The LSE India Summit in March featured a session on India’s foreign policy, featuring experts including four former Indian diplomats. After the discussion, Rebecca Bowers caught up with Ambassador Kanwal Sibal to discuss India’s foreign policy in more detail, particularly in relation to Trump’s America, West Asia and Britain on the brink of Brexit.

The LSE India Summit in March featured a session on India’s foreign policy, featuring experts including four former Indian diplomats. After the discussion, Rebecca Bowers caught up with Ambassador Kanwal Sibal to discuss India’s foreign policy in more detail, particularly in relation to Trump’s America, West Asia and Britain on the brink of Brexit.

RB: In your opinion, how might India and the US continue to maintain or even build on the ties of the Obama era with the Trump administration?

KS: Everybody is now concerned about the direction of US foreign policy. I was in Washington recently and even the Republican Senators and Congressmen, and the Democrats could not get clear answers. Trump made a lot of statements during his campaign and immediately after taking over, but then he has reversed his position on many of these issues. For example, on China, even on NATO he has stepped back. The Russians are now not very clear whether Trump will take steps to reset the relationship, even just in terms of co-operating and dealing with the Islamic State and Syria.

Our Prime Minister’s visit to the United States will be an occasion to clarify as to where we stand in terms of the strategic relationship that we built up during the Obama presidency, especially whether the Trump administration will be equally committed to join the strategic vision for Asia Pacific and the Indian Ocean regions. If you look at the geopolitical intention behind this joint vision it is quite clear that it is directed against instability.

Since this is a joint strategic vision between India and the United States of America, clearly India is not going to be the country that causes instability, nor will it be Japan, Korea, ASEAN, Australia etc. The only country is going to be China. Therefore, we need clarity about President Trump’s policy towards China because there have been a lot of contradictions. He himself began by questioning US commitment to the One China policy, which he reversed after a cell phone call with president Xi. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson in his Senate hearings said that the US will not accept the militarisation of islands in the South China sea, in fact they will impede China’s access to these islands. But subsequently, after his visit to Beijing, Tillerson has actually spoken in very accommodative terms about respecting each other’s concerns.

I might also say that Trump began by targeting Japan, which is very much an integral part of the joint strategic vision that we signed with Obama. For example, Japan has joined the Malabar naval exercises. These were previously bilateral, but both US and Japan were very keen that they should be trilateral. So Japan is a very important participant in what we are trying to do in the Indian Ocean and Asia pacific. America’s commitment to Japan’s defence is therefore also an important part of that.

So in short, we have a lot of work to do in trying to understand what Trump’s policies will be vis-à-vis China. Will they focus on the economic aspect or will they equally be addressing the security aspect?

Last year’s LSE India Summit featured a panel on West Asia. In foreign policy what would you say India’s primary objectives should be towards this area now?

West Asia is at the root of so many problems. One of course is that the key regimes of this area were destabilised as a result of military action which began in Iraq, followed by Libya, and then of course, Syria. The other is the rise of terrorism.

The whole Arab Spring built hope that there would be more representative governments and freedom, which would translate into economic growth and everything else. All of those hopes have been belied. In fact, the Arab Spring has, in the case of Egypt, opened the door to the Muslim Brotherhood, and retrograde kinds of Islamic forces who take over power on the basis of public support. So that experiment has failed and it will be a long time before it is reattempted.

The economies of the region have also been shattered, as a result of which now you have the whole problem of refugees, who are heading to Europe, and causing serious domestic problems there. Then there is the whole policy of Erdogan in Turkey, which to my mind is very disruptive, because he is committed to the Muslim Brotherhood thinking and ideology, leavened with Ottoman ambitions, so he is not playing a stabilising role in the region.

Finally, Saudi Arabia and others have their own agenda, because they want to counter Iran’s influence in the region. The Shi’ite influence is viewed as a problem for the Sunni monarchies in the Middle East. The Unites States and Israel also have a negative view of Iran’s role. Therefore they are also playing politics in the region which has not actually achieved the right balance.

I don’t think we are going to see the end to these conflicts quickly, unless the United States gets Russia, Turkey, and Iran to join hands together to have some kind of a concerted view on stabilising the region.

With this in mind, what would you say are the greatest challenges currently facing Indian foreign affairs today?

We have multiple challenges. China’s rise has created serious instabilities, firstly in the Western Pacific, and the South China Sea. Its expanding geopolitical ambitions are there to see, represented by this One Belt One Road project, where China has two objectives. Firstly it aims to expand its geopolitical reach. It has been blocked in the Western Pacific because of the military treaties America made with key countries. The US created a cordon, known as the first island chain, to keep China bottled in. This includes Taiwan, Japan and the Philippines. Since China can’t break out they have started expanding westwards through these two corridors, in Myanmar and Pakistan.

In this way they are getting entry into the Indian Ocean, something which the British denied to Russia for a couple of centuries in order to curb the expansion of Russian power. So this access to the warm water is an expansion of China’s Asian power. As there is no willingness to counter this either on the part of the United States or Europe we have to cope with this.

