Five years ago, Iowa became the third U.S. state to allow same-sex marriages when the state Supreme Court issued a unanimous and very unpopular decision in the case Varnum v. Brien. Since this decision, public attitudes towards same-sex marriage in the state, and the United States in general, have changed dramatically. Rebecca Kreitzer, Allison Hamilton and Caroline Tolbert draw on a unique panel telephone survey in which the same individuals are interviewed before and after the Iowa Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage to understand what groups of citizens were most likely to change their opinions on marriage rights in response to the Court’s decision. We find that the signaling of new social norms by the Court pressured some respondents to modify their attitudes. As the states continue on this rapid trajectory of legalizing same-sex marriage, we may see substantial shifts in attitudes towards LGBT rights.

Five years ago, Iowa became the third U.S. state to allow same-sex marriages when the state Supreme Court issued a unanimous and very unpopular decision in the case Varnum v. Brien. Since this decision, public attitudes towards same-sex marriage in the state, and the United States in general, have changed dramatically. Rebecca Kreitzer, Allison Hamilton and Caroline Tolbert draw on a unique panel telephone survey in which the same individuals are interviewed before and after the Iowa Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage to understand what groups of citizens were most likely to change their opinions on marriage rights in response to the Court’s decision. We find that the signaling of new social norms by the Court pressured some respondents to modify their attitudes. As the states continue on this rapid trajectory of legalizing same-sex marriage, we may see substantial shifts in attitudes towards LGBT rights.

On April 3, 2009, the Iowa Supreme Court passed down a unanimous ruling in Varnum v. Brien, which held that the state’s limitation of marriage rights to opposite-sex couples violated the state constitution’s equal protection clause, thereby establishing same-sex marriage in Iowa. This decision was particularly unpopular because only 1 in 4 Iowans thought same-sex marriage should be legal. In the Varnum decision, the Court concluded that, “We are firmly convinced the exclusion of gay and lesbian people from the institution of civil marriage does not substantially further any important governmental objective. The legislature has excluded a historically disfavored class of persons from a supremely important civil institution without a constitutionally sufficient justification. There is no material fact, genuinely in dispute, that can affect this determination.”

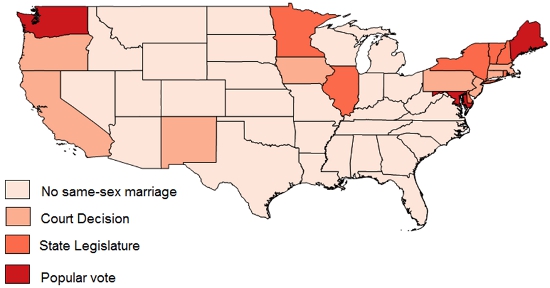

At the time of the Iowa Court decision two states had already legalized same-sex marriage through state Supreme Courts (Massachusetts and Connecticut), and since then, 16 other states have legalized same-sex marriage through courts, state legislatures and popular vote (see Figure 1 below). There are currently lawsuits pending in all states that do not currently allow same-sex marriage, and in all Circuits of the U.S. Courts of Appeal in which not all states allow same-sex couples to marry.

In the United States, state policy adoption is often a precursor to federal government policy. For example, at the turn of the 20th Century, women’s suffrage was adopted in numerous states before the federal government approved the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which granted voting rights to women. Iowa is an important early adopting state to study because of its location in the middle of the U.S., as the first state in what is now a cluster of states that allow same-sex marriage.

Figure 1 – State Institutions that Legalized Same-Sex Marriage

From previous research, we know a lot about the demographic predictors of attitudes towards same-sex marriage. For example, liberals, women, young, educated, and non-religious people are more supportive of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights. Beliefs about if homosexuality is learned, environmental or individual choice and greater exposure to gays and lesbians through friends or family also significantly liberalize attitudes towards equal rights.

We previously didn’t know how state policy affects individual public opinion on this issue. Other researchers have found evidence of a “policy feedback” effect, in which state policies regarding the environment, welfare, smoking bans or health care shape people’s opinion on those issues. Scholars argue that this feedback can happen in three ways: (1) people may become more comfortable with a policy with prolonged exposure; (2) people may change their opinion about a policy when they directly experience the policy; or (3) policies may send signals about social norms. Policies can send signals about who we are, what we stand for, and what we expect of others in the community. Our survey took place before people were exposed to the policy and before it was implemented, so the only mechanism for changing opinion that can take place in the short time period in our study is “signaling.”

