Government failure and inaction has become an increasingly common aspect of the U.S. political system, whether it is due to political polarization as in the government’s shutdown in 2013, or through poor planning, which characterized the rollout of the Obamacare website. But how do voters apportion blame for these sorts of failures? In new research, that tests how people react to expert testimony that apportions blame to a particular political party, Jeffrey Lyons and William P. Jaeger find that even when experts say otherwise, people still blame the party that rivals their own political views for the failure. They write that their findings go against the idea that a better informed electorate would be less partisan – in actuality, people simply ignore the extra information they are given if it challenges their beliefs.

Government failure and inaction has become an increasingly common aspect of the U.S. political system, whether it is due to political polarization as in the government’s shutdown in 2013, or through poor planning, which characterized the rollout of the Obamacare website. But how do voters apportion blame for these sorts of failures? In new research, that tests how people react to expert testimony that apportions blame to a particular political party, Jeffrey Lyons and William P. Jaeger find that even when experts say otherwise, people still blame the party that rivals their own political views for the failure. They write that their findings go against the idea that a better informed electorate would be less partisan – in actuality, people simply ignore the extra information they are given if it challenges their beliefs.

Government failures are a reality in any political system, and have received a lot of attention in the United States in recent years. In the past decade, failures have included the government’s woeful response to Hurricane Katrina, and in more recent years Congressional gridlock has produced government shutdowns and the inability to make policy and tackle societal problems. The question is, who do people blame when these failures occur?

We conducted an experiment to find out. People were given a fake newspaper article about a state government’s failure to balance the budget which resulted in a credit downgrade (similar to the recent problems we have seen with the federal government). We made slight changes to the article that different groups of people read to see how the changes influenced who they blamed for the failure. We changed who was in control of the governor’s office and legislature, as well as what kind of information people were given about who was responsible. Some people read an article where a spokesperson for a credit-rating agency (a non-partisan source) blamed the other party, while others read an article where the spokesperson blamed their own party. The goal of this was to see how people would change their blame when given non-partisan, expert testimony.

We found that people overwhelmingly blame the other party for the failure. Democrats blamed Republicans, and Republicans blamed Democrats. This is not entirely surprising and is consistent with what other scholars have found. What was most interesting was how people used the expert, non-partisan testimony. Rather than listening to the expert and considering what they had to say, the participants were very selective about how they used the information. When the expert told them that the other party was to blame, we find that people used the information and placed even more blame on them than they would have if they did not have any expert testimony. But, when the expert blames their own party, the information is ignored and people just continue to blame the other party for the failure.

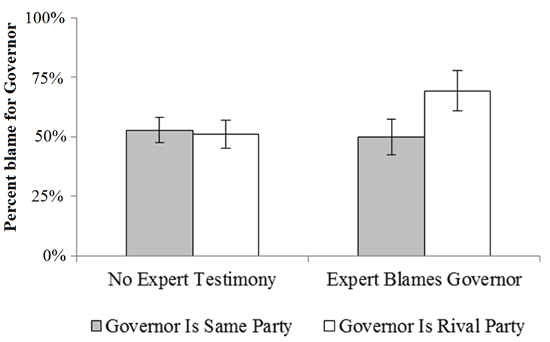

Figure 1 – Blame for Governor, by Governor’s party and expert testimony

The figure shown above illustrates this pattern. The two bars on the left represent how much blame was given to the governor on average when there was no expert testimony. The grey bar is when the governor is of your own party, and the white bar shows how much blame was placed on the governor when the governor is of the opposing party. The vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals. We see that there is virtually no difference between these two bars, meaning that there was little difference in how much blame was given when there was no information present.

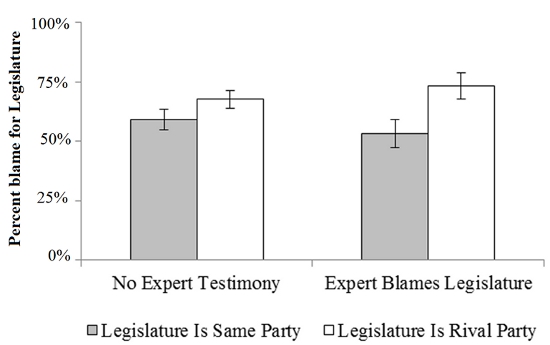

However, turning to the two bars on the right, we see that the story is quite different. These two bars represent cases where the expert blames the governor. Here we see that the white bar is much higher than the grey bar, because the governor is of the rival party. Put simply, when the expert blames the other party, people listen and use that information. But when the expert blames their own party, people tune it out, seemingly unwilling to listen and blame their own party. The same general pattern emerges in the figure shown below where we are looking at levels of blame given to the legislature instead of the governor.

Figure 2 – Blame for Legislature, by Legislature’s party and expert testimony

Some qualifications that need to be mentioned about the study is that we are only looking at one kind of information being supplied – expert, non-partisan testimony about who is to blame. It is possible that other kinds of information could have different effects and actually reduce partisan blame as some have found. The other qualification worthy of mention is that the hypothetical scenario presented pertained to state politics. It is possible that information is used differently in the context of state matters where general levels of knowledge are low, and information is taken as a more credible signal in national politics.

What does this tell us? For one, representative democracy requires that the people are able to hold elected officials accountable for performance in office. When politicians fail to produce desired outcomes, citizens need to be able to accurately place blame and potentially vote them out of office. We have shown that rather than consider relevant facts, people are more interested in pointing the finger at the other party.

Further, many see information as being a potential savior of the electorate – arguing that if people had access to more unbiased information, they would be less partisan and more willing to compromise or see other perspectives. The results from this experiment suggest otherwise. Information is largely used as a weapon by partisans. When the information confirms their beliefs, they use it, and when it challenges them, they ignore it. Partisanship colors much of the American political experience, and expecting people to take off the partisan glasses when considering information about who is to blame does not appear to happen.

Featured image credit: J E Theriot (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

This article is based on the paper ‘Who Do Voters Blame for Policy Failure? Information and the Partisan Assignment of Blame’ in State Politics and Policy Quarterly.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1qk5QGy

_________________________________

Jeffrey Lyons – University of Denver

Jeffrey Lyons – University of Denver

Jeffrey Lyons is a Lecturer of American Politics at the University of Denver where he researches and teaches classes on American political behavior and state and local politics. His research can be found in American Politics Research, State Politics and Policy Quarterly, and Political Communication.

_

William Jaeger – University of Colorado at Boulder

William Jaeger – University of Colorado at Boulder

William Jaeger is a doctoral candidate at the University of Colorado at Boulder and has been published in State Politics and Policy Quarterly.