Every 12 years, thousands of people gather in the Southern Indian state of Karnataka to witness the Mahamastakabhisheka or the ‘Great Head Anointment’ of the 57-foot high statue of Bahubali. This photo essay captures the nearly thousand year old ceremony, which has been embellished with some 21st century additions in the form of material and technological changes. Text by Sweta Daga and Dhruva Ghosh. Photos by Rajiv Rathod, Sweta Daga, and Dhruva Ghosh.

In February 2018, thousands of people lined up the slopes of Vindhyagiri at Shravanabelagola in Karnataka waiting patiently for a glimpse of grand celebrations. Shravanabelagola (meaning ‘white lake of the sramanas’), is a pilgrimage for all digambara Jains.

Jains and Buddhists are the two surviving schools of the ancient sramana traditions of the Indian subcontinent, and the digambaras are one of the two major sub-sects of the Jain community. The Kannadiga Jains of Karnataka are historically a part of the digambara tradition. Jains account for less than 1 percent of the Indian population, and Kannadiga Jains are a small group within the Jain community. Historically, Jains have had great influence in the region, and the earliest recorded literature and culture of Karnataka belongs to the Jain tradition.

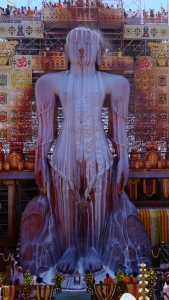

At Sharavanabelagola, a giant monolith of a man standing in meditation is bathed in sacred substances once every 12 years. The statue is of Bahubali, one of the most popular characters in Jain mythology. Locally, this monolith is also known as the Gomateshvara. Coconut water, sugarcane juice, milk, turmeric, perfumes, medicinal herbs, sandalwood, vermillion, etc. are poured on the head of the idol from pots carried by devotees up a scaffolding set up behind the idol which is more than 57 feet high. These substances are typically poured from 1008 kalashas or pots on each day for about two weeks.

This ceremony is known as the Mahamastakabhisheka, or the Great Head Anointment. Though it happens in Karnataka this is not just a festival of Kannadiga Jains, digambara Jains, or even just Jains. People of all religions from all parts of the country, and perhaps across the world visit Shravanabelagola during the festival.

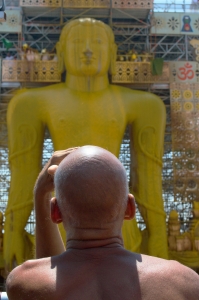

From top left, clockwise: 1. Bahubali is one of the most popular figures in Jain mythology. His name means ‘one with strong arms’. 2. The rituals of the abhishekam depend on traditional memory. 3. Since the festival is so significant, people pay large amounts of money to pour sacramental fluids onto the idol’s head. 4. Monks of the digambara sect do not wear clothes at the highest levels of their practice; clothing is considered to be a kind of attachment. 5. Though Jainism does not believe in a creator god, there is often a strong sense of devotion towards the liberated souls. 6. Like Bahubali, Jain practitioners hope to defeat all inner enemies and attain eternal bliss.

Traditions and transformations

The monks of the digambara Jains go naked as a performance of extreme austerity, but technological advancement and material comfort does inform the rest of the community, which lives a well-integrated life within India. Jain temples and sites too continue to incorporate modern amenities.

This year’s Mahamastakabhisheka was also augmented with lots of modern technology. For example, the metallic scaffolding employed German technology instead of wooden logs. Guests were allocated computerised passes, and logged at entry gates using handheld digital scanners. Police and personnel deployed for security had all advanced communication devices and so on available to them. A website, Facebook page, mobile app, Twitter account, etc. were also set up for this iteration of the ceremony. Multiple 360-degree virtual reality (VR) livestreams of the event were also available for viewers across the globe. This is a big leap considering that Jain ascetics themselves typically only travel within defined geographical boundaries, and only as far as they can travel on foot.

Such events are often resource intensive. For example, by some estimates, about 8000 litres of milk have been used for consumption and for the rituals on each day of the festival. The Indian Railways ran 12 special train services for this festival. The local government earmarked Rs 175 crore (€21.79 million) for developing infrastructure in and around the site for this festival.

Changes are not just of a material and technological nature. For the first time since the Mahamastakabhisheka started a thousand years ago, the festival committee is being headed by a woman.

According to anecdotes, the first iteration of the Mahamastakabhisheka was conducted under the purview of Chavundaraya, a general of the Ganga dynasty (which ruled the region approximately between 350 CE and 1000 CE), who is also credited with having commissioned the monolith sometime between 981 CE and 983 CE. Abhishekam is not unique to Jainism, and is a ritual in many Indic religions. Other digambara idols, especially of Bahubali, have their own abhishekam ceremonies.

A lonesome liberation

Jains do not believe in a creator-god, but do believe that every being has an independent soul which can attain liberation, or moksha, from the cycles of deaths and rebirths. Moksha is preceded by enlightenment within a perfected human form. Bahubali depicts such an ideal.

According to Jain mythology, Bahubali almost overcame his brother Bharata in a fight, but during an epiphanic moment in the final stages of battle, decided to give up the material world. He stopped fighting, gave up his possessions, and entered meditation in the kayotsarga posture, which the statue depicts. It is thought that vines grew around his legs during his long and intense meditation, and that there was a final impediment to his enlightenment. In one version, the impediment was his hesitation that he was still standing on ground that belonged to his brother. In another, it was his regret that he was the cause of his brother’s humiliation. In yet another version, it was his own ego at having sacrificed everything. That too, he gave up the moment he realised it.

While the soul that was once called Bahubali has departed from the churning worlds, its story still remains with us, as do its idols. Bahubali stands tall and steady, in stone as in mythology, stripped bare of all worldly things, testament to the final, indescribable bliss of the transcendental cosmic absolute.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About The Photographers and Authors

Rajiv Rathod, Sweta Daga, and Dhruva Ghosh are members of Jainism.com, and are working on a feature-length documentary film on Jainism.