Social media are a fundamental part of life for a large portion of the population, especially the young. But what does this involvement, where sharing a great deal of personal information is commonplace, mean for people’s views about privacy and freedom of expression? Nathaniel Swigger has investigated the use of social media and views on civil liberties and privacy. He finds that for those under the age of 25 support for freedom of expression rises, and support for privacy falls, as social media involvement increases.

Social media are a fundamental part of life for a large portion of the population, especially the young. But what does this involvement, where sharing a great deal of personal information is commonplace, mean for people’s views about privacy and freedom of expression? Nathaniel Swigger has investigated the use of social media and views on civil liberties and privacy. He finds that for those under the age of 25 support for freedom of expression rises, and support for privacy falls, as social media involvement increases.

Recent months have seen considerable revelations about the extent of spying by government agencies on individuals, prompting new debates about privacy and civil liberties. Even outside of the surveillance revelations, it is clear that in the age of growing social media use, the way that we feel about civil liberties is changing. My recent research looked at whether or not social media behaviors alter the way one thinks about issues like free speech and individual privacy. I found evidence that social media usage plays a role in formulating civic values, but only for people who came of age in an era of social media. The evidence indicates that social media acts like a socializing agent in the same way we would normally think of schools or early childhood experiences. The future may look very different because it will be shaped by generations that have different priorities and concerns regarding civil liberties.

Key to this change, of course, is the change in social norms created by the social media revolution. It is a cliché to suggest that the Internet has changed everything (in fact it may even be a cliché to point out the cliché), but social media and communication technology have ushered structural changes into everyday life. As others have pointed out, social media provide(s) unprecedented opportunity for people. Twenty years ago, few Americans had a forum to share their views or the content of their lives. Now, almost everyone can share themselves with a public audience. Additionally, there is an expectation that they will also be able to learn about other people in the same public environment.

Raise your hand if you’ve met someone in person and then immediately followed up that meeting by looking him or her up on Facebook.

The point is that we have created a social environment where it is commonplace to share lots of information about yourself and access lots of information about other people. To put it in political terms, we increasingly exercise our right to freedom of expression, and increasingly ignore (for both ourselves and others) the right to privacy. For young adults who have been socialized in this new environment, this is the norm. As they experienced adolescence and formed relationships they had as much social activity online as they did in person, and experienced a world where they were expected to engage (e.g. share information) with others on social media sites. At a time when they were still conceptualizing individual rights (like privacy and free expression), they were simultaneously engaged in a virtual world that diminishes the former and emphasizes the latter.

To investigate the relationship between social media and support for civil liberties, I used an Internet sample provided by Qualtrics, Inc, where 913 Americans answered questions that pitted concerns for individual rights against concerns about security. For example, respondents were asked if they agreed more with the statement, “Government should be allowed to record telephone calls and monitor email in order to prevent people from planning terrorist or criminal acts,” or, “People’s conversations and email are private and should be protected by the Constitution.” The survey included 3 items on privacy, and 2 on freedom of expression. The survey asked about individuals’ frequency and type of activity on sites like Facebook and Twitter, as well as other items to capture individual personality and general political views. I combined the social media measures into a single index from 0-1 and combined civil liberties items into scales from -3 to 3 (for privacy) and -2 to 2 (for freedom of expression).

Using these measures I found a significant effect for social media for both freedom of expression and privacy. The coefficient for social media is significant and negative when privacy is the dependent variable and significant and positive when freedom of expression is the dependent variable. But this is only true when dealing with participants age 25 and under, people who experienced adolescence after the rise of social media. Even after controlling for personality traits and political ideology, there is still a significant relationship between social media activity and support for civil liberties among young adults. Those who grew up in an age of social media and actively engaged in those online activities are much more supportive of free expression and much less supportive of privacy rights.

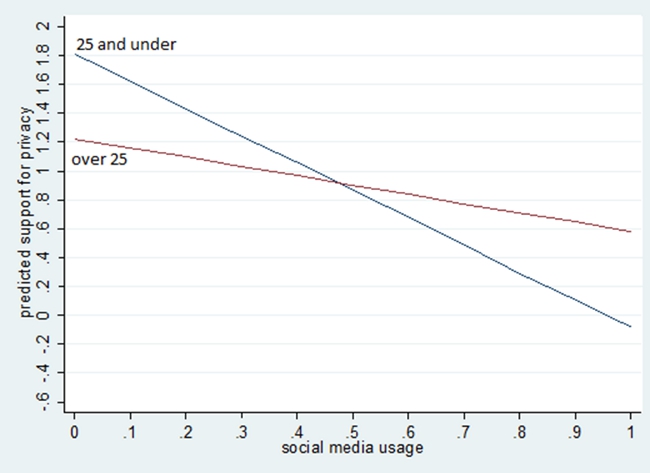

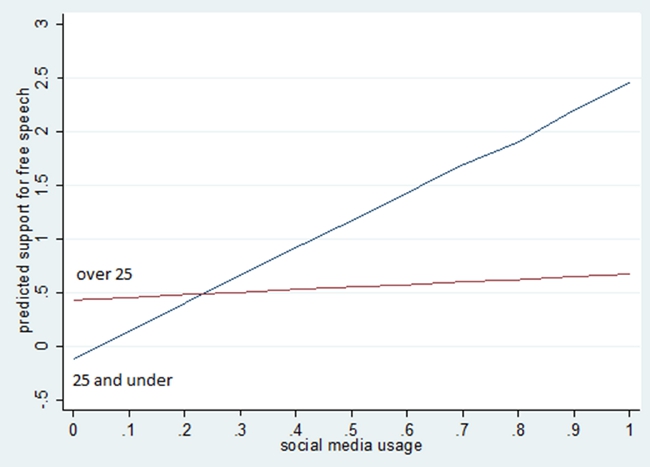

In order to show the magnitude of these effects I used the results from modeling to generate predicted values based on increasing levels of social media use. Figure 1 shows the change in predicted support for privacy as social media use increases. For younger respondents, increase in social media use from low to medium moves the average respondent about 1 point on the scale. As a younger respondent uses social media even more his or her predicted support for privacy actually drops below 0. The size of the effect of using social media is actually comparable to the effect of fear of terrorism. In contrast, among older respondents support for privacy declines as well, but not to a statistically significant degree. The effect on support for free expression, as seen in Figure 2, is also substantial with a 3 point increase in predicted support as social media use increases.

Figure 1 – Age and support for privacy by social media use

Figure 2 – Age and support for free speech by social media use

The data indicates that if you came of age in the new world of social media, you likely developed different priorities about privacy and expression. In the future we should expect trends like this to continue. Technology has advanced to being so heavily integrated into our lives that there is every reason to believe that it will influence our behavior, our perspectives, and our values. If technology can change views on civil liberties, what else will the new social media norms bring?

This article is a shortened version of “The Online Citizen: Is Social Media Changing Citizens’ Beliefs About Democratic Values?” in Political Behavior.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/16vHHlX

_________________________________

About the author

Nathaniel Swigger –The Ohio State University

Nathaniel Swigger –The Ohio State University

Nathaniel Swigger is an Assistant Professor, at the Newark campus of The Ohio State University. His research and teaching interests are American politics with emphasis on public opinion, political psychology, campaigns and elections, and media analysis. His current research focuses on emotional and rational responses to campaign advertising, and inter-generational differences in attitudes toward civil liberties and democratic values.

1 Comments