Recent months have seen Republican attacks on President Obama, accusing him of presiding over an ‘imperial presidency’, but to what extent do presidents actually operate completely outside of Congress’ powers? By looking at 5,000 executive orders issued by presidents over the last 80 years Jeremy D. Bailey and Brandon Rottinghaus find that when issuing these orders, presidents tend to appeal back to Congress when the majority party is strong, and act unilaterally when the majority is weak and divided.

Recent months have seen Republican attacks on President Obama, accusing him of presiding over an ‘imperial presidency’, but to what extent do presidents actually operate completely outside of Congress’ powers? By looking at 5,000 executive orders issued by presidents over the last 80 years Jeremy D. Bailey and Brandon Rottinghaus find that when issuing these orders, presidents tend to appeal back to Congress when the majority party is strong, and act unilaterally when the majority is weak and divided.

The presidencies of Clinton, Bush and Obama have reminded us that the US president has many resources to act “unilaterally,” that is, without Congress. This is a welcome reminder of the formal powers of the American presidency, but it is also an occasion to notice when expectations do not match up with reality and to rethink the foundations of executive power.

Criticizing an “imperial” executive is an American tradition. Republican critics of Barack Obama today find ammunition in the salvos levied by Democrats against George W. Bush a decade ago. Given how frequently we talk about executive power, it is a wonder that we know so little about the decisions made by presidents to exercise unilateral power. Do presidents think they are acting unilaterally?

One problem is our assumptions. Journalistic commentary on US politics assumes that presidents turn to executive orders in order to circumvent divided government. But the reality is that empirical investigation has found very little correlation between the issuing of executive orders and divided government. That is, study after study has found that president’s “think politically” when they use unilateral powers, but divided government doesn’t seem to matter in the president’s decision to issue an executive order or not. In fact, when divided government does matter, it correlated to a decline in executive orders. This is mystery that continues to call out for scholarly study.

One explanation, offered by the University of Chicago’s William Howell, is that the strength of the majority party in Congress is what matters most, not whether that party is the same as the President’s. By his logic, presidents turn to unilateral power when Congress cannot make policy, not in order to circumvent the other party. Even if Howell is right, a related question has to do with the way presidents cast their orders, and this puzzle has much to do with the deeper question about the presumed authority for unilateral power. Do presidents justify unilateral power by appealing to prior acts from Congress?

Most unilateral power derives from powers delegated by Congress. In fact, and as we show here, early unilateral orders took the form of presidential proclamations, and 18th and 19th presidents clearly borrowed from precedents set by British kings and royal governors. More than an historical irony, the key point here is that proclamations did not create new law but instead applied existing law. Indeed, since 1792, Congress has required presidents to issue proclamations before they undertake designated activities, even if these activities derived from formal grants of constitutional authority. This pattern remains the case today as Congress requires formal legislative (statutory) justification for the establishment, alteration or implementation of thousands of laws per year.

Most unilateral power derives from powers delegated by Congress. In fact, and as we show here, early unilateral orders took the form of presidential proclamations, and 18th and 19th presidents clearly borrowed from precedents set by British kings and royal governors. More than an historical irony, the key point here is that proclamations did not create new law but instead applied existing law. Indeed, since 1792, Congress has required presidents to issue proclamations before they undertake designated activities, even if these activities derived from formal grants of constitutional authority. This pattern remains the case today as Congress requires formal legislative (statutory) justification for the establishment, alteration or implementation of thousands of laws per year.

Common sense would say that presidents would appeal to Congress. The rule of law is more palatable than the rule of men, and, at least since Justice Robert Jackson’s tripartite analysis of presidential power in the 1952 steel seizure case, presidents have sought the rhetorical mantle of congressional authority, at least in court. But it turns out that presidents do not always cite congressional authority when they issue executive orders, and it appears that presidents are strategic in their citation patterns. Presidents frequently cite specific statue, but they frequently do cite the more general and less specific “laws of the United States,” such as in George W. Bush’s 2001 executive order establishing the office of Homeland Security. Sometimes they omit mention of laws altogether, such as in Andrew Jackson’s 1832 Nullification Proclamation as well as Jimmy Carter’s 1978 executive order changing regulatory rulemaking.

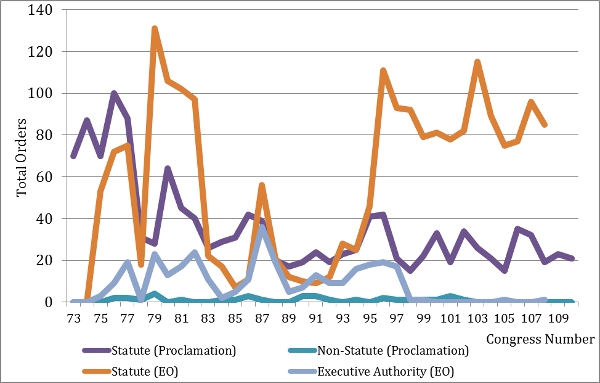

We coded roughly 5,000 executive orders and proclamations from FDR to George W. Bush. As the figure below shows, there is considerable fluctuation in citation patters, particularly in executive orders.

Figure 1 – Source of Authority by Congress

Moreover, we found that these citation patterns correlate with the expectations derived from Howell’s theory with one important exception. Presidents cite Congress when the majority party is strong and cohesive, and Presidents are more willing to rely on presidential authority alone when the majority party is weak and divided. This is true even when presidents also rely on constitutional authority, such as their authority as Commander in Chief.

But there are exceptions. Presidents are more willing to rely on their own authority when issuing orders concerning reorganization of the executive branch and when the country is at war. This suggests that presidents choose to cast their unilateral orders differently during different times. That means presidents are sometimes willing to not only act first and alone but also to resolutely characterize themselves about acting first and alone.

These findings should force us to rethink our assumptions about the nature of presidential unilateral orders. To be sure, they are only a step in approaching unilateral orders from a different vantage point, but they tell us something about the way presidents understand their own power. At a maximum, they suggest they unilateral power is not precisely unilateral and is instead shared. At a minimum these findings reveal that, in addition to being strategic about their use of power, presidents are strategic in the way they cast their power. This latter point is a necessary first step to understanding the extent to which presidents and Congress work together by way of unilateral power.

This article is based on the paper “Reexamining the Use of Executive Orders: Source of Authority and the Power to Act Alone,” American Politics Research. 42 (3): 472-502.

Featured image: President Barack Obama signs an Executive Order entitled “Establishment of the Interagency Trade Enforcement Center,” in the Oval Office, Feb. 28, 2012. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1i0mHdO

_________________________________________

Jeremy D. Bailey – University of Houston

Jeremy D. Bailey – University of Houston

Jeremy D. Bailey is Associate Professor at the University of Houston, where he holds a dual appointment in the Department of Political Science and the Honors College. He is the author of Thomas Jefferson and Executive Power (Cambridge University Press 2007), and coauthor of The Contested Removal Power, 1789-2010 (University Press of Kansas, 2013). He is co-director co-director of the Presidential Proclamations Project.

Brandon Rottinghaus – University of Houston

Brandon Rottinghaus – University of Houston

Brandon Rottinghaus is an Associate Professor and the Senator Don Henderson Scholar at the University of Houston. His research interests include the presidency, executive-legislative relations and public opinion. He is author of The Provisional Pulpit: Modern Presidential Leadership of Public Opinion (Texas A&M University Press). He is also the co-director of the Presidential Proclamations Project.