Recent immigrants often face barriers to making a living, be it through their limited English or even racial prejudice. Many respond by setting up their own businesses, often in minority neighborhoods. Using data on nearly 5,000 firms from the early 1990s, Tim Bates and Alicia Robb find that while setting up businesses in minority neighborhoods can be attractive for immigrants because of reduced discrimination and the low capital requirements, there are also significant risks. Comparing businesses in minority and white neighborhoods, they find that those in minority areas have a 29 percent closure rate after four years, compared with 21 percent in white areas, and that they make making less than 2/3rds of the profit of their counterparts in non-minority neighborhoods.

Recent immigrants often face barriers to making a living, be it through their limited English or even racial prejudice. Many respond by setting up their own businesses, often in minority neighborhoods. Using data on nearly 5,000 firms from the early 1990s, Tim Bates and Alicia Robb find that while setting up businesses in minority neighborhoods can be attractive for immigrants because of reduced discrimination and the low capital requirements, there are also significant risks. Comparing businesses in minority and white neighborhoods, they find that those in minority areas have a 29 percent closure rate after four years, compared with 21 percent in white areas, and that they make making less than 2/3rds of the profit of their counterparts in non-minority neighborhoods.

Why do entrepreneurs choose to start small businesses, and locate them where they do? Understanding the opportunities that motivate individuals to become small-firm owners is key to understanding entrepreneurship’s local economic development potential. A vibrant and growing small-business community is one where talented individuals are pulled into entrepreneurship by attractive opportunities.

In the 1980s, a provocative sociological literature emerged that explored the proliferation of small firms owned by immigrants from Asia and Latin America in U.S. cities. The seeming success of immigrant entrepreneurs operating small retail and consumer-services ventures in minority neighborhoods appeared to confirm the opinion that greater entrepreneurial initiative means job creation and a healthier economic climate. Although operating retail and consumer-services firms targeting minority clients was clearly a popular strategy, we are still unsure why entrepreneurs took this route. The academic literature offers many opinions and fragments of evidence, but few conclusions. In new research, we find that while minority businesses owners that target other minorities face low barriers to entry and reduced competition; this comes with a higher risk that their business will experience lower profits or fail.

We first looked at why immigrant and minority entrepreneurs chose to concentrate in low-profit retail and service lines of business within minority neighborhoods. We looked at their motivations by comparing the longevity of firms targeting clients in these neighborhoods to those serving clients in white residential areas. A related objective is to identify specific barriers retarding small-business development in minority-neighborhood environs. Analyzing nationally representative samples of nearly 5,000 young urban small firms drawn from U.S. Census Bureau data from 1988 to 1996, we find that serving local clienteles in minority neighborhoods is associated with increased likelihood of firm closure and low profits, compared to firm outcomes in white neighborhood markets.

Minority neighborhood markets offer attractive opportunities – and risks

Selling to customers of the same race/ethnicity is a natural starting point for immigrant- and minority-business owners. Thus, the black-owned barbershops and beauty parlors in African American residential areas are the most numerous black businesses. Asian-immigrant-owned firms often cater to the product preferences of other Asians, particularly in neighborhoods where recent immigrants congregate. The numerous firms owned by Asian immigrants, however, generate intense competition for the patronage of Asian clients, causing many to opt, instead, to market their products to African American and Latino customers. Minority entrepreneurs often self-select into these markets because consumer discrimination limits the range of businesses that white households will patronize. A key motive encouraging Korean immigrants to locate businesses in African American and Latino neighborhoods is “the lower level of discrimination and hostility compared to white areas”.

Other factors explaining the attractiveness of minority neighborhoods are the low barriers to setting up a business. Store rentals are lower than in nearby white neighborhoods; specialized owner managerial skills are often unnecessary; new venture creation is made easier by low capital requirements. These positive attractions are often complemented by push factors. Whether in entrepreneurial pursuits or salaried employment, immigrant minorities face barriers to making a living: limited English fluency, transferable education and work skills, and racial prejudice often limit their options in the mainstream economy. Disadvantages of operating one’s business in minority neighborhoods, nonetheless, are clear-cut. Because many residents have low, variable personal incomes, internal markets are often weak. These communities, often characterized by high crime rates, bank redlining, and disinvestment in infrastructure, are frequently underdeveloped enclaves within prosperous regional economies. The fiscal capacity of local governments is often fragile and scarce public-sector resources are allocated to priority areas elsewhere.

