Since 1996, local police departments in the U.S. have gained the power to enforce immigration policies, so that local police may now check arrestees and other persons they encounter for possible immigration violations. Using survey data from police executives of 237 cities, Paul G. Lewis, Scott H. Decker, Doris Marie Provine, and Monica W. Varsanyi have closely examined how police departments now enforce immigration policies at street level. They find that police practices tend to reflect policy priorities, if they have been set out clearly, and that Hispanic police chiefs and elected officials are associated with lessened enforcement. They argue that many police departments develop ad hoc strategies to deal with potential unauthorized immigrants, or simply leave key decisions up to the discretion of individual officers.

Since 1996, local police departments in the U.S. have gained the power to enforce immigration policies, so that local police may now check arrestees and other persons they encounter for possible immigration violations. Using survey data from police executives of 237 cities, Paul G. Lewis, Scott H. Decker, Doris Marie Provine, and Monica W. Varsanyi have closely examined how police departments now enforce immigration policies at street level. They find that police practices tend to reflect policy priorities, if they have been set out clearly, and that Hispanic police chiefs and elected officials are associated with lessened enforcement. They argue that many police departments develop ad hoc strategies to deal with potential unauthorized immigrants, or simply leave key decisions up to the discretion of individual officers.

What happens when the federal government devolves immigration enforcement — historically a national responsibility – to the local level? Our research suggests one answer: a patchwork of often contradictory responses by local police and city governments, responses that do not necessarily further national goals. Using data from a national survey of police chiefs in US cities, we sought to explain this pattern of local policy choices and police practices.

Many local police departments in the US feel pressure to get involved in immigration enforcement. The pressure comes both from state and local governments that have passed legislation authorizing or requiring local police to enforce immigration law, and from Congress, which in 1996 enabled new enforcement and intelligence roles for local police, roles that formerly had been the province of federal immigration authorities. The Anti-terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act gave local police authority to arrest previously deported non-citizen felons, and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act envisions state and local police as “force multipliers,” authorizing them to enforce federal immigration laws. The Obama Administration has reframed these efforts with “Secure Communities,” a program that relies on local jail officials to check arrestees for possible immigration violations during the booking process.

Local police have reacted to these changes in various ways. Some have developed on-going relationships with federal immigration agents, while a small percentage have signed formal agreements to engage in immigration enforcement under the federal “287g program.” Other local governments and police departments have moved in the opposite direction. A relative handful have adopted “limited cooperation” ordinances, designating themselves as sanctuary cities, while others follow a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy when interacting with undocumented immigrants.

We examined four factors that might shape local responses to unauthorized immigrants: rapid demographic change and the perceived “threat” from new immigrants; proximity to national land borders; political context and lines of authority between elected officials and police; and organizational characteristics of the police department itself.

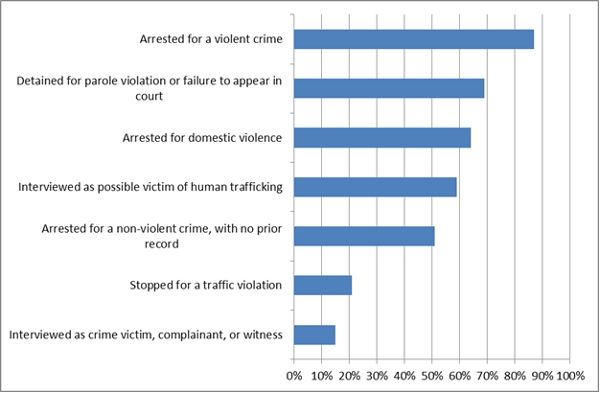

Our study was unique in examining what police departments actually do in everyday patrol and investigation activities. We considered seven scenarios (e.g. a traffic stop, a parole violation), asking police chiefs whether in that situation their officers would check immigration status or contact federal immigration authorities – or both (see Figure 1). We received survey responses from more than half of police departments in cities with populations of 65,000 or higher.

