The recent exhibition, ‘Letters from Arakan’, featured hand-written letters and audio clips alongside portraits of survivors of the brutal military and militia attacks taking place in the Rakhine State. For Adib Chowdhury, the photojournalist who put the project together, the impetus behind the project was to ‘let the Rohingya tell their story through me’. The full project can be viewed on his website.

The recent exhibition, ‘Letters from Arakan’, featured hand-written letters and audio clips alongside portraits of survivors of the brutal military and militia attacks taking place in the Rakhine State. For Adib Chowdhury, the photojournalist who put the project together, the impetus behind the project was to ‘let the Rohingya tell their story through me’. The full project can be viewed on his website.

Noor aged 32, has 6-month-old twins. Her husband Dildar worked as a shopkeeper in their village in the Maungdaw District, Myanmar. Typically, women in the rural areas in Rohingya villages do not attend school for many years. Her husband wrote her message. It reads:

We are citizens of Burma. Aung Sung Suu Kyi can save our citizenships and keep us in our land but she gave power to the hands of the Army Chief Min Aung Hlaing, and in doing so gave him the power to kill us. When the military find us in the open, they shoot brush (indiscriminate) fire at us, old people, children, women, everyone gets hit by the bullets. They raped them. They raped the women. They burnt our villages to the ground. The villages are gone. We are Rohingya, our home is Arakan. We will only go back if they [the Burmese government] can accept us as Rohingya.

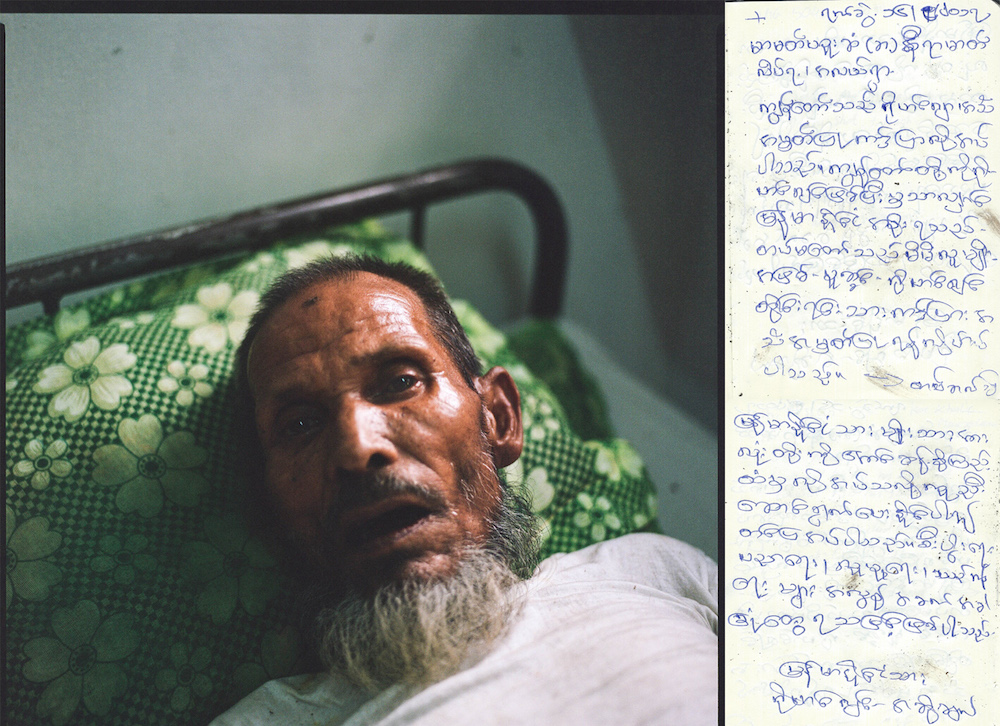

Nur Mohammad, aged 75, worked as a fisherman in his village in Kor Khali, Maungdaw, Myanmar. When the army launched attacks on his village on the 30 August he was fishing. Upon seeing bullets flying over his head from the nearby houses, he ran towards the trees. Whilst running he heard a helicopter hovering above him. It began circling around the village before flying directly over him. He saw grenades being tossed out of it. One of the grenades caught him with the explosion ripping apart the sides of his legs. His wife also managed to escape but fractured one of her hands during the commotion. A daughter of his was injured during the attack and he does not where she is, or if she survived the attack. The rest of his family is in Kutapalong refugee camp a few miles away from the hospital he is in. his letter reads:

A while back the Burmese government gave us assurance that they will give us citizenship rights, but they lied. We demanded that the citizenship rights should be granted to our Rohingya identity but they denied it and they tortured us cruelly for it. We cannot have our Rohingya identity in Burma, but others outside accept us as Rohingya. Burma has always been our home. And now as we ask for the right to our identity again, the government launches attacks on us again. They burn our villages, they force us to leave our land, even Aung Sun Suu Kyi does not accept us our rights despite supporting her in previous years.

