The oversight and review of government agencies is an important part of Congress’ function. But can this oversight become so complex that it actually reduces the influence of Congress over policymaking in the federal bureaucracy? Using a survey of more than 2,000 government executives, Joshua Clinton finds that the more Congressional committees that are involved in agency oversight, the more empowered the president is compared to Congress. He writes that this may stem from a tendency for some committees to ‘free-ride’ off of the efforts of others, and divisions across committees over what they wish the agency to do.

The oversight and review of government agencies is an important part of Congress’ function. But can this oversight become so complex that it actually reduces the influence of Congress over policymaking in the federal bureaucracy? Using a survey of more than 2,000 government executives, Joshua Clinton finds that the more Congressional committees that are involved in agency oversight, the more empowered the president is compared to Congress. He writes that this may stem from a tendency for some committees to ‘free-ride’ off of the efforts of others, and divisions across committees over what they wish the agency to do.

Following the creation of the Department of Homeland Security, in 2004 the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (also know as the 9/11 Commission) urged that “Congress should create a single, principal point of oversight and review for homeland security” to ensure that Congress would be able to most effectively oversee the actions of this powerful and important new agency. Congress ignored this advice, however, and created instead a situation of overlapping jurisdictions in which, at one point, more than 108 committees and subcommittees had oversight responsibilities related to the agency.

While the desire of individual members to be involved in agency policymaking and have a say on one of the most important issues confronting the country is perhaps understandable from the electoral perspective of individual members of Congress, we have found that such a complicated arrangement affects the ability of Congress as a whole to compete with presidential influence when attempting to direct policymaking in the federal bureaucracy.

While measuring political influence over an agency is admittedly a difficult task, we were able to use survey responses from 2,225 appointed and career executives responsible for implementing and administering the programs of the federal bureaucracy in 2007 and 2009, to assess the extent to which members of Congress and the presidency influence agency policymaking.

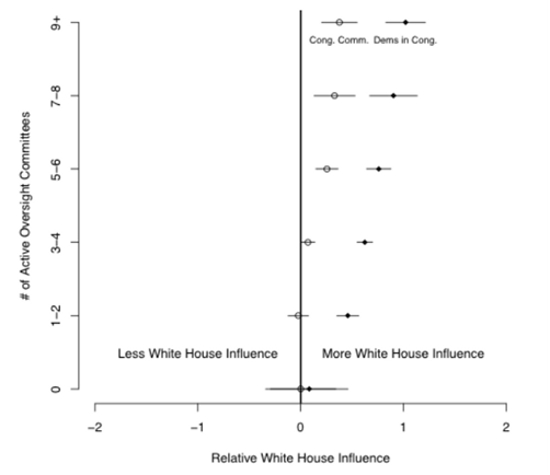

The basic result is immediately evident when we consider how the relative influence of the White House and Congress changes as the number of committees exercising active oversight increases according to the surveyed executives. Figure 1 below shows that as the number of congressional committees involved in overseeing an agency increases, the advantage of the White House over Congress grows in the opinion of the surveyed executives. This is true if we look at congressional influence in general or at the influence of the then-majority party Democrats.

Figure 1: Relationship between Influence and Congressional Committee Oversight.

Source: Based on Responses of career executives to the 2009 Survey on the Future of Government Service.

Employing more complicated statistical models to control for the possibility of biased perceptions and which also can account for important differences in agency function and structure that may affect the relative influence of the two branches does not appreciably change the conclusion evident from the pattern in Figure 1– the more committees that are involved, the more empowered the president is relative to Congress.

Why might this be? Two explanations for this finding seem plausible, though it is difficult for us to determine which is most responsible given the data available to us. First, it may be that as the number of committees involved increases, the incentive to “free-ride” off of the supposed efforts of other committees increases. That is, if many congressional committees are involved in overseeing an agency, each committee may be reluctant to do the time-consuming work associated with overseeing the agency on a routine basis given that other committees would benefit from such efforts without having to do the work. Second, as the number of committees involved increases, it may be that the committees are increasingly divided on what they want the agency to do. In contrast to a president who can speak with a single voice, the chorus of interests in Congress may adversely affect the ability of Congress to articulate a clear policy directive or response. These interpretations of the relationship are admittedly speculative, but they help highlight why a single congressional committee was originally thought to be optimal for overseeing the Department of Homeland Security — as the number of involved committees increases not only does it become harder to coordinate action because of the number of individuals involved, but it also may become more likely that the individuals involved disagree.

What is optimal for the re-election efforts of an individual member of Congress may not be optimal for the institution of Congress as a whole. Our research into the ability of Congress to oversee a bureaucracy when confronted with a president from the opposite party suggests that congressional influence relative to the president decreases as more committees become involved in the process. If so, increasing the number of committees with access to an agency may simultaneously increase the ability of members to secure electorally valuable outcomes for their constituents while undermining the ability of Congress as an institution to respond collectively to the actions of the presidency or the bureaucracy. How this tension is resolved has important implications for the ability of the legislative branch to compete with the president in shaping the implementation of policy in the United States.

This article is based on the paper Influencing the Bureaucracy: The Irony of Congressional Oversight, in the American Journal of Political Science.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1a79grG

_________________________________

Joshua Clinton – Vanderbilt University

Joshua Clinton – Vanderbilt University

Josh Clinton is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at VanderbiltUniversity. He uses statistical methods to better understand political processes and outcomes. He is interested in: the politics in the U.S. Congress, campaigns and elections, the testing of theories using statistical models, and the uses and abuses of statistical methods for understanding political phenomena.