persecuted. While this is a sensitive topic given the political tension, I don’t feel the matter was left in 1974 and that’s that. If there’s indiscriminate persecution – I do not think it’s fair to say that we should leave it there. We can’t say it has not been questioned.

This and other audience reactions highlighted that while it is easy to say that the ‘answer is to gather and campaign’, this does not reflect the practical realities of the country where the community faces widespread hostility. In light of this, should the courts not take an expansive – yet arguably defensible – view on Article 8 in saying that this law is inconsistent with fundamental rights? It could be defended on the grounds that everyone should have a fundamental right to religion, taken with freedoms of thought and speech. In a country that has a poor track record of success when it comes to democratic protest and campaigning for legal change it seems all the more important for the judiciary to guard the fundamental rights of Pakistanis.

The discussion of the Ahmadiyya Community transitioned to a wider conversation about minority rights. On the question of whether there is adequate protection of religious minorities such as Christians (in light of cases such as that of Asia Bibi, a Christian woman from Punjab who was sentenced to death for blasphemy), Justice Ramday was quick to point out that today not a single non-Muslim has ever been hanged. He further maintained that there is a misconception carried by people that Asia Bibi will not get justice from the courts.

Justice Ramday answered the final question regarding advice for law students and aspiring advocates in the United Kingdom who wish to return to Pakistan. He spoke reassuringly, “the lawyer’s work has always multiplied with each reform and step that is taken. There is always room at the top.”

Conclusion

Justice Ramday powerfully maintained that the judiciary is a vibrant and independent institution that is well separated from the politics of the country and wider power relationships. However, the discussion highlighted that it is possible to argue that the ongoing persecution of the Ahmaddiya community and the mistreatment of minorities is not reflective of a ‘vibrant and independent judiciary’. By virtue of the 1973 constitution, legal issues regarding particular communities are deeply connected to politics and the will of Parliament. Most audience members who asked questions passionately disagreed with the former Supreme Court Justice’s thesis, and instead argued that Pakistan needs greater judicial activism and perhaps a change of direction.

Click here to view the full video of the event.

The LSE SU Pakistan Development Society works towards empowering the youth, breaking stereotypes through awareness campaigns, and moving the discussion about Pakistan forward. It is the first of its kind in London and will be launching the ‘Future of Pakistan Project’ this fall, with a notable conference on November at LSE. Follow their Facebook page for updates.

Cover image: Scales of Justice. Credit: shabnam mayet CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Raza Nazar is studying Law (LLB) with specialisation in human rights and administrative law at the London School of Economics and Political Science and is President of the LSE SU Pakistan Society.

Raza Nazar is studying Law (LLB) with specialisation in human rights and administrative law at the London School of Economics and Political Science and is President of the LSE SU Pakistan Society.