Tax reform does not lack for supporters on both sides of the aisle in Congress, but despite this, it continues to be a difficult proposition. While many believe that tax breaks are especially durable, in new research, Jake Haselswerdt finds that, this is not borne out by the evidence. In fact, a tax break is more than four times more likely to be eliminated than a non-tax program. He argues that while individual tax breaks, particularly those that benefit businesses and the wealthy, are relatively short lived, more comprehensive reform to eliminate a number of tax breaks may be much harder, especially if it takes on the more durable tax breaks that benefit the middle class.

Tax reform does not lack for supporters on both sides of the aisle in Congress, but despite this, it continues to be a difficult proposition. While many believe that tax breaks are especially durable, in new research, Jake Haselswerdt finds that, this is not borne out by the evidence. In fact, a tax break is more than four times more likely to be eliminated than a non-tax program. He argues that while individual tax breaks, particularly those that benefit businesses and the wealthy, are relatively short lived, more comprehensive reform to eliminate a number of tax breaks may be much harder, especially if it takes on the more durable tax breaks that benefit the middle class.

Few ideas have a more impressive and influential array of supporters in Washington than tax reform. Current Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden (D-OR) and House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI) are both champions of tax reform. So was Wyden’s predecessor, Max Baucus (now the Ambassador to China) and Camp’s likely successor when term limits will force him to give up the gavel next year, current Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R-WI). For good measure, add President Barack Obama and his 2012 opponent, Mitt Romney to the list. Of course, observers of tax politics know that this nominal support for the concept of “tax reform” counts for little in terms of the chances for an actual tax code overhaul. Recently released tax reform drafts from both Baucus and Camp have landed with a thud on Capitol Hill and K Street. As tax historian Joseph Thorndike has said, “The smart money bets against tax reform — always and everywhere.” Comprehensive reform, which involves ending or restricting a host of tax breaks (or “tax expenditures”) to either lower rates, reduce the deficit, or both, is a difficult political proposition.

Why is this, exactly? Is it a simple matter of the well-known status quo bias of American politics, which makes any sort of large-scale policy change difficult? Or is there something about tax breaks in particular that makes them more politically durable than other policies? Some observers certainly think there is. Tax policy expert Edward Kleinbard complains that tax breaks, once enacted, “simply disappear below the surface into the mainstream of baseline revenues.” Economists Justin Wolfers and Betsey Stevenson argue that these provisions have “immense staying power. Because they aren’t as visible as outright spending, they aren’t subject to the scrutiny of campaigns to pare back waste or assess effectiveness.”

The notion that tax breaks are especially durable is widely held, and Congress’ tendency to renew most expiring provisions in so-called “tax extender” legislation tends to reinforce it. But it’s actually a misconception. Using a newly expanded dataset of all new spending programs and all tax expenditures that were created between 1974 and 2003, I find that tax breaks did not last longer than other types of policies. In fact, they were systematically more likely to be eliminated, especially over long periods of time.

Before I go further, a word about the data. I start with a longitudinal database (originally assembled by Christopher Berry, Barry Burden and William Howell) of all programs in the Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance, the federal government’s nearly exhaustive list of programs available to just about any entity you can think of. I say “nearly,” because there’s one very important type of program missing: tax expenditures. For those, I rely on a 2005 Government Accountability Office report that includes a list of all tax expenditures reported by the Treasury Department between 1974 and 2004, including the years that these provisions were in effect. By merging these data sets, I can compare the durability of 132 tax breaks with 1,953 other programs, over a total of 18,835 “program-year” observations.

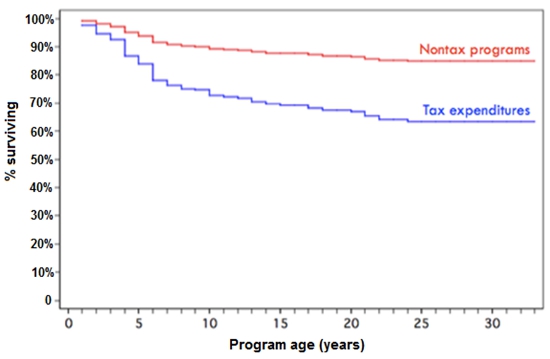

Figure 1 below shows the results of this comparison, in the form of survival curves for tax and nontax policies. As the curves indicate, tax breaks are at a higher risk of elimination than nontax policies, particularly over the long term. In fact, after ten years, my model predicts that a tax break is 4.3 times more likely to be eliminated than a nontax program, all else equal (note that this estimate is calculated from a different model than the simple one used to generate the figure). This pattern holds when controlling for a host of contextual political and economic factors. And no, this is not just a 1986 effect – even setting aside the numerous provisions eliminated in the 1986 Tax Reform Act, tax breaks were significantly more likely to be eliminated than other kinds of policies.

Figure 1 – Survival curves for tax and nontax policies

So why is this the case? It may have something to do with the dominance of the powerful Senate Finance and House Ways and Means Committees, which may be less susceptible to interest group capture than committees with a narrower purview (think Agriculture). It might also have something to do with the lack of bureaucratic advocacy for tax breaks. Federal employees are an underrated source of support for the programs that employ them (remember, one of the corners of the “iron triangle” is the bureaucracy), but tax expenditures enjoy little bureaucratic support. Quite to the contrary, bureaucrats at the Treasury Department and the IRS are frequently hostile to tax breaks, since they reduce revenue and complicate the tax agency’s job.

Does this mean that tax reform is actually easy? Of course not. Just because tax breaks don’t last as long as other kinds of programs doesn’t mean they are “easy” to eliminate in any absolute sense. And eliminating a large number of them in a comprehensive package, which has the potential to draw opposition from innumerable entrenched interests, may be exponentially harder.

Moreover, a deeper dive into the data on exactly which tax breaks tend to be eliminated most often highlights some other challenges. Despite what you’ve heard about wealthy special interests, tax breaks that benefit businesses and the wealthy have been the shortest lived. Corporate tax breaks have been more vulnerable than individual tax breaks. Deductions (most of which primarily benefit high-income itemizers) have been more vulnerable than credits and exclusions. And provisions intended to advance social welfare (i.e., directly benefit members of the public) are longer-lived than those for other purposes. Over the years (particularly 1986), these patterns have produced a tax code which is relatively light on the sorts of “special interest” loopholes that vague champions of tax reform want you to believe will finance a major reform effort. Certainly, such provisions exist, but eliminating them won’t get you very far in terms of revenue. As other researchers have noted, most of the big-ticket tax expenditures in the code benefit a lot of people, including large portions of the middle class, even as they also provide windfalls for the more well-to-do.

These findings suggest that would-be reformers should both take heart and not kid themselves. Tax breaks are definitely mortal, but attacking the more popular and broad-based provisions is an uphill battle. In the near term, it may be more fruitful to focus on specific reform goals, such as modernizing the taxation of US-based multinational corporations, that don’t necessarily require lots of new revenue.

This article is based on the paper, ‘The Lifespan of a Tax Break: Comparing the Durability of Tax Expenditures and Spending Programs’ in American Politics Research.

Featured image credit: 401(K) 2012, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1tBB3v6

______________________

Jake Haselswerdt – University of Missouri

Jake Haselswerdt – University of Missouri

Jake Haselswerdt is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and the Truman School of Public Affairs at the University of Missouri, currently on leave as a Robert Wood Johnson Scholar in Health Policy Research at the University of Michigan. His research focuses on the politics of tax and social policy, including the interaction of policy with public opinion and political institutions.