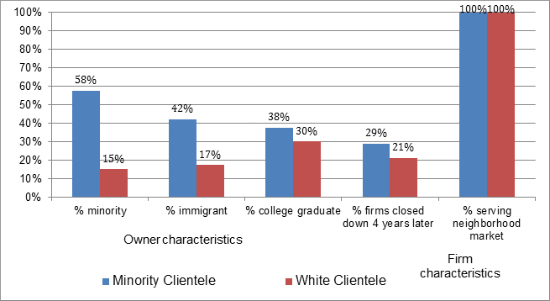

Figure 1 – Traits of Young Small Firms Serving Neighborhood Clients

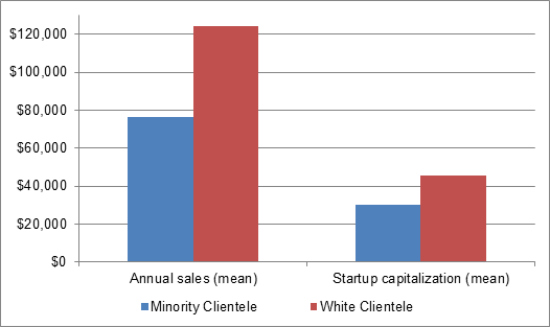

Figure 2 – Young Small Firms capitalization and sales by clientele

Figures 1 and 2 contrast four-year survival rates of minority-clientele-oriented firms to that of their white neighborhood counterparts. The differences are striking: 29 percent of the former and just over 21 percent of the latter had shut down business operations after four years. Perhaps explaining their higher closure rate, minority neighborhood ventures, on average, were smaller and started with less capital investment than white neighborhood firms. Annual sales averaged $76,276 for the former and $124,199 for the latter, while corresponding capital invested at startup averaged $30,302 and $45,259, respectively.

We first tested whether entrepreneurs’ choice of clients – white or minority – made a difference to whether or not the business survived. An established literature predicts increased survival odds for well-capitalized young firms run by owners having the expertise and experience appropriate for operating successful ventures. Highly educated owners are more likely than poorly educated ones to operate viable firms. Owner financial investment in young businesses must be sufficiently large to permit operational efficiencies rooted in economies of scale. Start up capital furthermore, serves as a buffer, heightening the ability of young firms to overcome problems and withstand periods of low demand.

Controlling for differences in firm and owner traits related to small business survival prospects, we found that targeting minority neighborhood household clients increases the likelihood that the firm will go out of business. Next, we compared the profitability of the minority-clientele-oriented neighborhood firms to their nonminority counterparts. The firms that operated in white neighborhood markets were more viable, whether measured by closure or profitability. Our comparative analysis of firm closure patterns in minority and white neighborhoods also implicates limited firm capitalization as an important constraining factor, more so than in nearby white communities. An obvious policy implication is that expanded access to financing would benefit minority-neighborhood firms.

On balance, our findings suggest that the capital, entrepreneurial talent, and infrastructure needed to generate economic revitalization of minority neighborhoods is often in short supply. The most educated firm owners often give up their businesses, complicating revitalization prospects. These deficiencies are rooted in the normal functioning of the U.S. economy, which is why economically depressed minority neighborhoods are normal features of dynamic regional economies.

This article is based on the paper ‘Small-business viability in America’s urban minority communities’ in Urban Studies.

Featured image credit: Andrew Bowness (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1lQps97

_________________________________

Tim Bates – Wayne State University

Tim Bates – Wayne State University

Timothy Bates is distinguished professor of economics emeritus at Wayne State University. He is an authority on minority business development and entrepreneurship.

Alicia Robb – Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation

Alicia Robb – Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation

Alicia Robb is a senior fellow with the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. She is also a visiting scholar with the University of California in Berkeley and the University of Colorado at Boulder. She is the founder and past executive director and board chair of the Foundation for Sustainable Development, an international development organization working in Latin America, Africa, and India. (www.fsdinternational.org).

Is there a newer study? Our MLK street neighborhood has many residents just off the main MLK, it has one open business a Bail Bond service and maybe 4 empty business buildings. The community is showing signs of community pride with routine beautification Projects and clean ups. My question is what kind of business could that small of a community support?