The distortion of facts is nothing new to politics and election campaigns. But, with the rise of the internet and 24-hour news cycle, rumors and conspiracy theories can now spread easier than ever through social networks to reach potential voters. Michael Cacciatore and co-authors look at two examples from the 2008 presidential election campaign to better understand how unsubstantiated rumors can become facts in voters’ minds. They find that values, including political ideology and evangelical Christian status, were primarily responsible for propelling misperceptions about President Barack Obama’s faith, while media use played a more important role in driving the misperception that Sarah Palin, and not Saturday Night Live’s Tina Fey, was responsible for the “I can see Russia from my house” quote. The latter finding lends some credibility to the so-called “lamestream media” effect often espoused by prominent Republican figures.

The distortion of facts is nothing new to politics and election campaigns. But, with the rise of the internet and 24-hour news cycle, rumors and conspiracy theories can now spread easier than ever through social networks to reach potential voters. Michael Cacciatore and co-authors look at two examples from the 2008 presidential election campaign to better understand how unsubstantiated rumors can become facts in voters’ minds. They find that values, including political ideology and evangelical Christian status, were primarily responsible for propelling misperceptions about President Barack Obama’s faith, while media use played a more important role in driving the misperception that Sarah Palin, and not Saturday Night Live’s Tina Fey, was responsible for the “I can see Russia from my house” quote. The latter finding lends some credibility to the so-called “lamestream media” effect often espoused by prominent Republican figures.

Misinformation is inevitable in any political system, but in the U.S., we may have turned the theater of modern politics from a metaphor into reality. In 2008, a chain e-mail went viral during the presidential campaign season. The e-mail presented a biographical sketch of then-Presidential hopeful Barack Obama as a Muslim concealing a radical Islamic past. The e-mail was, of course, baseless and has since been debunked by several fact-checking websites and news organizations. Nevertheless, poll results suggest that a significant portion of the American population believed the rumor to be true during the 2008 presidential election.

Around that same time, then–Alaska governor Sarah Palin rose to prominence as the Republican Party’s candidate for vice president. In September 2008 Palin sat down with Charles Gibson of ABC News for her first interview as the vice-presidential nominee. When asked what insights she had gained by governing a state that was so geographically close to Russia, she responded, “They’re our next-door neighbors, and you can actually see Russia from land here in Alaska, from an island in Alaska.” Two days later, in a parody of Palin on Saturday Night Live, the comedian Tina Fey delivered the now-famous “I can see Russia from my house” line. Fey’s impersonation was an instant hit, garnering millions of views online, and spawning the so-called “Fey effect” related to citizen voting preference.

Our survey revealed that one in five Americans still believe that President Obama is a Muslim (not a Christian), while almost seven in ten Americans mistakenly think Palin (and not SNL’s Tina Fey) was the first to say “I can see Russia from my house.”

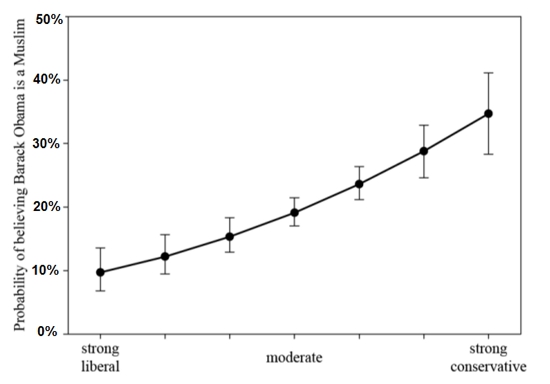

Pundits have long blamed the highly polarized political climate in the U.S. for misperceptions among voters. And, when it comes to the misperceptions surrounding Obama’s faith, this may be true. Even after controlling for the effects of demographic and media use measures, Republicans in our sample were 2.5 times more likely than Democrats to believe that Obama is Muslim (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Relationship between political ideology and the likelihood of believing that Barack Obama is a Muslim

