Countries are beginning to submit their first voluntary reports to the UN reviewing progress on the Sustainable Development Goals. However, the reports so far have focussed heavily on identifying indicators for outcomes. If the SDGs are to be achieved, innovative approaches to monitoring and evaluation and better data at all levels will be required, writes Diksha Singh.

Countries are beginning to submit their first voluntary reports to the UN reviewing progress on the Sustainable Development Goals. However, the reports so far have focussed heavily on identifying indicators for outcomes. If the SDGs are to be achieved, innovative approaches to monitoring and evaluation and better data at all levels will be required, writes Diksha Singh.

Last month, India submitted its first Voluntary National Review (VNR) on the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to a High Level Political Forum (HLPF) of the United Nations. As part of its follow-up and review mechanisms, the HLPF encourages member states to conduct regular reviews of progress at the national and sub-national levels, which are voluntary, state-led and involve multiple stakeholders.

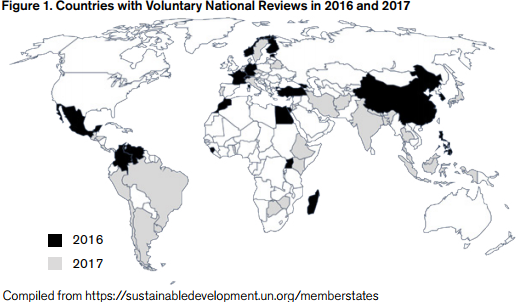

- In July 2016, the first 22 countries presented their reviews.

- In 2017, a second group of 44 countries, including India, promised to follow (Figure 1).

- Another 50 countries are expected to follow suit over the next two years.

However, a preliminary review of the first set of 22 VNRs and India’s review, point towards a glaring gap in the use of evaluation as a tool to support policymaking in the run up to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. It appears that the reports lay too much emphasis on identifying indicators for outcomes, instead of providing a comprehensive framework within which outcomes and impact can be evaluated.

Monitoring alone is no longer enough

Since the adoption of the Agenda for Sustainable Development in 2015, there has been considerable discussion around the importance of measuring progress using better data. Entrusted with the responsibility to oversee India’s SDG agenda and implementation, the Government of India’s think tank NITI Aayog has undertaken a mapping of the SDG targets to nodal ministries, centrally sponsored schemes and related interventions. In a parallel exercise, the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation is preparing a National Indicator Framework for SDGs, which was shared for public comments earlier this year. The results of the exercise are expected to be out shortly.

While India is no stranger to monitoring programme implementation, this has not always moved in tandem with evaluation, as in other countries where evidence-informed policymaking has caught on in the last decade or so. Earlier efforts to institutionalise evaluations have had a mixed record. Set up in 1952, the erstwhile Planning Commissions’ Programme Evaluation Organisation’s (PEO) original mandate was to undertake independent evaluations of programs. It was subsequently entrusted with providing guidance for the formulation of a national evaluation policy (NEP), and developing evaluation capacity. However, even after six decades of the PEO’s existence, there is no sign of the NEP and the organisation has done little to create a favourable policy environment for rigorous evaluation. An Independent Evaluation Office, set up under the previous Central Government regime in 2013, was short-lived.

The global scenario, however, paints a different picture. Policymakers at the highest levels are increasingly relying on insights from scientific evaluations to inform decision regarding programme design and delivery – from Mexico’s Coneval, to the UK’s Behavioural Insights Team, to the Social and Behavioral Sciences Team at the White House. Grounded in a nuanced understanding of human needs, preferences and biases, such evaluations can provide important insights into some of the most pressing challenges in international development, such as the chronic absenteeism of public school teachers and community health workers, poor uptake and usage of savings and insurance products, and the question of whether unconditional cash transfers can improve welfare. For instance, evidence from evaluations of BRAC’s Graduation Approach in India and five other countries suggests that providing ultra-poor households with a productive asset, training, regular coaching, access to savings, and consumption support can lead to large and lasting impacts on their standard of living across a diverse set of contexts and implementing partners. Similarly, evidence from a study on absenteeism of nurses conducted in Udaipur suggests that monitoring, coupled with punitive pay incentive, reduced the absence of nurses from 60 per cent to 30 per cent in healthcare centres.

Thus, while conventionally popular monitoring and evaluation (M&E) approaches such as outcome budgeting and strengthening of management information systems are necessary to pin accountability, they need to be coupled with innovative approaches that leave room for iteration, and tweaking of interventions based on insights from the field.

Bigger, better data

As we inch closer to finalising the SDG indicators, there is a pressing need to improve the quality, frequency, and disaggregation of data as well. This is vital, especially in the case of data sectors such as employment, informality, gender, and small businesses, which pose considerable challenges in terms of collection and verification. In the absence of reliable baseline estimates for the targets at hand, the task of evaluating the success of SDGs is likely to be fraught with challenges. In this regard, NITI Aayog has announced a slew of new initiatives in the VNR which include quarterly labour force surveys on employment/unemployment and time use surveys to assess the gendered nature of economic disparities. At the same time, growing penetration of ICT and mobile phone usage generate rich digital data trails which can complement traditional data collection efforts, and inform the design of development programs. Even so, harnessing the potential of alternative data requires partnerships between governments, private sector and civil society, and appropriate safeguards to protect the interests of all people, especially those from vulnerable sections of society.

Looking ahead

By pledging support to the voluntary review process, NITI Aayog has demonstrated its commitment to monitoring the SDG agenda and has taken definitive steps to engage key stakeholders from the Centre and States. However, given the federal structure of policymaking in India, much needs to be done to strengthen implementation and evaluation capacity at sub-national levels. With nearly US $0.96 trillion at stake to finance India’s SDG efforts in the marathon to 2030 (Bhamra et al, 2015), India can no longer afford to waste public and private resources on populist schemes with little track record. The need of the hour is to identify interventions and approaches which demonstrate impact and are cost-effective at scale.

Cover image credit: IAEA Imagebank CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Diksha Singh is a Policy & Outreach Manager at IFMR LEAD. She is interested in connecting the dots between research, policy and practice through her work. At LEAD, she engages with key stakeholders to identify priority areas for research and evaluation, build partnerships for influencing policy dialogues and outcomes, and leads outreach campaigns. Diksha holds a Master’s Degree in Economics from the University of Mumbai. Her research interests include gender, behavioral economics, and the workings of public policy.

Diksha Singh is a Policy & Outreach Manager at IFMR LEAD. She is interested in connecting the dots between research, policy and practice through her work. At LEAD, she engages with key stakeholders to identify priority areas for research and evaluation, build partnerships for influencing policy dialogues and outcomes, and leads outreach campaigns. Diksha holds a Master’s Degree in Economics from the University of Mumbai. Her research interests include gender, behavioral economics, and the workings of public policy.