Why are more than 80% of women in the world’s fastest-growing major economy out of the labour force? Mitali Nikore (Assistant Director, School of Economics and Commerce, Adamas University, Kolkata & LSE alumnus) explores this question by analyzing trends in employment related data over the last seven decades (1950 – 2018). She finds that India’s female labour force participation rate has fallen to its lowest points since Independence; women’s employment is concentrated in low-growth, low-productivity sectors; and the gender wage gap is sticky, with the female wage being 60-65% of the male wage since the last three decades. She calls on all relevant stakeholders – the government, corporate sector, civil society and the media to find long-term solutions for this multifaceted conundrum.

India is an economic powerhouse on the global stage. It earned the title of the world’s fastest-growing major economy in 2017, maintaining GDP growth above 7% p.a. since 2011-12. For India’s women however, the year 2017 was significant for another reason – it was the year in which India’s female labor force participation rates (FLFPR) fell to its lowest level since Independence. World Bank (2017) notes that India has amongst the lowest FLFLPRs globally, with only parts of the Arab world being lesser.

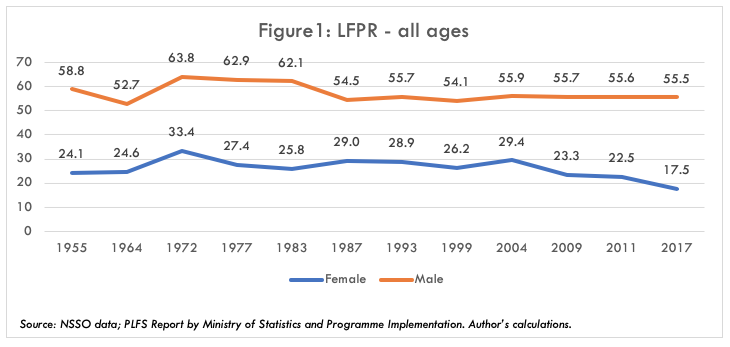

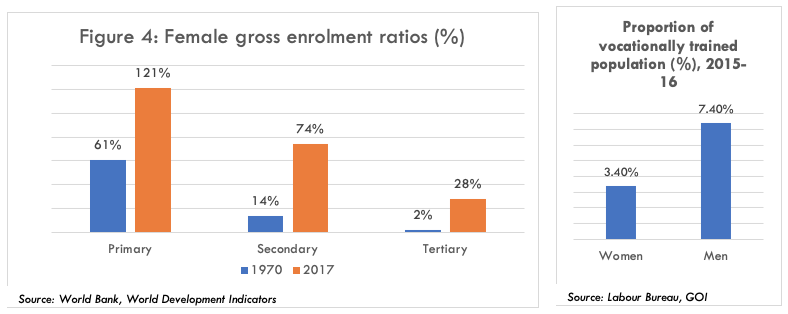

This exodus is not sudden, rather women’s participation in the labor force has shown a consistent decline over the last seven decades (figure 1). The FLFPR peaked at 33% in 1972-73 and showed a decline till 1999-00, when it touched 26%. At 17.5% in 2017-18, it is at the lowest ever in Indian history. This presents a strange conundrum: why is it that a country seeing considerable gains in female education, remarkable decreases in fertility rates, and increasing economic growth is not seeing a greater participation from women in the workforce?

The story behind the data: Occupational segregation and concentration of women in low growth sectors

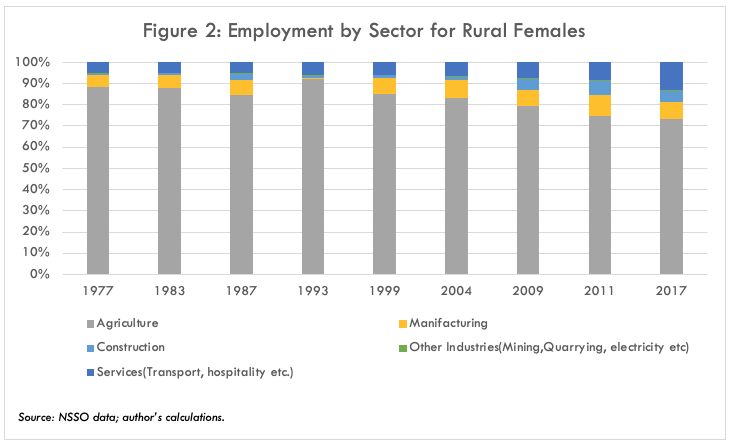

Analysis of NSSO data (1970 – 2018) shows that women have largely been undertaking labor-intensive, home-based, and informal work, concentrated in low-productivity sectors (figures 2 and 3). The proportion of rural women working in agriculture fell from 88.1% in 1977-78 to 73.2% in 2017-18, even as the corresponding decline for rural men was 80.6% to 55% over the same period.

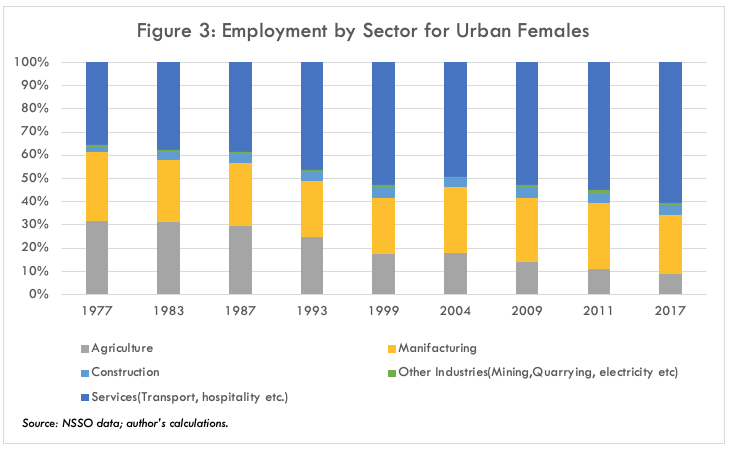

For urban women, the service sector has become increasingly significant, with its share in employment rising from 35.7% in 1977-78 to 60.7% in 2017-18. In this sector, women have become concentrated in professions such as teaching and nursing, which offer only limited scope for career progression. Unlike men, neither urban nor rural woman could significantly increase their presence in the secondary sector.

