In recent months, much has been written about the level of political polarization in America, and the lack of political competition in many states. By surveying over 24,000 voters, Phil Jones gives further reason why political competition is important – states with greater political competition have greater levels of voter knowledge of, and responsiveness to, congressional representation. He also finds that unrepresented voters will only tend to desert the incumbent in competitive races, giving legislators in uncompetitive districts greater leeway to shirk from public opinion in making policy decisions.

In recent months, much has been written about the level of political polarization in America, and the lack of political competition in many states. By surveying over 24,000 voters, Phil Jones gives further reason why political competition is important – states with greater political competition have greater levels of voter knowledge of, and responsiveness to, congressional representation. He also finds that unrepresented voters will only tend to desert the incumbent in competitive races, giving legislators in uncompetitive districts greater leeway to shirk from public opinion in making policy decisions.

Despite the United States being a diverse and politically competitive nation, most legislators represent uncompetitive constituencies. For example, the most recent Rothenberg Political Report/Roll Call ratings of 2014 House races categorize just six of the 435 contests as true “toss-ups”. While many scholars are rightly worried about how this lack of competition might affect politicians in Congress, few have considered how it affects the ways in which voters hold their representatives to account. In recent research, I show that what voters know about their US senators’ policy record, and how they factor it into their vote choice, is directly linked to the general level of political competition in their state.

While I have measured competition in several ways, here I focus just on margins of victory in previous statewide elections. I calculated the average margin of victory for winners in several electoral cycles, and subtracted that number from 100. Lower scores thus indicate less competition, higher scores greater competition on average. These state-level variables are linked to data from the 2006 Cooperative Congressional Election Study, which surveyed around 24,000 voters in states with incumbent senators running for re-election. Respondents were asked for their own position, and whether they knew the position of their senator, on seven high profile bills in Congress, ranging from a ban on “partial birth” abortion to increasing the federal minimum wage.

These survey questions allow us to assess the number of roll call votes on which constituents correctly identified their senator’s position. Controlling for a range of individual and state-level factors that we would expect to influence knowledge of the incumbent’s record, the results show that electoral competition has a strikingly positive effect on voter knowledge. Voters in states that usually had uncompetitive elections (where the average margin of victory was over 50 percentage points) are predicted to correctly identify 3.5 of their senator’s positions out of seven. Voters in states that usually had very competitive elections (where the average margin of victory was just 5 percentage points) are predicted to identify 4.5 positions correctly. Voters that live in states with high levels of competition for elected office, in other words, are more likely to know how their senators in Washington have represented them.

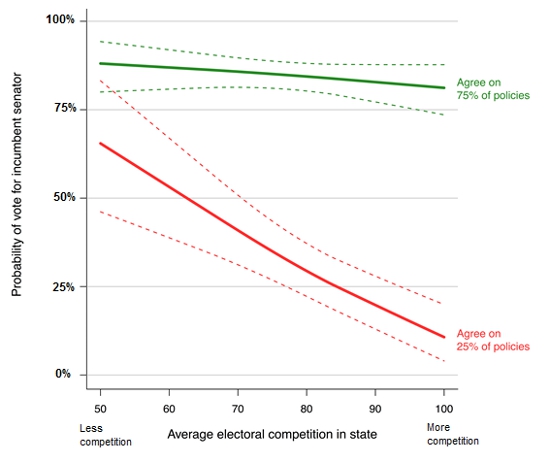

They are also more likely to hold their senators accountable for that record. I calculated the change in the probability of a constituent voting for the incumbent senator given a shift in their policy record, from agreeing with the respondent 25 percent of the time to agreeing with them 75 percent of the time. In states that usually have little competition, this shift in the incumbent’s record leads to an increased probability of voting for them to 23 percent. In states accustomed to high levels of competition, however, the same shift leads to an increase in the probability of support to 66 percent. Voters in states that tend to be competitive are more responsive to their senators’ policy record.

This conclusion is shown in one more set of simulated estimates from the data. Figure 1 shows the probability that a constituent voted for their incumbent senator, given different levels of policy agreement, across the range of electoral competition in the data. The red line is for constituents who agree with the incumbent on 25 percent of the issues; the green line for constituents who agree with the incumbent on 75 percent of the issues.

Figure 1 – Probability of vote for incumbent senator, by competition in state and level of policy agreement

Note: Solid green line represents the probability that a constituent who perceived that their policy views had been represented 75% of the time voted for the incumbent, solid red line represents the probability that a constituent who perceived that their policy views were represented 25% of the time voted for the incumbent. Dashed lines around the estimates indicate 90% confidence intervals. All individual level variables are set to their mean or mode; other state-level variables are set to the average value for all states in the analysis.

Figure 1 shows that the changing importance of policy agreement for vote choice is almost entirely due to changes in the probability that constituents who perceive low levels of agreement will nonetheless cast a ballot for the senator. Incumbents are extremely likely to win the votes of constituents whose views they have represented on 75 percent of the policies, no matter the type of state they represent. In the least electorally competitive states, these constituents are predicted to vote for the incumbent 88 percent of the time; in the most electorally competitive states this is essentially the same, at 82 percent. In contrast, the voting behavior of those who have been represented less often varies considerably, from supporting the incumbent 65 percent of the time in uncompetitive states to just 12 percent of the time in competitive states. In uncompetitive states, incumbents can count on the support of constituents whose views they have largely not represented. Only in competitive environments do these unrepresented voters desert the incumbent.

All of these results are based on long-term electoral competition in a state; I have also found that that measures of a highly competitive campaign at the time of the survey do not affect voter responses to the same degree. Rather, living in a state that routinely has competitive elections seems to change voters’ behavior, increasing their general interest in politics and the extent to which they hold incumbents accountable for their record.

The increase in the number of safe and uncompetitive districts for US legislators benefits incumbents in numerous ways. Those constituencies send clearer signals about what they want, and are easier to please as a result. Incumbents are also less likely to face serious challengers, at least in the general election. The results here reveal additional benefits: their constituents are less likely to notice policy mis-steps, and are less likely to vote against the incumbent for that reason even if they do. If voters are not aware of incumbents’ actions, or do not hold representatives accountable for them, then legislators have much greater leeway to shirk from public opinion in making policy decisions. In this regard, the decrease in electoral competition in legislative races in recent years raises numerous concerns for the functioning of our democracy.

This article is based on the paper, The Effect of Political Competition on Democratic Accountability in the September 2013 issue of Political Behavior.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1h4x7wH

_________________________________

Phil Jones – University of Delaware

Phil Jones – University of Delaware

Philip Edward Jones is an Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Relations at the University of Delaware. His research is focused on public opinion and electoral behavior, and in particular how voters respond to political elites. His work on democratic accountability has appeared in numerous journals including the American Journal of Political Science, the Journal of Politics, and Political Behavior.