We asked a random sample of Iowans about their opinion on legal same-sex marriage just days before and after the Iowa Supreme Court decision was announced. Respondents also answered a question in the second wave of the survey regarding if they thought a constitutional amendment should be passed to overturn the controversial ruling of the Court. Because we asked the same people the same question just days apart, we can learn about who changed their opinion in response to signals sent from the Court.

We find that the new policy sent a strong signal that the state’s previous law banning same-sex marriages was discriminatory. Certain groups—Democrats, educated, young, non-religious, non-Evangelical, and people that know gay/lesbian family or friends—were the most receptive to the signaling of a new norm from the Court’s decision. These groups were most likely to change their opinion from opposing to favor same-sex marriage. For example, respondents between the ages of 18-25 increased their support by 4.4 percent and non-evangelicals increased their support 3.4 percent. Having LGBT friends or family increased support by 6.5 percent, all other factors held constant. These changes in opinion are substantively large considering the short time period between the telephone surveys.

Why did these people change their opinion? It may be that these groups faced increased social pressure to conform to the newly imposed norm of same-sex marriage. Alternatively, the ruling may have simply pushed respondents on the edge of accepting same-sex marriage to do so.

We also find that support for same-sex marriage prior to the Court’s decision strongly predicts whether the respondent believes the decision should be accepted or a constitutional amendment should be passed. Yet respondents who are highly educated, non-evangelical, or with gay or lesbian friends and family are far more likely to support the Court’s decision, even when they personally disagree with the Court’s ruling.

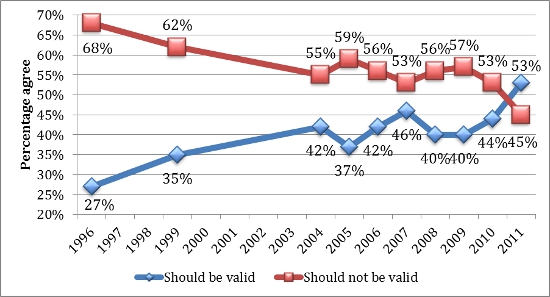

Since the Court’s decision in 2009, support for same-sex marriage in Iowa has continued to increase. In our most recent poll, conducted in November 2013, support for same-sex marriage had increased to nearly 50 percent. After the Court decision, support for civil unions has remained lower than support for same-sex marriage. This mirrors national trends, which show that support for same-sex has surpassed opposition.

Figure 2 – Support for same-sex marriage 1996 – 2011

Note: Trends shown for polls in which same-sex marriage question followed questions on gay/lesbian rights and relations. Gallup survey question: Do you think marriages between same-sex couples should or should not be recognized by the law as valid, with the same rights as traditional marriages?

As states continue to legalize same-sex marriage through state supreme courts and federal circuit courts, signals are sent to the residents of other states and the nation as a whole. On July 28th, the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals struck down Virginia’s ban on same-sex marriage (though the decision will not go into effect until at least August 18th). This case is the 29th consecutive ruling from a federal or state court since the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the federal Defense Against Marriage Act (DOMA) last summer. These repeated signals from the courts foretell shifting attitudes among the people. And as more people support LGBT rights, politicians respond to their constituents with even more liberal policy.

This article is based on the paper ‘Does Policy Adoption Change Opinions on Minority Rights? The Effects of Legalizing Same-Sex Marriage’, in Political Research Quarterly.

Featured image credit: Rich Renomeron CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1uCQ9BY

______________________

Rebecca Kreitzer – University of Iowa

Rebecca Kreitzer – University of Iowa

Rebecca Kreitzer is a fifth year Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Iowa studying American politics. Specifically, she is interested in gender and sexuality politics. Her research deals primarily with state policy adoption, diffusion, implementation and feedback.

_

Allison Hamilton – University of Tennessee

Allison Hamilton – University of Tennessee

Allison Hamilton has her PhD from the University of Iowa, and is currently at the University of Tennessee. Her research interests include political participation, voting behavior, campaigns, institutional rules and policies, and women in politics.

_

Caroline Tolbert – University of Iowa

Caroline Tolbert – University of Iowa

Caroline Tolbert is Professor of Political Science at the University of Iowa. Her research explores voting, elections, public opinion and representation widely defined. She has contributed to many subfields including digital politics and information technology policy, voting and elections, public opinion, American state politics, direct democracy and race and politics.

1 Comments