Chaudhary and Verick (2014) estimate that absolute increase in female employment between 1994 and 2010 largely took place in low growth sectors, such as agriculture, and handicrafts, marked by low productivity and wages. Further, they posit that if women had access to the same work opportunities as men, the absolute increase female employment would have been up to three times higher during this period. Kapsos (2014) found that less than 19 per cent of the new employment opportunities generated in India’s 10 fastest growing occupations were taken up by women. Despite increases in primary and secondary educations, women have systematically lost out on opportunities in fast growing sectors owing to an increasing demand for technically skilled labor, and men having higher tertiary educational and vocational training levels (figure 4).

- Increased mechanization and now automation

The increased mechanization of traditionally labor-intensive tasks across sectors, be it agriculture, manufacturing, mining and now automation in the services sector, has always affected women disproportionately. ADB (2019)’s data analysis between 1968 to 2015 shows that men have traditionally had access to a greater proportion of emerging occupations in India. Mehrotra et. al. (2017) point out that the use of seed drillers, harvesters, and threshers has displaced female workers disproportionately from the workforce. Mckinsey Global Institute (2019) has estimated that up to 12 million Indian women could lose their jobs by 2030 owing to automation in the agriculture, forestry, fisheries, transportation and warehousing sectors. The enduring digital divide and increased automation of clerical job roles can make it difficult for women to transition to jobs requiring higher education and technical skills.

- Rising household wealth leads to women dropping out, as they are considered secondary income earners (the income effect hypothesis)

Rising household wealth fueled by economic growth obviates the financial need for a supplementary income. Kapsos (2014) estimates that this “income effect” (The income effect measures the change in the demand for a good or service as a result of a change in total income) of increased household wealth can explain about 9% of the total decline in female participation in the labor force between 2005 and 2010. NSSO data (1970 – 2018) shows that female worker participation rates are lower for higher expenditure categories, particularly in rural areas. Families take pride when female members withdraw from work, demonstrating that male members can provide a comfortable life for the family. This continued perception of women being secondary earners has also translated into sticky wage differentials such that the female wage has remained about 60-65% of the male wage (on average) over the last three decades (1993-2018). This wage gap perpetuates an incentive structure for men to continue working and women to withdraw when household wealth increases.

- Lack of family support and formal institutional structures

Even today, women in India spend up to 352 minutes per day on domestic work, 577% more than men (52 minutes) (OECD, 2017). Married women have lower LFPRs (Fletcher, Pande and Moore 2017), and amongst rural women, the largest declines in FLFPR over the 1993 – 2018 period are in the below 34-year, child-bearing age categories (NSSO data). The deep-rooted segregation of gender-specific activities further results in a lack of family support for women’s careers and prevents Indian women from participating in the workforce.

Mehrotra et. al. (2017) point out that the lack of facilitating factors – such as flexible work arrangements, institutional support for childcare (e.g. maternity leave, creches) actively contribute to women’s exodus from the labour force. The Maternity Act (Amendment) 2016 places the entire cost burden of women’s leave on employers disincentivising women’s hiring in the formal sector. Further, less than 1% of the government’s budget is allocated for gender related policies, showing the paucity of resources available for policy action.

The way forward: Bringing women back to work

A women’s decision to enter the labour force is deeply influenced by her family, marital, educational and social status. Continuing to work is a daily choice – which is rarely made by women alone. Therefore, to (a) bring more women into the labour force, and (b) prevent them from dropping out of work, there is a need for targeted interventions by all relevant stakeholders – the government, private sector, media and civil society.

Government: Policy actions

- Set course-wise gender-based targets for skill training under Skill India mission, to ensure women’s participation across job-roles to meet industry requirements

- Set quantitive targets to increase access and improve learning outcomes for girls at primary, secondary and tertiary level under the new National Education Policy

- Provide matching grants to micro, small and medium enterprises to finance women’s maternity leave

- Increase quantum of allocation for programs targetted at women under the Gender Budget from the present 1% of GDP

Corporate sector: Re-orient diversity programs

- Expand focus from just having quantitative targets on number of women hired to mainstreaming women across all job roles

- Create consciousness to move away from the notion of certain tasks being a “woman’s job”

Civil society & Media: Influence attitudes and choices

- Encourage women to join schools, vocational training programs; undertake confidence building programs

- Partner with government to execute existing schemes such as Beto Bachao, Beti Padhao; question poor implementation

- Highlight female role models in mainstream media, in schools, colleges and celebrate the success of professional women

Over the last 70 years, women have remained on the margins of the formal economy dutifully supporting doctors as nurses, master weavers as assistants, and farmers as casual agricultural labourers. It is high time women were brought to the frontlines of nation building, and given their fair share of the economic pie.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Another version of this article has appeared on the Times of India, Irrational Economics blog, and can be found here. The author would like to thank co-authors: Poorva Prabhu and Ujjwala Singh; and research assistants: Manvika Gupta and Khyati Bhatnagar. Featured image: Women at work in field. Credit: KML, Pexels.