The United States is the only industrialized democracy that does not have universal health care coverage, and nearly one in five Americans do not have health insurance. The Affordable Care Act (commonly known as ‘Obamacare’) aims to extend health insurance to under and uninsured Americans by having them enroll in state or national “exchanges,” or online marketplaces; and by providing federal funds to states to expand their Medicaid coverage. Since the Act is implemented predominantly by the states, the benefits of the Act for uninsured Americans depends heavily on what states do, or refuse to do with Medicaid coverage and the state exchanges. Ling Zhu and Morgen Johansen examine what the U.S. states can do to address inequality in health insurance coverage.

The United States is the only industrialized democracy that does not have universal health care coverage, and nearly one in five Americans do not have health insurance. The Affordable Care Act (commonly known as ‘Obamacare’) aims to extend health insurance to under and uninsured Americans by having them enroll in state or national “exchanges,” or online marketplaces; and by providing federal funds to states to expand their Medicaid coverage. Since the Act is implemented predominantly by the states, the benefits of the Act for uninsured Americans depends heavily on what states do, or refuse to do with Medicaid coverage and the state exchanges. Ling Zhu and Morgen Johansen examine what the U.S. states can do to address inequality in health insurance coverage.

Health insurance aims to buffer people from very high medical costs, and in the United States uneven coverage comes from a mix of public and private sources. Older Americans enjoy nationally financed health insurance through Medicare; many employed adults are covered through employer-provided insurance; and the disabled and very poor have health insurance through Medicaid, jointly financed by the federal government and the states. However, nearly 47 million Americans are left without health insurance coverage in any given year. Low-income working aged adults and their children are most likely to slip through the cracks because they may work only part time, or are employed by businesses that cannot afford or do not offer coverage to their employees, or they simply fall into the large slices of the low-income population not covered by Medicaid programs in many states.

How Unequal Are the States?

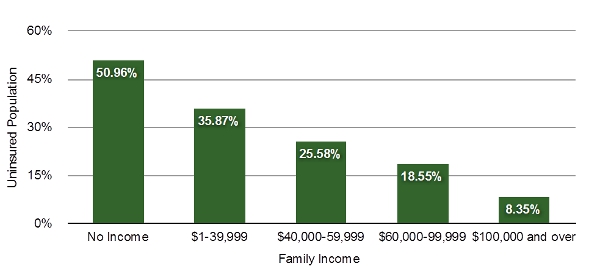

Inequality is usually discussed in terms of the percentage of the people in each state who do not have health insurance coverage from public or private sources. States with higher percentages of uninsured people are considered to have greater inequality. However, another measure of inequality is very useful: the gap between coverage for low and high-income groups. This measure of relative inequality in health insurance coverage helps to identify states in which the middle class and the poor have substantially lower rates of insurance coverage than the rich. For example, the state of Texas had a high level of overall uninsured rate of 24 percent in 2012, but is also considered quite unequal because of a large difference in coverage between higher and lower income groups.

In our recent research, we find inequality in health insurance coverage by income groups increased in nearly two thirds of the states during the past decade, with gaps most visible in states such as Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Missouri, New Mexico, and Texas – all states with large minority populations and less generous public health care provisions. Hawaii and Massachusetts, the two states that have led the way in Medicaid expansion and universal health care reforms, have seen a substantial decline in coverage inequality, even during economic downturns.

Figure 1 – Unequal Distribution of Health Insurance Coverage across Family Income Levels in Texas 2012

Source: U.S. Census Bureau 2013 Current Population Surveys.

What States Can Do to Reduce Inequalities?

The high cost of health insurance in a system where for-profit companies play a large role is the major reason why many low and moderate-income people go without coverage. Governments can try to correct the resulting inequality in several ways – by providing public funding to hospitals or clinics delivering basic services to the poor; by using regulations or payment rules to reduce the cost of insurance and health care; and by allocating public funds to extend insurance coverage. How well does each approach work?

Publicly funded or subsidized health care facilities can slightly reduce inequalities in access to care. Many public hospitals provide care to the uninsured, which is paid for by extra public funding from localities, states, and the national government. The Affordable Care Act includes expanded funding for community health clinics serving poor urban and rural areas.

Governments at all levels often pay reduced prices for Medicaid services or other publicly funded care for the poor, and they may regulate private insurance offerings to limit price increases. These approaches may enhance access and reduce inequalities up to a point, but they run into sharp partisan and interest group pushback from hospitals, doctors, and insurance companies who do not want to forego profits.

Generous eligibility criteria and public financing for public health insurance have the most substantial impact on reducing inequality, but eligibility and funding must go together or else groups that are nominally eligible for benefits will end up on waiting lists. Economic downturns can increase the need for public health insurance, while at the same time straining state budgets, prompting many states to underfund vital programs.

For decades, state governments in the United States have grappled with the reality of rising need for health insurance coverage among their low-income and disabled populations combined with limited public funding to cover the rising cost of care in systems where market actors play a big role in setting prices. Many states, especially in the South and West, have responded by sharply cutting back eligibility for Medicaid, leaving many low-income residents without insurance. The state of Texas, for example, so sharply limits Medicaid eligibility so that about 25 percent of its population is uninsured and the state is one of the most unequal in coverage.

Will Obamacare Help States Reduce Inequalities?

The funding dilemmas that states face helps to explain why the Affordable Care Act provides new federal funding to expand Medicaid to the near poor, and promises to help the states with 100 percent funding for newly eligible beneficiaries from 2014 through 2016, and 90 percent funding after that. The aim was to entice all fifty states into providing more generous and uniform Medicaid insurance to low-income Americans – greatly reducing inequality in the process. However, the Supreme Court’s review of the Affordable Care Act in June 2012 changed the rules to allow state authorities to refuse to expand coverage without losing existing Medicaid funds from the federal government.

Last week, the President’s Council of Economic Advisors released a report, which details the health and economic consequences of states’ non-actions in Medicaid expansion. So far, 24 states run by Republicans opposed to ObamaCare are refusing to expand Medicaid – leaving about 5.7 million low income Americans uninsured. Tellingly, most of these states already have high levels of inequality in coverage. Across all fifty states, millions of other uninsured people with low or modest incomes still qualify for new Affordable Care Act subsidies to help them buy private insurance on the exchanges, so the net effect will be to reduce inequalities everywhere.

According to the Council of Economic Advisors, 809,400 Americans would no longer need to borrow to pay their Medical bills if Texas expanded Medicaid coverage. By expanding Medicaid, Texas and the 23 other states can set more than 1 million people free from financial hardship, and provide thousands hundreds of Americans reliable access to clinical care and preventive care. But the refusal of many states to accept federal funds to expand Medicaid will leave inequities in place for the time being.

Featured image credit: Stephen Melkisethian Flickr, BY-NC-ND 2.0

A version of this piece also appeared as an article on the Scholars Strategy Network.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1rodYsz

_________________________________

About the authors

Ling Zhu – University of Houston

Ling Zhu – University of Houston

Ling Zhu is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Houston. Her research interests include public management, health disparities, social equity in healthcare access, as well as implementation of public health policies at the state and local level.

_

Morgen S. Johansen – University of Hawaii

Morgen S. Johansen – University of Hawaii

Morgen S. Johansen is an Associate Professor in the Public Administration Program and Public Policy Center at the University of Hawaii. Her research focuses on social equity and justice issues, particularly in health care and education.