The gender integration of the U.S. Armed Forces has been an ongoing process since the establishment of the All-Volunteer Force in 1973. In light of the removal of the ban on women in direct-combat positions, Saskia Stachowitsch examines the changing media depictions of military women, arguing that these representations vary with the military’s need for female soldiers, as well as geopolitical conditions.

The gender integration of the U.S. Armed Forces has been an ongoing process since the establishment of the All-Volunteer Force in 1973. In light of the removal of the ban on women in direct-combat positions, Saskia Stachowitsch examines the changing media depictions of military women, arguing that these representations vary with the military’s need for female soldiers, as well as geopolitical conditions.

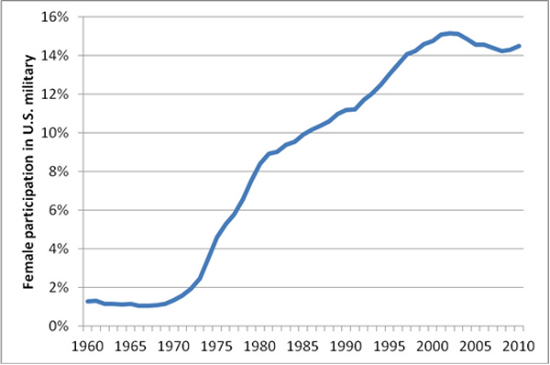

The US Department of Defense has recently announced to remove its ban on women in direct ground-combat positions. For the 214,098 women (14.6% of active duty personnel) in the US Armed Forces, this signifies an important step towards full integration – a process which has stagnated since the early 1990s, when combat positions in naval and aerial warfare as well as ground-combat support units were opened.

Looking at articles dealing with military gender issues from 1990 to 2010 in the American daily newspapers The New York Times and The Washington Post has shown that the image of military women has varied greatly throughout the integration process, ranging from portrayals of female service members as ‘efficient professionals’ and ‘patriotic heroines’ to ‘beautiful souls’ in need of protection and sexualized ‘misfits’ in a male domain. How women were portrayed depended strongly on recruitment environments, but also on (geo)political conditions.

Professionalization and modernization have been the main driving forces behind gender integration in the US military. In the All-Volunteer Force, established in 1973, more qualified specialists were needed than the male workforce alone could provide and this increased the military’s dependency on female labor. Due to gender discrimination in the civilian sector, women also provided a low cost personnel reserve to make up for the loss of male conscripts. Integration gained momentum after the end of the Cold War, when personnel were downsized, but qualification requirements kept rising due to the technologization of warfare. This led to comprehensive equality measures and increased female participation to 14.5 % by 1999, compared to just 2% in 1972, as Figure 1 illustrates.

Figure 1 – Female participation in U.S. military 1960-2010

Exclusions were, however, upheld and limited women to those jobs for which not enough qualified male personnel were available, particularly in specialized non-combat support jobs on lower and middle ranks. This curtailed women’s career prospects and has also been linked to the high levels of sexual abuse within the ranks.

Structural change profoundly affected military gender images, which transcended the dualism of ‘war-prone men’ and ‘peaceful women’. Institutional modernization promoted media depictions of women as capable service members and a gender-neutral definition of military professionalism became increasingly accepted. At the same time, the selectivity of integration was mirrored in diversified notions of military gender roles, promoting a progressive view of women’s suitability for some tasks, while referring to traditional stereotypes to justify exclusions from others, such as ground-combat and leadership.

Positive images of women in the services were particularly pronounced during times of increased dependency on female labor and when it served the positive portrayal of an ongoing overseas military intervention. In the early 1990s, for example, military women were overwhelmingly portrayed as professional soldiers in a technologically advanced military with focus on effectiveness and gender-neutral performance standards. The lack of qualified specialists in an increasingly high-tech military and the relatively high participation and visibility of military women during the Persian Gulf War supported these trends.

When dependency on the female workforce decreased and competition for military jobs was greater, negative images prevailed in media depictions. Consequently, by the late 1990s, women were mainly depicted as sexualized intruders and as symbols of ‘unheroic’ warfare. Their integration was constructed as an antithesis to traditional military values and a symptom of military and national decline. This was at a time when the implementation of legal changes led to a rise in female representation while many (male) jobs were being cut. The loss in status which parts of the military elite and the more traditionally organized occupational fields experienced in the course of modernization were thus interpreted as ‘feminization’.

After 2000, portrayals became more positive again, but this time faith, heroism, and patriotism were more dominant themes than professionalism and competence. An integrated military was depicted as a strategic and moral advantage in the ‘war on terror’. A growing number of articles suggested that the military should utilize traditional gender stereotypes, e.g. by showcasing female soldiers as non-threatening and peaceful to win ‘hearts and minds’ of the civilian population. Military growth and strategic changes (smaller fast-deploying force, flexible units, stationing of support with combat troops) increased the necessity for flexible deployment of the female workforce and fostered these positive, if ambivalent images.

This trend continued into the 2010s, but new images were added: women were more frequently depicted as tough and resilient, as competent leaders, and trustworthy comrades on the battlefield. Increased dependency on women, also in combat positions, and the bureaucratic problems that legal exclusions raised for commanders in a long and arduous deployment provided the military background for this.

Though recruitment conditions and strategic factors were important in the formation of military gender images, they did not translate one-to-one into media representations. Domestic and global political power relations were equally relevant. The Clinton administration, for example, modernized military gender relations after the end of the Cold War; the Democratic majority in Congress enabled the enforcement of these initiatives. This favored positive portrayals of military women and gender integration. After the ‘Republican revolution’ in 1994/95 opponents were on the rise again, leading to more negative attitudes towards gender equality in the services.

While the strategic vision of the Bush Jr. administration depended on women’s military participation, conservative gender policies in the civilian realm promoted stereotypical portrayals. Women’s integration was not reversed, but institutionally and discursively disconnected from equality agendas. More progressive images again appeared in the context of Obama’s reforms of military gender policy, such as reinstating the availability of abortions at military hospitals and bases, the abolishment of the ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ policy, and the repeal of ground-combat exclusion.

Foreign policy contexts mattered as well; the United States’ new geopolitical position after the Cold War fostered their self-representation as a role model for emancipation and gender equality. Military doctrines began to prominently feature women’s rights and protection from sexualized violence as rationales. The UN Security Council, NATO, and other international organizations mainstreamed gender into their peacekeeping and post-conflict reconstruction projects on the basis of an assumed link between gender relations and international security.

In this context, equality in the services was tied to the objectives of interventions in the Arab world. The narrative of ‘liberating oppressed Muslim women’ was already relevant during the Persian Gulf War, but became even more influential during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The alleged freedom and equality of US service women was contrasted with the ‘misogynist enemy’.

While the most problematic gender ideologies associated with the ‘war on terror’ have been removed from military doctrines, new measures, such as the establishment of all-women Female Engagement Teams in Afghanistan, still utilize stereotypes of women as peace-makers and proof of US ‘cultural sensitivity’ – a strategy that puts gender equality at the service of militarization.

This article is based on Professional Soldier, Weak Victim, Patriotic Heroine in the current issue of the International Feminist Journal of Politics and the book Gender Ideologies and Military Labor Markets in the US, (Routledge, 2012)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1brnJ2f

_________________________________

Saskia Stachowitsch – University of Vienna

Saskia Stachowitsch – University of Vienna

Saskia Stachowitsch is a post-doctoral research fellow and lecturer at the Department of Political Science at the University of Vienna. Her areas of research are gender and the military, private security, and feminist international relations.