In recent years the United Nation’s Agenda 21 policy has become the rallying cry for many in the Tea Party who believe that the U.N. threatens American sovereignty. This concern led the introduction of anti-Agenda 21 legislation in 26 states in 2012 and 2013. Karen Trapenberg Frick, David Weinzimmer and Paul Waddell find that conservative states were more likely to see the introduction of anti-Agenda 21 legislation. They writes that the widespread outbreak of introducing legislation may indicate a longer-term situation whereby sustainability opposition becomes part of the state agenda with continued public discussion and media attention. In light of this, planning communities must consider new methods of public engagement that encourages genuine dialogue.

In recent years the United Nation’s Agenda 21 policy has become the rallying cry for many in the Tea Party who believe that the U.N. threatens American sovereignty. This concern led the introduction of anti-Agenda 21 legislation in 26 states in 2012 and 2013. Karen Trapenberg Frick, David Weinzimmer and Paul Waddell find that conservative states were more likely to see the introduction of anti-Agenda 21 legislation. They writes that the widespread outbreak of introducing legislation may indicate a longer-term situation whereby sustainability opposition becomes part of the state agenda with continued public discussion and media attention. In light of this, planning communities must consider new methods of public engagement that encourages genuine dialogue.

Be it resolved by the House of Representatives of the State of Kansas: That we recognize the destructive and insidious nature of United Nations Agenda 21 and hereby expose to public policy makers the dangerous intent of the plan… State of Kansas Approved House Resolution, 2012

For more than 20 years, the United Nations’ (U.N.) Agenda 21 Rio Declaration on Development and Environment, a source document on sustainable development intended to help governments understand and undertake measures to cope with climate change, was little known to U.S. city planners. Recently, however, it has become a rallying cry for Tea Party, property rights advocates and others, who have succeeded in introducing anti-Agenda 21 legislation in half the country’s state legislatures.

The Kansas resolution, like similar resolutions proposed in many other states, describes the non-binding action plan that grew out of the 1992 U.N. Conference on Environment and Development in this way:

…The United Nations Agenda 21 is a comprehensive plan of environmental extremism, social engineering and global political control… This United Nations Agenda 21 plan of radical so-called “sustainable development” views the American way of life of private property ownership, single family homes, private car ownership, individual travel choices and privately owned farms as destructive to the Environment…

Concerns about American sovereignty are not new, nor are assertions of a U.N.-led “one-world government” domination, which undergird this narrative of a U.N. of restricting individual property rights and redistributing wealth from developed to developing nations in the name of questionable climate change. What is new is the degree of legislative activism targeting sustainability planning efforts at all levels of government, from activists attending meetings in force to oppose local plans, to state legislation introduced to stop perceived Agenda-21-oriented practices by states and local governments.

In recent research, we sought to understand this trend by examining the proposals and passage of state bills, which were introduced in over half the state legislatures in the U.S. These proposed bills take the form of binding legislation or non-binding resolutions, and use language similar to the above Kansas resolution as well as that contained within the U.S. Republican Party’s 2012 platform. This language is also found in the first bill to be passed by both chambers unanimously in 2012 in the State of Alabama.

The loose coalition of activists consists of several thousand individuals throughout the U.S. call themselves “Americans Against Agenda 21,” or “AgEnders,” and there are numerous others actively engaged but not officially members of this group. Activists affiliate with local Tea Party, property rights, and liberty groups. The John Birch Society and American Policy Center promote anti-Agenda 21 opposition and legislation, and former Fox News host Glenn Beck added his name to a dystopian futuristic novel with an afterward that instructs citizens on recognizing and stopping Agenda 21. Proponents of this movement widely circulate training materials, YouTube videos, and tool kits for purchase. Agenda 21 opponents counsel cities to “get out of ICLEI” by cancelling their memberships to ICLEI-Local Governments for Sustainability (International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives), a non-profit organization which assists cities with climate action planning. Some websites claim that upwards of 135 U.S. cities have done so.

Interviews with activists suggest that the counter-movement transcends political lines, citing the Northern California-based group, Democrats Against Agenda 21 and affiliated Post-Sustainability Institute, which argue that public planning processes purposely block genuine citizen input; that unelected, regional bodies are unconstitutional; and, that redevelopment and sustainability planning infringe upon on property rights.