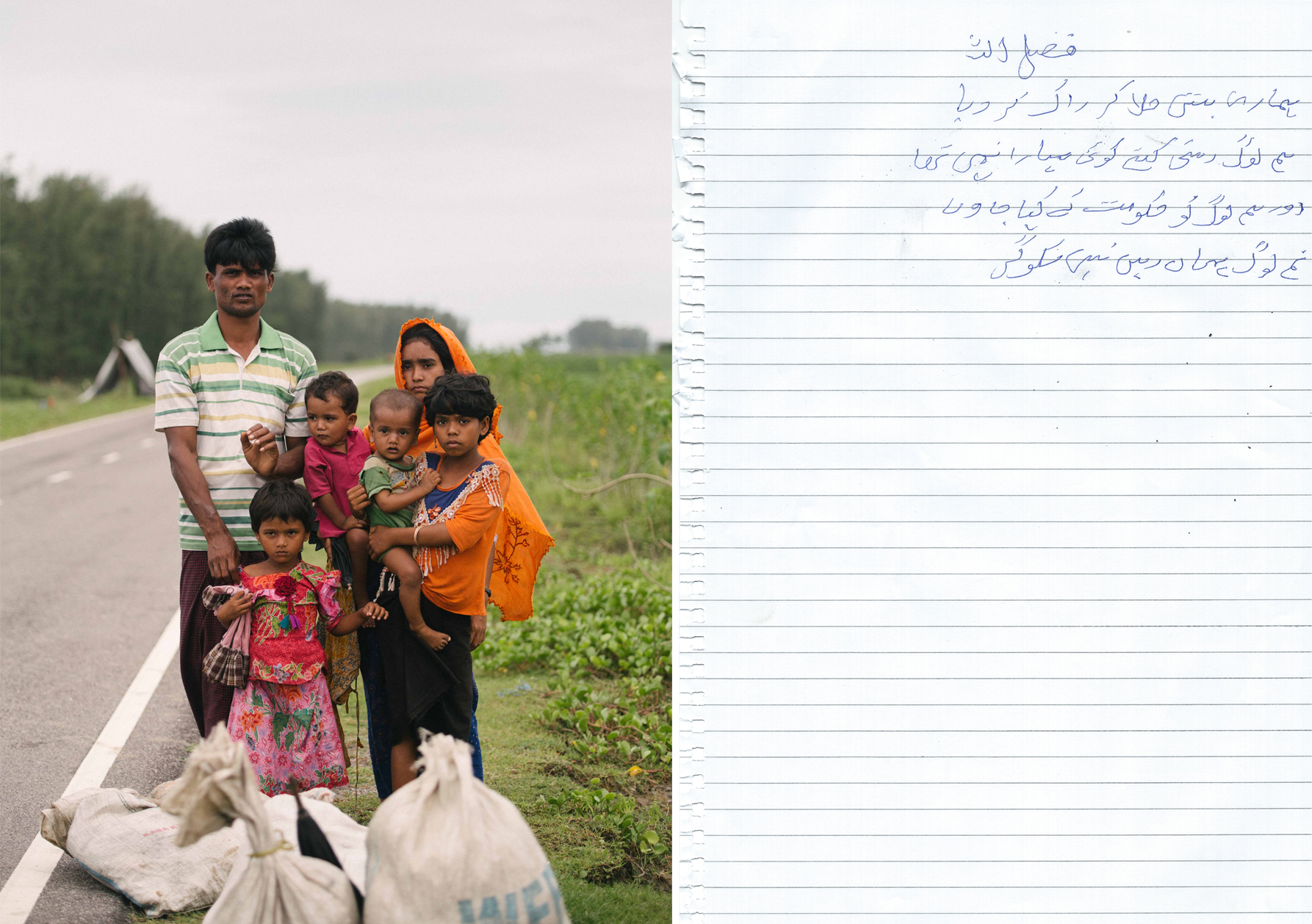

Mohammed and his family fled from Rathedaung, Burma. The journey, largely undertaken through the dense jungle and wading through thick mud across paddy fields, has taken them four whole days. They carry with them all their belongings and two babies -aged two and three- and fled after the Burmese army started burning homes and shops in their village. They witnessed many of their neighbours being shot by indiscriminate gunfire and estimate around 200 people in the village were killed including the husband’s father who had his stomach slashed open by the Buddhist militia. Before arriving at the Bangladesh border, the boat driver who offered them a lift demanded money from them. Having no money to offer, the husband paid through giving the driver his wife’s necklace, earrings and rings. His letter reads:

The Burmese military burnt my house down and then told me that Burma is not my country. They told me to get out of their land, but I don’t know anywhere else that is home.

