State legislatures vary considerably in their organization, especially in the scope of leadership powers and the degree of autonomy given to legislative committees. Since the members themselves often have power over how their own legislative bodies are organized, political scientists have a keen interest in understanding why members choose to give committees greater autonomy in decision-making. Tanya Bagashka and Jennifer Hayes Clark argue the decision to grant more autonomy to committees is influenced by the type of electoral system (open versus closed primaries) from which legislators are elected.

State legislatures vary considerably in their organization, especially in the scope of leadership powers and the degree of autonomy given to legislative committees. Since the members themselves often have power over how their own legislative bodies are organized, political scientists have a keen interest in understanding why members choose to give committees greater autonomy in decision-making. Tanya Bagashka and Jennifer Hayes Clark argue the decision to grant more autonomy to committees is influenced by the type of electoral system (open versus closed primaries) from which legislators are elected.

The importance of reelection to legislators is no mystery. For a legislator to follow through on campaign promises and ultimately pass policies, it is necessary that she remains in office to see proposals through to fruition. Since legislators have control over the internal rules of the legislature, they may alter rules in order to facilitate reelection. For instance, members from agricultural districts seek positions on the Agriculture Committee where they can have great influence over agricultural policies and where they may also have the ability to can provide farm subsidies or other benefits to their district. This allows the member to claim credit to her constituents to help secure reelection.

How much influence legislators have over policy and “bringing home the bacon” is related to committee system autonomy, which refers to the extent to which committees are able to receive, screen, shape and affect the passage of legislation. If committees are truly autonomous, the rules would stipulate that all legislation has to be referred to a committee for consideration before final passage. Committee autonomy is greater when bills referred to the committees do not have to be considered and/or reported back to the floor, when there are no deadlines for committee action, and when it is more difficult to remove bills from the committees before the committee has had a chance to act. Consequently, legislators have greater control over policy and pork when committees are more autonomous. Committee members have great discretion in crafting bills, and once bills reach a floor vote, non-committee members act in deference to the committee members.

In our current research, we argue that the level of autonomy legislators grant committees is directly related to the inclusiveness of the selectorate, or the body of voters electing the legislator. The inclusiveness of the selectorate is dependent upon the types of primaries employed by state parties. In the United States, the primary system is the method by which most legislative candidates receive their party’s nomination, which allows them to contest the general election under their party’s label. State primaries vary in many ways, and one of these important differences concerns who can participate in the state party’s primary. A number of state parties (e.g., Connecticut, Florida, New York, and Pennsylvania currently) use a closed primary system in which voters must declare membership of a particular party by a specific date prior to the election in order to vote in the primary. Other states (e.g., Michigan, Missouri, Minnesota, and Wisconsin currently) use open primaries which allows voters to choose which party’s primary they opt to vote without a requirement of declaring membership to the party. Others employ some variation or hybrid of the closed or open primary system (known as semi-open or semi-closed primaries).

Open primaries are the most inclusive and encourage participation from cross-over voters and Independents since the barriers of participating in the party’s primary is fairly low. Closed primaries are the most exclusive and discourage cross-over voting. More inclusive primary systems motivate candidates to appeal directly to the voters, circumventing party leaders. Additionally, more inclusive primary systems require that candidates reach out to a broader group of voters, many of whom may not be members of the candidates’ party. On the flip side, in exclusive systems (i.e., closed primaries), candidates are more beholden to party elites who maintain considerable control over the process.

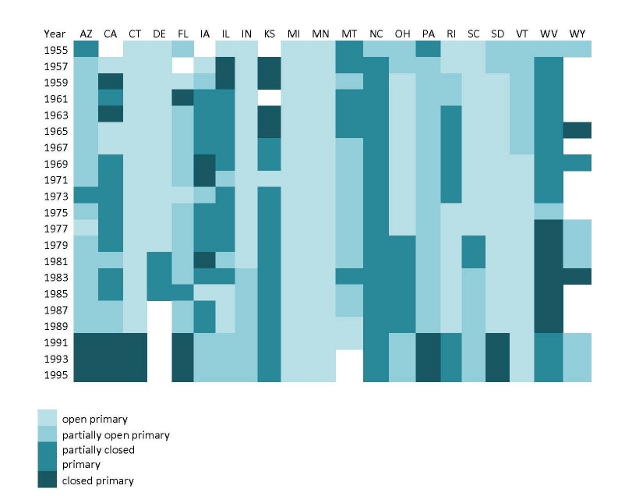

To address our question, we first gathered data on the methods of candidate selection in 24 states between 1955 and 1995, shown in Figure 1. We then combined these data with committee autonomy scores created by Nancy Martorano for the same states and time frame. Our analysis demonstrates that the inclusiveness of the selectorate, or the body electing the candidates, does have a significant effect on committee autonomy. When candidates were elected through more inclusive primary systems (i.e., open primaries), they subsequently altered rules to make committee systems more autonomous.

Figure 1: Primary System Type, 1955-95

We also investigated the effect of term limitations on committee system autonomy. Since our argument assumes that legislators do seek reelection, it is important to consider whether statutory or constitutional restrictions on legislative service affect committee autonomy. From 1955 to 1995, only six states (Arizona, California, Florida, Michigan, Ohio and South Dakota) had enacted term limits. Our results revealed that term limits were not a significant predictor of committee autonomy.

This research suggests that electoral considerations have broad effects on politics, not simply confined to campaigns, but can also influence the very design of political institutions. It has long been recognized that institutional design has a profound influence over policy outcomes. Therefore, changes in electoral rules should be evaluated not only on the basis of their potential influence over who can participate but also on their eventual consequences for the design of our legislative institutions.

This article is based on the paper ‘Electoral Incentives and Legislative Organization’ in State Politics & Policy Quarterly.

Featured image: Maryland House Judiciary Committee Credit: Maryland GovPics (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/VQGWG5

_________________________________

Tanya Bagashka – University of Houston

Tanya Bagashka – University of Houston

Tanya Bagashka is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Houston. Her primary areas of research interest include comparative institutions, corruption, and post-communist politics.

_

Jennifer Hayes Clark – University of Houston

Jennifer Hayes Clark – University of Houston

Jennifer Hayes Clark is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and a Research Associate at the Center for Public Policy at the University of Houston. Her primary areas of research interest include American political institutions, public policy, and quantitative research methodology.