In order to understand Agenda 21’s rapid ascendance on state legislative agendas nationwide, we compared all 50 states by first constructing a national database of state level data gathered from a variety of publicly available sources, typically reflecting the situation in 2010, as this was a watershed moment in which the Tea Party and other conservative candidates won legislative seats. We then tested expectations about what state-level characteristics make some state legislatures more likely than others to introduce anti-Agenda 21 legislation. We also focused on the state of Arizona as a representative case, as its population’s sociodemographic characteristics and key actors’ narratives and modes of participation parallel findings from research on Tea Party and property rights activism and our quantitative analysis. We interviewed 21 leading participants and observers of anti-Agenda 21 mobilization in Arizona and the U.S with high levels of legislative activity.

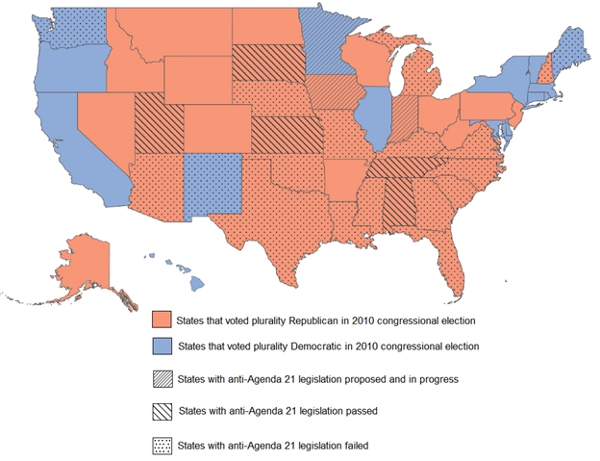

From 2012 to early 2013, legislators in at least 26 states introduced anti-Agenda 21 legislation (see Figure 1 and linked Table). All bills opposed or restricted Agenda 21 sustainability practices and object to any relationships with the United Nations and non-governmental organizations including ICLEI. During the period of our research, Alabama was the only state to enact binding legislation. Four states passed resolutions (Kansas, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Utah). During this same period, another four bills were active and 31 failed. About one-third of the failed bills that were to be heard in both houses passed out of the house of origin — often with high votes in support and along party lines with Republican members in favor.

Figure 1 – Status of State Legislation in relation to the percentage of votes for Republican Candidates for U.S Congress House seats in the 2010 federal elections

Notes: (1) For states with multiple pieces of legislation, the legislation that advanced the furthest is shown (i.e., if one bill passed and a subsequent bill failed, the state is indicated as a state with anti-Agenda 21 legislation passed)

(2) Of the states that passed legislation, Alabama and Missouri passed binding bills, while the others were resolutions. Missouri’s bill ultimately failed, however, after a veto by the governor.

(3) Tennessee’s legislature passed a resolution that did not receive the governor’s signature. Resolutions do not require a governor’s signature, however, so the resolution is considered to have passed.

Although the sustainability proponents we interviewed interpreted as a success the failure of bills to become law, they acknowledged that the issue will likely resurface either through legislation or in other ways, such as activists turning their attention to local planning issues or seeking to unseat elected officials who support sustainability. In fact, the Tea Party and property rights activists we interviewed view bills that have moved out of only one chamber not as failure, but promise for the future. Although non-binding resolutions do not have the force of law, activists consider passed resolutions as the foundation for subsequent binding legislation and as motivation to colleagues for replication nationwide. They hope the resolutions will cause a chilling effect whereby states, regional agencies, and cities would be reticent to implement Agenda 21-like practices for fear of provoking future negative public debates and interactions.

In our exploratory quantitative analysis, we found that conservative states–those with higher shares of owner-occupied households, military jobs, greater income inequality, higher levels of public expenditures on social services, higher Republican voting fraction, and fewer zero-car households—were more likely overall to see the introduction of anti-Agenda 21 legislation.

We then examined the themes of opposition voiced by Arizona’s activists, which mimic themes previously identified in Tea Party-related literature — from citizen patriots battling big government to activists facing threats from above and below as well as the need to protect the U.S. Constitution and founding principles of the country. Opposition to the United Nations factored heavily as well in public discussions and all state bills introduced. So too was questioning the role of government and planning, which was prominent in the language of the bills. As a result, the narratives facilitated a contentious “us versus them” environment with much identification and deliberation about the “other.” Interviewees on both sides often referenced the oppositions’ loose facts and fear mongering.

Organized and passionate opposition is part and parcel of planning. Citizen concerns related to property rights, smaller government, government distrust and skepticism, and reduced taxes have festered for decades. However, there are two new elements, particularly in the eyes of the participants and national observers. First, planning opposition has been at unparalleled levels; it is unusual for organized opposition to rise above an individual local or state level and to become as widespread as occurred through these numerous state bills.

