Voter turnout is a perennial problem in the United States that is often amplified by a difficult registration process. Thad Hall examines two methods of simplifying and improving voter registration, the 2002 Help America Vote Act and Election Day Registration. Using census data, he argues that Election Day Registration counters many problems people typically encounter that prevent them from voting.

Voter turnout is a perennial problem in the United States that is often amplified by a difficult registration process. Thad Hall examines two methods of simplifying and improving voter registration, the 2002 Help America Vote Act and Election Day Registration. Using census data, he argues that Election Day Registration counters many problems people typically encounter that prevent them from voting.

Who is eligible to vote? This is one of the first questions that must be resolved in administering elections. Elections are about selecting who will represent us in government and we want those who are doing the choosing to be the right people. Today, we typically allow people over 18 who are citizens of a given area – the country, state, locality – to vote in the elections in their area.

The idea that people can vote in elections in their area is a simple democratic concept but under it is a larger question: how do I know who lives in which jurisdiction? We can solve this question several ways. In many countries, citizens register to vote when they notify the state as to the location of their residency. In general, as long as you notify the government when you move, you and those in your household are registered automatically at your new residence.

In the United States, voter registration is a more active process. People have to make an effort to register to vote, although it is generally combined with a government service like obtaining a driver’s license or obtaining another government service. Interest groups and political parties also work to register voters. Registering to vote requires providing proof of residence and proof of identity (typically a form of government photo identification) at either the time of registration or the first time voting.

Requiring voters to register may seem like an easy task and an easy way to have people choose to participate in the democracy; those who take this simple step show a basic interest in their government. However, as my colleague Michael Alvarez and I have written, errors in the registration process often thwart a person who thinks they are registered from actually voting.

According to the Census, 25% of people who are not registered to vote are not registered because of missing deadlines, being ill or disabled, or not knowing where to register. If registration were easier, almost 15 million more Americans would be registered to vote.

When Congress passed the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) of 2002 to address many of the problems from the 2000 election, one focus of the law was on improving voter registration. HAVA did this in two ways.

First, it required states to develop a single voter registration database for their state. A single statewide database is intended to be easier to maintain – to link with other state databases from the department of motor vehicles to death records – so that registrations can be more up to date. Also, as people make within state moves, their registrations can, theoretically, be updated easier in this type of database. Some states have more state-centered “top-down” voter registries and other states have more local-centered “bottom-up” registries. The top-down registries most resemble what was intended in HAVA.

Second, HAVA allows states who have Election Day Registration (EDR), where people register to vote in their voting precinct on Election Day, to continue to use this system. EDR states were exempted from some aspects of HAVA in recognition of the benefits that accrue from EDR.

So if HAVA recognizes the potential benefits of a centralized voter registry in improving the registration process but also acknowledges that EDR is beneficial in improving voter registration, it raises a simple question: does one reform or the other reduce problems registering and subsequently voting?

Fortunately, we can examine this question using data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey, which asks questions about registration and voting after each federal election. We can examine whether voters in EDR states have fewer problems registering to vote and encounter fewer registration problems that keep them from voting.

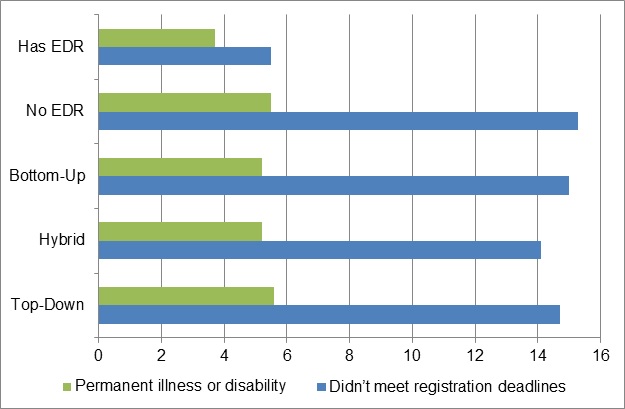

Figure 1 presents data from the 2008 CPS, aggregated across different types of state voter registration systems. We see that states with EDR have fewer people reporting not voting because of registration deadlines or because of illness or disability. EDR addresses these problems much better than any of the variations of voter registration reform that arose from HAVA.

Figure 1:

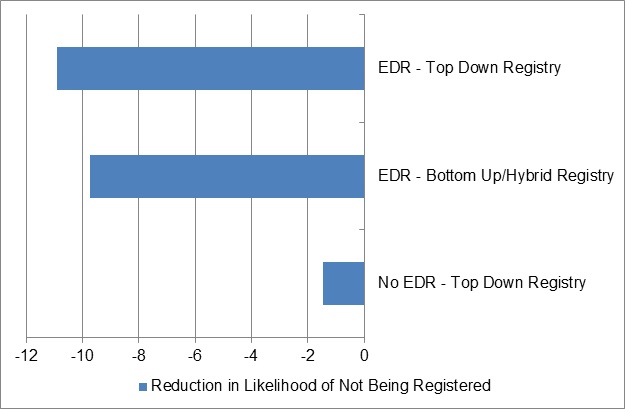

We can predict also how likely a person is not to be registered to vote based on their living in a state with EDR or living in a state with top-down voter registration. People in EDR states, regardless of the type of registration system they have, are over 9 percentage points less likely to be unregistered compared to people in a non-EDR state.

Figure 2:

Election Day registration is beneficial in any country with either high geographic mobility and/or a need to serve voters who may not be listed in a population registry correctly. EDR’s in-precinct registration efforts are helpful for governments, given the errors that often occur in data handling and entry. It also ensures that all voters who should be able to vote can vote. In a democracy, getting to vote is critical and EDR helps in cases where voters may have a problem.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: bit.ly/KxYIZu

_________________________

Thad Hall – University of Utah

Thad Hall – University of Utah

Thad Hall is an Associate Professor and the Director of the Masters of Public Administration and Public Policy Programs at the University of Utah. His most recent coauthored book, Evaluating Elections, was published in 2012. You can follow Thad on Twitter @thadhall.