As political participation continues to decline, how can we encourage citizens to re-engage with politics and voting? One area that has seen participation increasing is membership in political interest groups. Using survey data from 1,071 individuals’ contacts with Congress, Thomas T. Holyoke examines the role of interest groups in stimulating political action and participation. He finds that many groups help to increase, or at least direct, their members’ political participation, so that those who are members of both political and professional interest groups have a greater than 60 percent chance of contacting Congress.

As political participation continues to decline, how can we encourage citizens to re-engage with politics and voting? One area that has seen participation increasing is membership in political interest groups. Using survey data from 1,071 individuals’ contacts with Congress, Thomas T. Holyoke examines the role of interest groups in stimulating political action and participation. He finds that many groups help to increase, or at least direct, their members’ political participation, so that those who are members of both political and professional interest groups have a greater than 60 percent chance of contacting Congress.

Political representation requires participation. It requires citizens to tell their elected lawmakers what they want, to make sure lawmakers respond to their demands with public policy, and to protest when they do not. Unfortunately, most political participation in the United States declined in the twentieth century. Today barely half the electorate vote in presidential elections and less than half bother to turnout for mid-term elections. More voters are abandoning the two major political parties, and minor third parties remain extremely minor. But there is one place where participation is apparently increasing: membership in political interest groups. The 2011 directory Washington Representatives, compiled by Lobbyists.info, lists well over 8,000 interest groups lobbying just the national government, an increase of roughly 2,000 from 1981. But do more interest groups mean more citizen participation? Yes, but only some interest groups stimulate participation; others simply make it easier for politically inclined people to participate.

Modeling Individual Political Activity

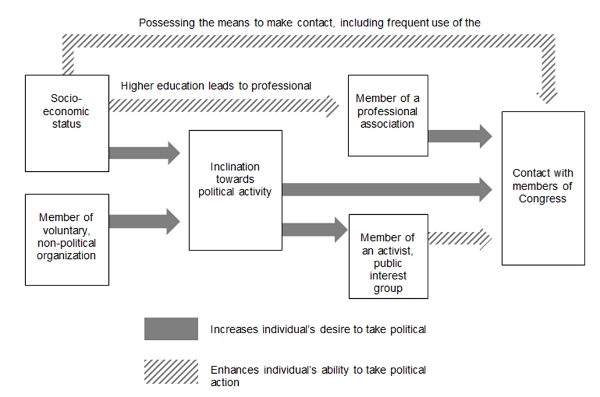

Understanding how and why people participate in politics is difficult. To keep it manageable, I focused on contact with members of Congress, people calling or writing their elected officials to compliment them on their work or, more likely, to complain about it. Figure 1, below, shows a way people might become more inclined towards political contacting (gray arrows) and how their contacting might be facilitated (striped arrows). People of higher socio-economic status should be more inclined towards political activity because they better understand political issues and the consequences if lawmakers make policy that fails to reflect their interests. They are also more likely to have the time, money, and resources to easily contact Congress. Also, people who are active in non-political organizations, like churches, social clubs, and volunteer organizations, are more likely to learn the value of organization as a civic skill and will thus be predisposed to becoming politically active. Even many people of lower socio-economic status find time to participate in churches and philanthropic organizations, thus learning the kinds of civic skills that increase their inclination towards political action.

Figure 1 – Representation of Individual Interest Group Membership and Contact with Congress

Politically inclined people are also likely to join interest groups. But not just any kind of group, they tend to be attracted to the ideologically-driven, cause-oriented groups trying to enact significant changes in policy, or vigorously defend existing policies. These are groups like National Rifle Association, Sierra Club, and National Organization for Women. Because these groups attract people already full of political passion, membership does not stimulate their political participation. The groups merely point already politically-active people in productive directions, making it easier for them to write, e-mail, call, or angrily go see their representatives in person.

It is less politically inclined people who need to be prodded into political action by interest groups, people who join for reasons other than a chance to be politically active. Many professionals must be members in and licensed by their trade associations, like lawyers in bar associations. But professional associations are still interest groups and they still need to influence Congress in the interests of the profession they represent. To that end they often try to motivate their non-political members to participate in politics, perhaps by flying them out to Washington, DC to meet legislators on the association’s annual lobby day. These are the interest groups that stimulate their members’ interest in political participation.

For people who know how, the Internet might make it easier for people to contact Congress in place of interest group membership, though there is no real evidence that using the Internet makes people more politically aware. Somebody surfing the Internet might see a webpage complaining about something Congress did (true or not) and provide a link to another page where angry notes can be quickly sent to Congress (and your personal information quickly sold to third parties). People of lower socio-economic status (SES), however, do not have the same convenient access to the Internet as do people of higher SES. Membership in public interest groups thus compensates people of lower SES, giving them the political knowledge and ability to easily contact members of Congress they otherwise lack. It may be interest groups, not the Internet, that are the political equalizers in American society.