Much opposition reflected in the bill language and our interviews relates to activists’ perceptions that they have been deceived by “rigged” planning processes that have predetermined outcomes geared towards sustainability practices, subversive guiding principles of sustainability, and purposeful imposition and mobility of these plans from city to city. One conservative interviewee argued, “The towns may be different, but the plans are not.”

We believe this widespread outbreak of introducing legislation may indicate a longer-term situation whereby sustainability opposition becomes part of the state agenda with continued public discussion and media attention. The bills — even if they fail — inspire imitation and create momentum and learning opportunities, as evidenced by the bills’ proliferation across the U.S. This was confirmed by our interviewees and an analysis of documents and online materials. Adopted resolutions may invoke a chilling effect, dampening future activities such as curtailing city-based ICLEI memberships or sustainability planning.

Second, social media and other internet communications facilitated the spread of activist positions and proposed legislation, and enabled digitally networked activism to flourish nationally. Participants quickly and widely spread information, articulated counter-narratives, and send out rallying cries to generate greater participation and awareness. As many remarked, public agencies no longer control messaging through their websites and sympathetic mainstream channels; instead planning activities are becoming more visible through the lenses of critical activists.

Thus, planning and research communities would be well-advised to understand this and not dismiss it as unworthy of careful deliberation. A practitioner supportive of sustainability reflected that some good might result from recent legislative uprisings:

(I)f it makes planners realize that they have to get true community engagement… The criticism is that planners push through something. They really have to walk it like they talk. People don’t want to show up at planning meetings. Maybe this whole issue has accelerated how we can do community engagement well and share best practices. It’s maybe about having more planners listen and be respectful to a diversity of opinions.

The above statement calls attention to limitations of public outreach and input processes for plan development, which are well covered in planning research. Those interviewed on both sides recounted with frustration that the opposition was dismissive, dogmatic, and unwilling to engage in genuine dialogue. A way forward may be continued research and practice drawing from the political theory of agonism to reframe civic engagement. In agonistic contexts, actors come to consider their opposition as legitimate adversaries rather than as enemies unworthy of engagement. In such moments, actors retain their core values and identities and may find common ground with others in a limited way or agree to disagree. Group consensus is not a goal, but compromise through bargaining and negotiations may occur.

While challenging, the long-term objective is to transition when feasible, from highly antagonistic, counterproductive encounters to interactions of agonistic debate. Thus, our findings underscore the need for on-going research and attention to agonism’s potential for planning and sustainability debates. We must also consider the difficulties and opportunities that come with an evolving hybrid media system of communication.

This article is based on the paper, ‘The politics of sustainable development opposition: State legislative efforts to stop the United Nation’s Agenda 21 in the United States’ in Urban Studies.

Featured image credit: Susan E Adams (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/V7hjQV

______________________

Karen Trapenberg Frick – University of California, Berkeley

Karen Trapenberg Frick – University of California, Berkeley

Dr. Karen Trapenberg Frick is Assistant Adjunct Professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning at UC Berkeley. She is Co-Director of the UC Transportation Center and Assistant Director of the UC Transportation Center on Economic Competitiveness in Transportation (UCCONNECT). Her research focuses on the politics and planning of transport infrastructure. Her related research which won a “Paper of the Year” award on Tea Party and property rights activists’ perspectives on planning and planners’ responses may be found at the Journal of the American Planning Association.

David Weinzimmer – University of California, Berkeley

David Weinzimmer – University of California, Berkeley

David Weinzimmer is a graduate student in the joint degree program in city planning and transportation engineering at the University of California, Berkeley. His past research has included performance metrics in transit, bicycle and pedestrian safety, and the impact of corporate shuttles on residential location choice.

Paul Waddell – University of California, Berkeley

Paul Waddell – University of California, Berkeley

Paul Waddell is Professor of City and Regional Planning and Department Chair at the University of California, Berkeley. He teaches and conducts research on modeling and planning in the domains of land use, housing, economic geography, transportation, and the environment. He has led the development of the UrbanSim model of urban development and the Open Platform for Urban Simulation, now used by Metropolitan Planning Organizations and other local and regional agencies for operational planning purposes in a variety of U.S. metropolitan areas such as Detroit, Houston, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, San Francisco, and Seattle, as well as internationally in a growing list of cities in Europe, Asia, and Africa. His current research focuses on the assessment of the impacts of land use regulations and transportation investments on outcomes such as spatial patterns of real estate development and prices, travel behavior, emissions, and resource consumption. He is also working on ways to engage public participation in making complex policy choices.

1 Comments