Although the recent rollout of the Affordable Care Act has been plagued with problems, its earlier provisions, such as the mandate that private insurance companies offer dependent coverage until the age of 26, were implemented easily and relatively successfully. In her recent research, Kosali Simon examines the effect of this mandate and concludes that extension of parental insurance to children until the age of 26 has extended insurance to just over two million young adults. She also finds that there is little evidence that the mandate has affected labor market outcomes for young people so far.

Although the recent rollout of the Affordable Care Act has been plagued with problems, its earlier provisions, such as the mandate that private insurance companies offer dependent coverage until the age of 26, were implemented easily and relatively successfully. In her recent research, Kosali Simon examines the effect of this mandate and concludes that extension of parental insurance to children until the age of 26 has extended insurance to just over two million young adults. She also finds that there is little evidence that the mandate has affected labor market outcomes for young people so far.

In the midst of the uproar over the implementation of the major provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), there is a point worth noting. One requirement that is already in effect, seemingly effective and relatively uncontroversial is the mandate that all private insurance policies that offer dependent coverage must allow children to stay on those policies up to their 26th birthday.

When young adults in their late teens and early twenties are poorly insured or completely uninsured, their health care is often skimpy or non-existent. They may endure “job-lock” to keep paltry benefits. They suffer financial problems that can affect future credit scores. These well documented issues are why the implementation of this section of the ACA in 2010-2011 was met with little criticism from either side. Insurers didn’t complain much and the rollout was smooth, quick, and greeted with favorable media attention. But does the mandate work as intended? Offering a benefit does not mean individuals necessarily want it or find ways to take advantage of it. My recent research, undertaken with Yaa Akosa Antwi, an assistant professor of economics in the School of Liberal Arts at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, and postdoctoral fellow Asako S. Moriya of the School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University Bloomington, sought to answer this question. We used nationally representative data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau to specifically follow dependent coverage through parental employment policies.

We found that the number of young adults age 19 to 25 who are covered by their parents’ employer-provided health insurance policies increased dramatically—we estimated that just over two million young adults were added to employer-sponsored insurance policies (ESI) in the months immediately after implementation. Of that two million, 938,000 had previously been uninsured, a notable achievement. Young men were twice as likely as young women to become insured after the law took effect. Minorities were less likely than other young adults to add coverage under their parents’ plans, consistent with evidence of lower availability of employer health insurance among minority parents. Finally, we found that young adults who were single were more likely to be added to parental coverage than those who were married, even though the law applies regardless of marital status.

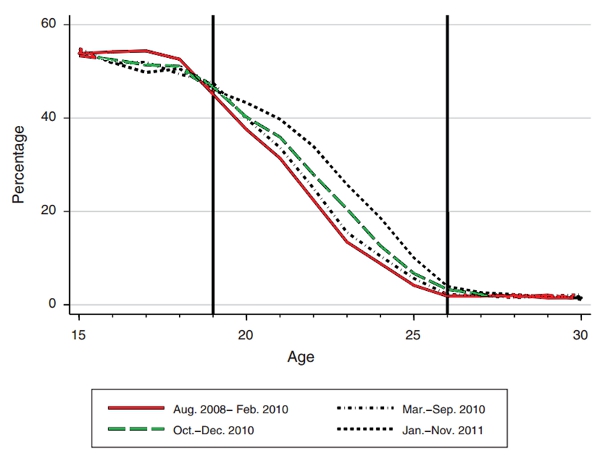

We examined not only the period when the law was implemented, from September 2010 to September 2011, but also the six months leading up to implementation after the law was enacted, and two months after implementation was completed. The period between enactment and implementation proves to be important because some health insurers said they were changing their dependent coverage rules for young adults in anticipation of the implementation of the law. This change resulted in a noticeable increase in parental coverage, as shown in Figure 1 below. We expect to see another uptick next year when a grandfather clause expires that allowed some insurers to refuse coverage to young adults whose parents have employer-sponsored insurance.

Figure 1 – Percentage of Young People Covered by Employer Sponsored Health Insurance as Parents’ Dependents

Note: Sample weighted estimates from 2008 SIPP panel, using the period from August 2008 to November 2011 as indicated by trend lines.

In addition to comparing dependent coverage for 19- to 25-year-olds before and after implementation, we examined control groups of slightly younger and slightly older children and considered changes in parent insurance rates to gauge the extent to which the increase was due to the law. This analytic approach allowed us to isolate the effect of the mandate from the recession and simultaneous decline in employer-provided policies.

With the recession as a backdrop, we also studied the impact of the mandate on the labor market, although our results are only suggestive here and due to space constraints we did not subject them to as much rigorous testing as our insurance results. We found that there is no statistically significant evidence of the mandate affecting the probability of employment of young adults, but there were small decreases in full-time employment and work hours. There was also no indication of a dramatic increase in job mobility, perhaps the result of a weak labor market that was particularly harsh for young adults at the depths of the recession. While we did not find much evidence that labor market outcomes were affected, this is certainly subject to change as the job market recovers and merits more analysis.

The same is true for all the dramatic changes in insurance coverage outcomes from the dependent-coverage provisions of the Affordable Care Act. Those include health and health care consequences as well as financial health implications of added coverage; whether coverage leads to an increase in self-employment or other changes in employment and educational pursuits among young adults; how the costs of dependent-coverage mandates are divided between employers and employees; and how take-up of this provision holds up as other health care changes are debated and implemented.

This much is clear, though: in the months following implementation of the dependent coverage requirements, the ACA erased uninsurance among targeted individuals with parental ESI by one-third. The relative lack of controversy surrounding that provision stands in stark contrast to the ACA’s other, more contentious provisions which are now the source of much frustration to policymakers.

This article is based on the paper, “Effects of Federal Policy to Insure Young Adults: Evidence from the 2010 Affordable Care Act’s Dependent-Coverage Mandate,” which appeared in the November 2013 edition of the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1ch070E

_________________________________

Kosali Simon – Indiana University Bloomington

Kosali Simon – Indiana University Bloomington

Kosali Simon is a health economist and professor at the Indiana University Bloomington School of Public and Environmental Affairs. Dr. Simon is also a research associate of the National Bureau for Economic Research. She serves on the National Advisory Committee of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Scholars in Health Policy Research Program, and on the Board of the American Society of Health Economists. She is Health co-editor of Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, and an Associate Editor of Health Economics.