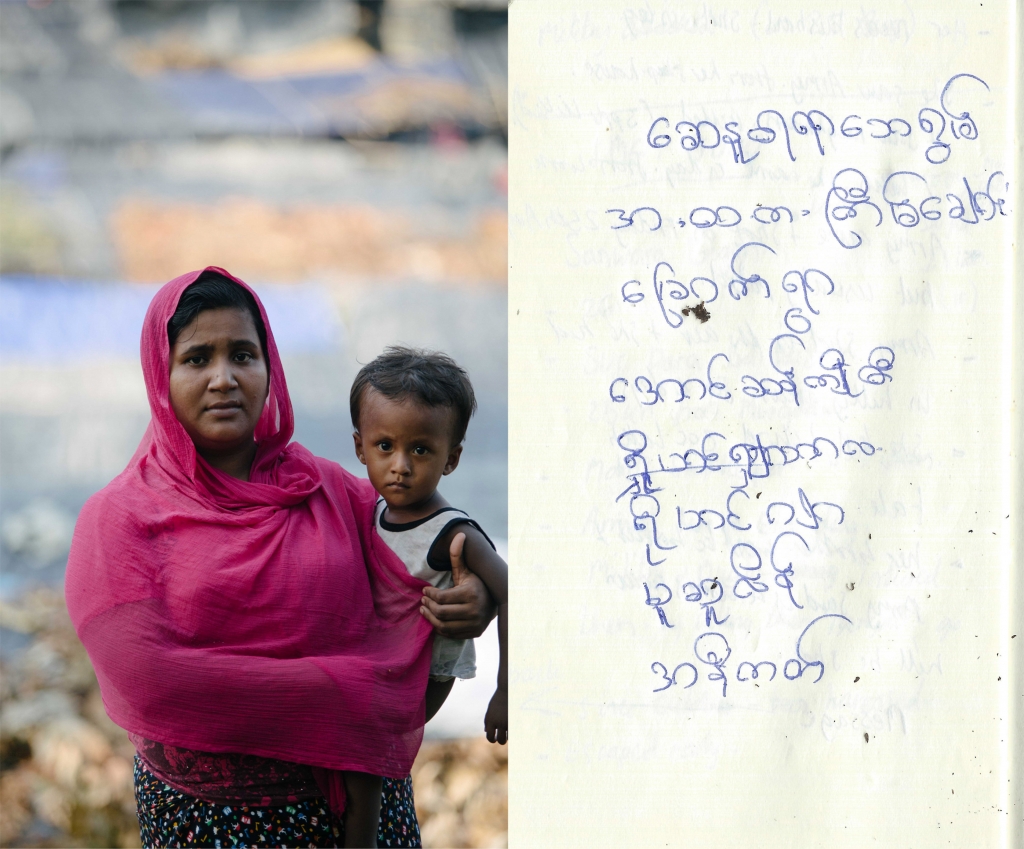

Sanwara, 26, fled her village with her two boys, aged 1 and 10. Her letter reads:

I am Sanwara Begum from Boli Bazar, Burma. I have two children and a husband and fled from the Mogh [Buddhist militias] who came to our villages and started shooting at us.

Mohammed crossed the border into Bangladesh via the Tomuru border with Bangladesh where mines have injured and killed several refugees fleeing Burma. The night before August 25 he heard firing and clashes with the Burmese military for about 2 hours deep into the night. The next day the military arrived at his village and shot into it before dousing petrol over houses. The soldiers and militiamen were armed with long knives and rifles [G3 and AK47’s]. They rounded a group of people from the village into a nearby field, separating the men from the women. The women were taken inside a large house and began to start screaming. Outside, the men were lined up and shot behind the head. Those that survived the initial shootings were executed by the Buddhist [militia]. After, the house which contained (he estimates a few hundred women from the village) was shot into and then set on fire.

Later, around 6 army trucks arrived to take away the bodies to a nearby military outpost a mile away. Around 300 men from the village were captured. 100 escaped into the nearby jungle, and 200 died in the fields after being rounded up and shot or executed. Mohammed watched this as he hid paralysed in fear amongst trees overlooking his village. His letter calls for justice:

My name is Mohammed Shofi, I am 20 years old from Buthidaung, Burma. The Burmese military came into my village and started to round up and shoot many men and women. I want the world to call for justice for what happened and for action to be taken for the people that died.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Utilising his academic background in international Conflict studies from the London School of Economics, Adib Chowdhury‘s work focuses on documenting how conflict shapes identity as well as looking at issues surrounding forced migration, identity, and the environment. Adib’s work has been published in BBC World Service, Financial Times, WIRED, and Post Internazionale amongst others. He was awarded the Marty Forscher Fellowship Fund for humanistic photography, as well as the PDN Annual 2016 and shortlisted for the Lucie Foundation scholarship 2017. He tweets @adibchow and you can see more of his work at www.adibphotography.com.

Utilising his academic background in international Conflict studies from the London School of Economics, Adib Chowdhury‘s work focuses on documenting how conflict shapes identity as well as looking at issues surrounding forced migration, identity, and the environment. Adib’s work has been published in BBC World Service, Financial Times, WIRED, and Post Internazionale amongst others. He was awarded the Marty Forscher Fellowship Fund for humanistic photography, as well as the PDN Annual 2016 and shortlisted for the Lucie Foundation scholarship 2017. He tweets @adibchow and you can see more of his work at www.adibphotography.com.