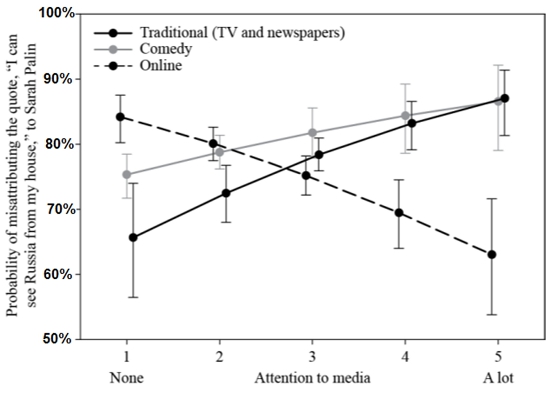

In contrast, misperceptions about who first said “I can see Russia from my house” were much more widespread and stable across ideological fault lines. Almost three quarters of the American population falsely attributed the statement to Palin. And much of the blame, it appears, goes to late night political comedies, such as The Colbert Report and The Daily Show. After controlling for other factors, including demographics and media use, heavy viewers of late night TV comedy had a probability of believing that Palin was the first to say “I can see Russia from my house” that was almost 8 percentage points higher than that calculated for lighter viewers.

Perhaps more alarming, neither knowledge nor traditional news media use helped correct this misperception related to Palin. In fact, heavy traditional news media users were nearly 14 percentage points more likely than light users to think Palin was responsible for the quote. And, while the least politically knowledgeable survey respondents (as assessed through a battery of true/false knowledge questions) had a 28 percent probability of believing that Palin made the statement, that probability jumped to 86.4 percent among the most knowledgeable.

Fortunately, there is a silver lining: Online news consumers were more likely to get their facts straight. Heavy users of online news media were 14 percentage points less likely than lighter online news users to falsely attribute the statement to the former Alaska governor (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Relationship between attention to media (traditional, online, and comedy) and the Likelihood of misattributing the statement, “I can see Russia from my House,” to Sarah Palin.

Some may interpret these findings as yet another indictment of the dysfunctional “lamestream” media spectacle that surrounds our modern elections. And there may be some truth to that sentiment. We all observe the political theater in Washington indirectly through the lens of the media. And our findings show that misinformation about politicians can become fact in voters’ minds if it is repeated often enough in news and entertainment sources. The one upside is that there seems to be little partisan bias to the misperceptions about Palin. In fact, even journalists seem to have a hard time telling Tina Fey and Sarah Palin apart. Indeed, Fox News had to apologize for accidentally using a stock photo of Tina Fey in a story about Palin’s potential presidential bid.

What is more disconcerting is that we may be moving toward a political world where our beliefs are shaped not by what is actually true, but instead by the pseudo-realities created by hyper-partisan talk shows, political pundits, and mainstream media. The informed and deliberative electorate that the Founding Fathers dreamt of may never have existed. But until recently, we also never had a media environment in this country that was so successful at creating the polar opposite of what they had in mind.

This article is based on the paper “Misperceptions in Polarized Politics: The Role of Knowledge, Religiosity, and Media,” in PS: Political Science & Politics.

Featured image credit: Travis (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1m93QVF

_________________________________

Michael A. Cacciatore – University of Georgia

Michael A. Cacciatore – University of Georgia

Michael A. Cacciatore is an assistant professor in the department of advertising and public relations at the University of Georgia.

Sara K. Yeo – University of Utah

Sara K. Yeois an assistant professor in the department of communication at the University of Utah.

Dietram A. Scheufele – University of Wisconsin-Madison

Dietram A. Scheufeleis the John E. Ross Professor in Science Communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Honorary Professor at the Technische Universität, Dresden, Germany.

Michael A Xenos – University of Wisconsin-Madison

Michael A Xenos is an associate professor in the department of communication arts at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Doo-Hun Choi – University of Wisconsin-Madison

Doo-Hun Choiis a doctoral candidate in the department of life sciences communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Dominique Brossard – University of Wisconsin-Madison

Dominique Brossardis Professor and Chair in the department of life sciences communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Amy B. Becker – Loyola University Maryland

Amy B. Beckeris an assistant professor in the department of communication at Loyola University Maryland, in Baltimore.

Elizabeth A. Corley – Arizona State University

Elizabeth A. Corleyis an associate professor in the school of public affairs at Arizona State University.

Good read. The misperception concerning Palin was obviously not great for her. But it’s quite sad that it should even matter to people that Obama might be a Muslim – and worse still, that the misperception has negative implications for him.