In their examination of recently released census data, Saad Khan and Dr Muhammad Adeel write that not only has the urban population been undercounted, but that there exists an urban bias that is affecting vital service delivery to the rural and peri-urban populations in Pakistan.

The Pakistani government has started releasing data from the sixth national census. The count was already almost a decade overdue and took more than a year of manual door-to-door data collection and analysis. Provisional results show the country’s population increased to approximately 207.8 million from 132.4 million since 1998, i.e. by 57%. The overall figures are not that different from expectations but there is one surprising result: there are now 105 males for every 100 females, down from the 108 males to 100 females ratio in the 1998 census.

The hottest topic in Pakistan, however, is that of great disparities between the urban/rural ratios and the alleged under-counting of Karachi’s population. The majority of academics and professionals believe that the share of urban population has been undercounted. The question around how much of our population is urban remains a longstanding point of debate. Believing that national estimates are quite low, professionals from different disciplines have advocated different criteria, resulting in varying estimates.

Economists, who think the delineation between the urban and rural classifications should be made on the nature of production, have questioned the parameters used in the census figures. Akbar Zaidi, a noted political economist, believes rural areas now constitute only one-fifth of Pakistan’s population. This estimate relies on agriculture as the means of production for a true rural area and its share in the national GDP. Pakistan now generates up to 80% of GDP from the non-agricultural sector, triggering a massive migration towards urban areas. Other social scientists believe that urban is a combined function of accessibility, density and population threshold, and argue the figure is closer to 60%.

For the state, it appears the identification of ‘urban’ areas is a complex administrative matter. The definition of urban areas follows pre-defined historical criteria and the urban/rural dichotomy of an area is fixed before counting. Earlier urban commentators, such as Reza Ali, have asked why suburban residential communities around Lahore were not considered urban, even though they were provided with urban services. It seems their observation was accepted and Lahore district was reclassified as urban.

The question then arises: if the entire Lahore district is urban, why not Islamabad and Karachi? Islamabad’s ‘rural area’ – where residential expansion is now legal by law, contrary to its original master plan – is now home to almost half of the entire population of the Islamabad Capital Territory. If the rural population is taken into account, this area becomes the sixth largest city in Pakistan, with a total population of two million.

In Karachi, too, multiple residential projects have appeared along the Super Highway, in what was earlier demarcated as a rural area. Bahria Town and DHA City are two prime examples of this expansion, yet these areas are considered as rural in the census. As a result, the census indicates Lahore has a population of 11.1 million while the Karachi has 14.9 million. People who know both cities question that Karachi should be much bigger than Lahore. Others argue that some areas of Karachi are quite dense due to multi-storey apartment developments which should be reflected in the population comparison between both cities.

More importantly, any debate about urban expansion should acknowledge the vertical versus horizontal expansion trends. Lahore has seen a horizontal expansion where people prefer to live in detached houses – and there is ample room available to accommodate this preference. In the congested environs of Karachi, multi-storey apartment buildings have long ruled the roost. Poor implementation of building codes and rampant corruption has resulted in an upsurge in converting smaller residential plots – originally meant for detached houses – into multi-story buildings. It is not unusual to find a multi-storey building on a small 80-square-yards plot in many areas of Karachi – and the illegal/shoddy construction often results in bad consequences. There were complaints among some quarters that the enumerators only knocked on the ground-floor-doors of such buildings, ignoring those residing in the upper floors. Given the anomalies and unique urban footprint of the city, the margin of error in data collection for Karachi’s population is likely to be considerable.

To a certain extent, the belief that census estimates are off the mark relates to perceptions and interpretations of what is ‘urban’. My earlier work six months ago found that urban footprint of Karachi is just 16% larger than Lahore. We will have to wait for the release of disaggregated data for further clarifications.

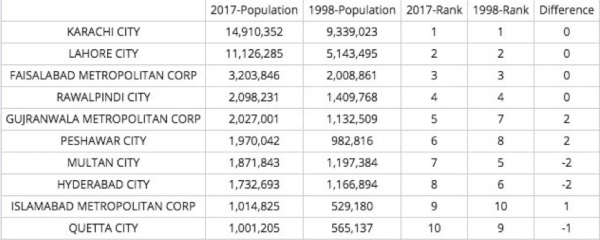

Table: Ten largest cities of Pakistan and their estimated population in 2017 and 1998 census: Note that city population rank changed for Gujranwala and Peshawar by +2 and decreased for Multan and Hyderabad by -2: largest change. Source: Muhammad Adeel

The urban-rural debate represents the resentment many Pakistanis feel towards their agricultural roots – “Paindoo” or one who hails from a village is widely considered a pejorative in urban vernacular. The social stigma attached with village folk persists, even though many contemporary urbanites were once villagers themselves. More importantly, the government appears to have perpetuated this stigma. Rural areas remain deprived of basic necessities of life. One often has to walk miles to a school or a basic health facility, which, ironically, is often staffed by non-professionals as doctors resent serving in villages. Such is the pervasive discrimination against rural areas that those now fully absorbed under metropolises still have poor coverage of government schools or hospitals. Even the modern capital city of Islamabad has a dearth of government schools or clinics in the rurally-delineated-but-now-urban areas.

This trend is not limited to Pakistan. India, Bangladesh and scores of other developing countries reflect similar circumstances. Significant work needs to be done to bridge the gap between the urban-rural divide and provide rural areas with some semblance of civil infrastructure and basic education and health facilities. Similarly, so-called urban areas are teeming with problems of their own. Haphazard expansion, poor civic infrastructure, overburdened schools and hospitals; and the growing menace of pollution define modern South Asian cities.

Ideally, focus should be on the quality of life, irrespective of the urban or rural nature of dwelling. Pakistanis, and the rest of South Asia, need to evaluate the consequences of their urban bias. As for the results of the latest Pakistani census, one should wait for the final figures and then focus on areas requiring immediate attention. It would be more prudent to analyze why there are so fewer doctors and teachers to particular demographics of population.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Authors

Dr Muhammad Adeel is an urban planner from Pakistan and works as Research Officer in LSE Cities, at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He tweets @DrAdeelM

Dr Muhammad Adeel is an urban planner from Pakistan and works as Research Officer in LSE Cities, at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He tweets @DrAdeelM

Saad Khan is a freelance political and global affairs analyst from Islamabad, focusing on Middle East, Asia-Pacific and U.S. Politics. He tweets @Real_Opinion

Saad Khan is a freelance political and global affairs analyst from Islamabad, focusing on Middle East, Asia-Pacific and U.S. Politics. He tweets @Real_Opinion

The countries in which the bias was most pronounced are those like China and Soviet Russia — where the discrimination was once a key part of the development strategy. You might even reach back to medieval Europe as documented by Henri Pirenne.