Figure 1 – Police response when encountering a suspected unauthorized immigrant

Note: This chart, organized in de-escalating order by how serious the scenario is, indicates the share of police chiefs who said that their officers would check the individual’s immigration status or report the individual to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials.

We found that where a city’s elected officials have established clear policy priorities, these priorities are indeed reflected by police practices. In cities that have passed enforcement-oriented immigration policies, for example, police tend to respond to immigration violations more aggressively. Perhaps surprisingly, neither the “demographic threat” of a rapid influx of immigrants, nor the city’s rate of violent crime, nor its level of unemployment is associated with police enforcement practices.

Factors internal to police agencies, on the other hand, do appear to influence the level of enforcement. Police departments with a written policy regarding racial profiling tend to be less punitive in immigration enforcement. A Hispanic police chief is an even more significant factor associated with lessened enforcement. Similarly, city governments with one or more Hispanic elected officials were less likely to have passed enforcement-oriented policies. These results suggest that efforts to make city governments and police departments more broadly representative and more aware of the potential for racial bias are not merely cosmetic; they have real-life consequences.

Location matters too. Cities close to the Mexican border are significantly more likely to be enforcement oriented. This may be because the immigration issue is more salient and controversial in these places, or because the presence of the U.S. Border Patrol encourages enforcement-oriented policies. Yet cities located near Canada show the opposite relationship. Rather than making immigration enforcement a priority, most (65 percent) simply have no policy on this topic (as compared to 45 percent in the rest of our sample).

A city’s political leanings also influence law-enforcement practices. Although predominantly Republican cities did not differ significantly from more Democratic communities in their official policies toward immigrants, “street-level” enforcement by police on patrol (as reported by police chiefs) was heavier in Republican-leaning cities. Interestingly, this tendency was only apparent in cities where elected officials have the power to hire and fire police chiefs and other appointees – that is, where police departments are more directly exposed to local political pressures.

Nearly half of the cities we surveyed have no clear local government policy regarding immigration policing – a tendency that is even more pronounced in the smaller communities we subsequently examined. This means that police departments either develop ad hoc strategies for dealing with possible unauthorized immigrants, or leave decisions about such interactions to the discretion of individual police officers. Many key decisions about how police should deal with violations of immigration law are apparently taking place on the street, during the day-to-day encounters between police and immigrants. Thus, neither the national government, nor local elected officials, nor police executives have clear and consistent control over the enforcement activities now taking place. The patchwork that is immigration enforcement, in short, can reach to the level of the individual officer on patrol.

This article is a version of a paper that appeared in the Journal of Public Administration and Theory.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1bFCdJu

_________________________________

About the authors

Paul G. Lewis – Arizona State University

Paul G. Lewis – Arizona State University

Paul Lewis is Associate Professor in the School of Politics and Global Studies at Arizona State University. He is interested in the determinants and effects of public policies, and the way people think about policy. He is the author of two books and many articles on topics related to local government, urban development, and community change in the United States.

_

Scott H. Decker – Arizona State University

Scott H. Decker – Arizona State University

Scott Decker is Foundation Professor and Director of the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Arizona State University. His primary areas of research are in gangs, the offender’s perspective and crime control policy.

_

Doris Marie Provine – Arizona State University

Doris Marie Provine – Arizona State University

Doris Marie Provine is Professor Emerita of Justice Studies at Arizona State University. Her scholarly interests focus on immigration, law, and race. Most recently she co-edited Law and the Quest for Justice (Quid Pro Quo, 2013). She is also the author of Unequal Under Law: Race and the War on Drugs (University of Chicago Press, 2007).

_

Monica W. Varsanyi – CUNY

Monica W. Varsanyi – CUNY

Monica Varsanyi is Associate Professor of Political Science at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York, and a member of the Doctoral Faculty in Geography at the CUNY Graduate Center. Her research and teaching interests include immigration law and policy and urban politics. Her edited volume, Taking Local Control: Immigration Policy Activism in U.S. Cities and States was published by Stanford University Press in 2010.