Furthermore, China now has a geopolitical commitment to Pakistan because of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Pakistan has become a lynchpin for the larger geopolitical strategy for China to expand on the Eurasian subcontinent, to the Indian Ocean and across to the Gulf. This means that China will continue to give even greater support to Pakistan against India. We have begun to see the first signs of this by linking our entry into National Security Council with Pakistan, by preventing the designation of Masood Azhar as an international terrorist by the UN Security Council, even when the organisation he leads has already been declared as a terrorist organisation.

We’ve not found an answer to our problem of Pakistan’s sponsored terrorism, because the concern is that if we retaliate things may get out of hand. Pakistan has nuclear weapons and we just don’t want to take that kind of risk, especially when Pakistan is making loose statements about using it nuclear power against India.

The next issue is linked to Pakistan but goes beyond it. This is the link to extremism and the rise of radicalisation of the kind that we are seeing now in West Asia and the risk spill over into our region. The Islamic State has a presence on Afghanistan and they can emerge in Pakistan, which could lead to pressure on India. How can we evolve a consensus that includes all the relevant countries and curb this? I am not too sure.

The other problem is US pressure on Iran is not conducive to other regional interests because Iran is an important energy partner, and a very important transit state. It gives India access to Afghanistan and to central Asia. At the same time, we are not in the position to challenge the United States in its policies towards Iran, and nor do we want to because our businesses and financial institutions are unwilling to risk getting on the wrong side of the US sanctions law.

And finally, there is US-European Union pressure on Russia. From the Western side, there may be arguments in favour of doing this as a response to Russia’s conduct in the Ukraine, or the annexation of Crimea, but from our point of view, it has pushed Russia into the arms of China. So this combination of Russia and China is not helpful to our interests. This increasing alignment has began to affect already Russian policy in our own region. After a gap of years, Russia has began making approaches to Pakistan, even military approaches, joint exercises and so on. Russia is arguably not too happy at the manner in which India strengthened relations with the United States so part of the reason for what they are doing in our region could be to obtain leverage against us. From our point of view then, if Trump could find a way to move forward in relations with Russia, it would be better for us. If Russia’s own relations with the US begin to improve then they will lose the argument that India’s growing relations with the United States are objectionable.

With Brexit and heavy restrictions on Indian student and national visa applicants, what would you say the future has in store for Anglo-Indian relations in this period of uncertainty and transition?

First of all, Britain will remain a very important partner of India, irrespective of whether it’s inside Europe or outside Europe. That relationship is not going to be affected. Apart from certain issues on tariffs and trade, in every other field, there are no restrictions on Britain or on India to a bilateral partnership. I don’t think India has to go through Brussels to deal with the financial sector in London, nor does it affect our business people establishing offices or investing in Britain. So there are a whole range of policies and interactions between Britain and India which have occurred and which will continue to occur outside of the control of Brussels.

In terms of trade policy, Britain cannot sign trade agreements with any other country, or trade agreements because until it delinks itself formally with Europe. It can put a negotiation process into action and prepare the ground for an eventual quick agreement. However, Britain will certainly lose standing in the eyes of Indian businessmen and investors, because as long as it was part of the European Union, they felt that it was extremely congenial and they would prefer to take the protection of the British laws and make London as a headquarters for some of their investments and outreach to Europe. Now they might have to revise that. Again, it will depend on what the negotiations will yield.

The other issue is that Brexit is likely to impact the British economy. If it does prove costly and there is a drop in growth rates then clearly Britain becomes less attractive as a destination. That’s all speculative at the moment, but there are credible voices from Britain that don’t draw a very happy picture of post Brexit Britain, which can’t be ignored by Indians.

Thank you so much for your contributions and insight, Ambassador Sibal.

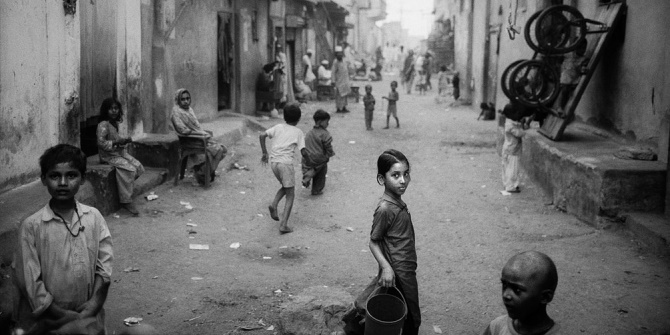

Cover image: President of China, Xi Jinping. Credit: Foreign and Commonwealth Office CC BY 2.0

You can watch the India @ 70: LSE India Summit Foreign Policy Panel here or read the event summary here.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Authors

Kanwal Sibal is a retired Indian diplomat and former Foreign Secretary. He served as the Ambassador of India to Turkey, Egypt, France, and Russia. Dr Sibal has also served on India’s National Security Advisory Board.

Kanwal Sibal is a retired Indian diplomat and former Foreign Secretary. He served as the Ambassador of India to Turkey, Egypt, France, and Russia. Dr Sibal has also served on India’s National Security Advisory Board.

Rebecca Bowers is a final year PhD student in the Anthropology Department at the London School of Economics. Rebecca’s research explores the lives of female construction workers and their families in Bengaluru, India.

Rebecca Bowers is a final year PhD student in the Anthropology Department at the London School of Economics. Rebecca’s research explores the lives of female construction workers and their families in Bengaluru, India.