Evidence and Reflection

Is there any evidence that these hypothesized connections between citizens and Congress exist? To find out I used data on citizen contact with Washington legislators from a 2007 survey of 1,071 individuals by the Congressional Management Foundation for a series of reports on citizen contact with Congress. Respondents were asked a battery of questions regarding their inclination towards political activity (on a scale of 0 to 5), socio-economic status, membership in interest groups and non-political clubs, familiarity with the internet (a scale of 0 to 6), and whether they had contacted a member of Congress in the last year.

The data largely confirms the connections in Figure 1. Take socio-economic status influencing political inclination. One SES measure was education, and 59 per cent of respondents with a higher than average level of political inclination (scale average is 2.43) have college degrees. Another measure was annual income – 66 per cent of respondents with higher than average political inclination scores also have an income greater than $50,000, and 46 per cent more than $75,000. Social organization membership also contributes to political inclination, 27 per cent of respondents reporting they joined a club (or renewed membership) in the last five years have average political inclination scores of 3 while those who do not have average scores of 2.

For the 61 per cent of respondents belonging to a political interest group, 43 per cent belong to cause-oriented public interest groups, 30 per cent belong to a professional association, and 18 per cent to both. Public interest group members have an average political inclination score of 3, while professional and trade association members’ average score is 2.2. However, while 62 per cent of respondents in a public interest group contacted Congress, 67 per cent of people with a higher than average political inclination also did so, but since highly politically inclined people tend to join public interest groups, this means there is no clear evidence that group membership per se leads to high levels of contacting. By contrast, 68 per cent of individuals in professional associations contacted Congress, and since their average level of political inclination, and thus their independent likelihood of contacting Congress, is lower, there is evidence here that interest group membership is stimulating their political participation.

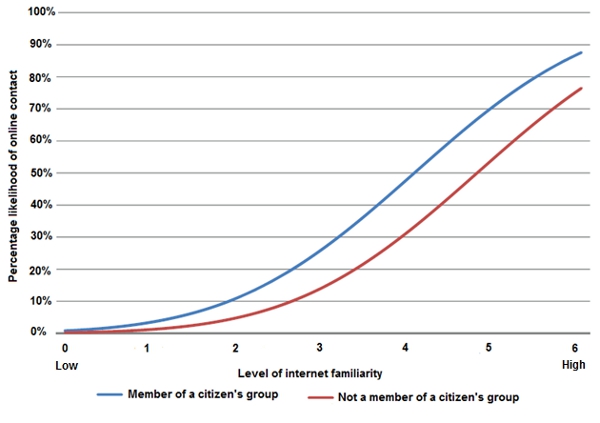

About 57 per cent of respondents with higher than average scores on the Internet familiarity index contacted Congress, but only 39 per cent of those with below average scores did so. Since the data reveals no real correlation between Internet familiarity and interest group membership, especially membership in public interest groups, it may be true that membership in such groups really is compensating members for their lack of Internet familiarity. As Figure 2 below illustrates, the increase in the likelihood of electronic contact for citizen group members increases more quickly than for non-members with even small increases in Internet familiarity. The implication is that if members have just a little experience with the Internet, the organization compensates them for the rest, making it easier to fulfil the desire to make contact.

Figure 2 – Likelihood of online contact by group membership and Internet familiarity

So some interest groups, specifically the professional associations, really do appear to increase member political participation. Others, especially the politically-charged public interest groups, do not stimulate participation so much as direct it, helping members know how best to use their political passions, and making it easy for them to vent their frustrations at members of Congress. Whether or not the issues these interest groups push members to complain to Congress about are really in these members’ interests, however, is another matter entirely, but one even more crucial for assessing the quality of representative democracy.

This article is a version of the paper ‘The interest group effect on citizen contact with Congress’ published in Party Politics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1bY7pnI

_________________________________

About the author

Thomas T. Holyoke – California State University

Thomas T. Holyoke – California State University

Thomas T. Holyoke is associate professor of political science at California State University, Fresno. He specializes in interest groups and lobbying in Washington, DC, as well as education policy and western water politics. He has published in journals such as American Journal of Political Science, American Journal of Education, and Political Research Quarterly. He is the author of the book Competitive Interests: Competition and Compromise in American Interest Group Politics (2011, Georgetown University Press) and the forthcoming book Interest Groups and Lobbying: Pursuing Political Interests in American Politics (2014, Westview Press).