In 2010, over 3 million children were suspended from U.S. schools, with black and Latino youth disproportionately affected. In new research, Brea L. Perry looks at the consequences of what has become a widespread punishment for young adults. By using records of school suspensions and academic achievement, she finds that suspensions are used as a punitive response to negative behavior, rather than to keep schools safer, and that their use does not improve the learning environment for any students. She also finds that suspensions are particularly harmful to students’ academic achievement if they are used without restraint and in schools with lower levels of student violence.

In 2010, over 3 million children were suspended from U.S. schools, with black and Latino youth disproportionately affected. In new research, Brea L. Perry looks at the consequences of what has become a widespread punishment for young adults. By using records of school suspensions and academic achievement, she finds that suspensions are used as a punitive response to negative behavior, rather than to keep schools safer, and that their use does not improve the learning environment for any students. She also finds that suspensions are particularly harmful to students’ academic achievement if they are used without restraint and in schools with lower levels of student violence.

In the past decade, critics have condemned the use of suspension as a punishment in schools, citing adverse consequences for suspended students and its ineffectiveness as a deterrent for future misbehavior. However, many parents, teachers, and school administrators continue to defend suspension and other disciplinary policies that exclude offending students from classrooms on the grounds that they create a safe and ordered learning environment for rule-abiding students. According to this rationale – tantamount to sacrificing a few for the good of many – the benefits of exclusionary discipline policies for the majority of students outweigh the risks for “bad apples.” In fact, mounting evidence calls this utilitarian argument into question. School environments that are excessively or inappropriately punitive can have negative collateral effects on all students, even those who have never been suspended.

There are alarming parallels between education and criminal justice in America. Analogous to the criminal justice system, current school discipline practices are invasive and excessively punitive, reflecting a growing crime control approach to student misbehavior. Indeed, schools have borrowed criminal justice techniques of surveillance, placing security cameras, metal detectors, and uniformed police officers in hallways. Zero tolerance policies mimic rigid legal guidelines, requiring automatic suspension or expulsion for specified offenses, and remanding students to police custody for law violations on school grounds. These trends have resulted in a doubling of school suspension rates since the 1970’s. