With more than 2 million citizens incarcerated, the United States currently has the largest prison population in the world. Although more than 1.7 million children currently have a parent behind bars, the actual effects of imprisonment on families are not well understood. Drawing on her current research, Kristin Turney challenges the notion that male incarceration is universally negative for families, painting, instead, a complicated picture of how fathers’ imprisonment impacts family relationships.

With more than 2 million citizens incarcerated, the United States currently has the largest prison population in the world. Although more than 1.7 million children currently have a parent behind bars, the actual effects of imprisonment on families are not well understood. Drawing on her current research, Kristin Turney challenges the notion that male incarceration is universally negative for families, painting, instead, a complicated picture of how fathers’ imprisonment impacts family relationships.

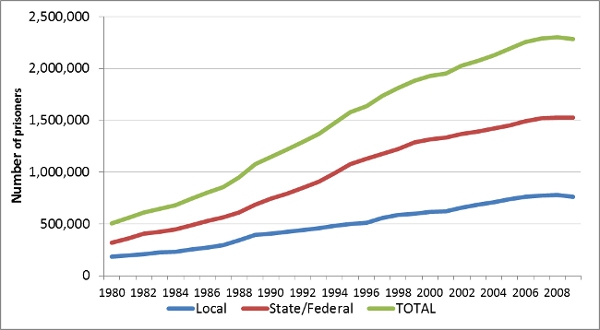

The American incarceration rate has increased dramatically in the past four decades, meaning more and more families have been or are affected by the incarceration of a loved one. More than 1.7 million children currently have a parent imprisoned in state or federal prison, while even more have a parent in local jails. Parental incarceration is especially concentrated among poor and minority families; more than 25% of black children, and 50% of black children whose fathers do not have high school degree, will experience paternal incarceration by age 14.

In response to the growing number of families and children affected by incarceration, especially paternal incarceration, researchers across an array of social science disciplines (e.g., sociology, economics, political science) have been considering how incarceration affects various aspects of family life. To date, most research postulates almost universally negative effects of male incarceration on the affected families. However, the results of my recent research, forthcoming in the American Sociological Review, show that the effects of incarceration on family life are actually quite complicated.

Figure 1 – US Prison Population, 1980 – 2009

Source: Felon Voting

In this study, co-authored by Christopher Wildeman of Yale University, we examine how paternal incarceration affects three aspects of family relationships: fathers’ parenting, mothers’ parenting, and the relationship between parents. We use broadly representative data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, a nine-year longitudinal study of mostly unmarried parents who gave birth in 1998 and 1999. Nearly half of the fathers in this study were incarcerated before their child’s ninth birthday, and these incarcerated fathers have demographic characteristics that are similar to those of fathers incarcerated in local jails, state prisons, and federal prisons.

Our analyses of the relationship between paternal incarceration and family life yield five conclusions that, taken together, begin to show the complicated nature of these relationships. First, we find that when parents live together prior to the fathers’ confinement, fathers who have been incarcerated recently (defined here as in the past two years) exhibit fewer favorable parenting behaviors compared to their counterparts who have not been incarcerated. After being released from prison or jail, these recently incarcerated fathers engage less with their children and co-parent less with their children’s mothers.

Second, for fathers not living with their children prior to incarceration, we find that imprisonment has no causal effect on their parenting after release. Recently incarcerated non-residential fathers do spend less time with their children and engage in less co-parenting with their children’s mothers than their counterparts, but these fathers were also less engaged parents prior to their incarceration. Following this, it seems as though these men would be less involved with their children regardless of their time spent in prison.

Third, we find that most of the observed negative effects on fathers’ parenting do not result directly from the incarceration experience, but indirectly from changes in fathers’ relationships with their children’s mothers. Our findings are consistent with those of other researchers who have found that incarceration has deleterious effects on romantic relationships. Imprisonment destroys fathers’ relationships with their children’s mothers, by facilitating separation, reducing relationship quality, and decreasing mothers’ trust in fathers. In turn, these post-incarceration changes in the relationship lead to reductions in fathers’ parenting.

Fourth, although we find that incarceration is detrimental to fathers’ parenting—at least among fathers who were living with their children prior to their confinement—we find no evidence that paternal incarceration has a causal effect on mothers’ parenting. Mothers who share children with recently imprisoned fathers spend similar amounts of time with their children to those who do not have recently incarcerated partners and report similar levels of parenting stress. This is true of both mothers who were, and were not, residing with fathers immediately prior to his incarceration. There is even some evidence that these mothers increase the time they spend engaging with their children, suggesting that mothers compensate for the loss in fathers’ involvement.

Lastly, we find that paternal incarceration does affect mothers in other ways. Mothers who share children with recently incarcerated fathers are likely to separate from these men and move on to new partners. This re-partnership may have positive or negative effects on children; it may offset some losses in the involvement of the biological father, but simultaneously it leads to greater family complexity for children.

Overall, these findings have important implications for social policy. Policymakers should be aware that incarceration, especially when men are living with children prior to their incarceration, represents a substantial barrier to involvement in parenting after release. Policymakers should strive to keep children and fathers connected during the confinement period, which may have benefits for children and for fathers as family contact is important to the reintegration and rehabilitation process. Policymakers and researchers should also be attentive to complex, often countervailing ways, that incarceration affects different individuals in the family.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: bit.ly/1dRpKEs

_________________________________

Kristin Turney – University of California, Irvine

Kristin Turney – University of California, Irvine

Dr. Kristin Turney is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Irvine, and a faculty affiliate at the Center for Demographic and Social Analysis (C-DASA). Broadly, her research examines the transmission of social inequality between and within generations. More specifically, her research interests include the collateral consequences of incarceration for family life, the effects of depression on individuals and children, and the causes and consequences of childhood health inequalities. These substantive interests are accompanied with a methodological interest in causal inference.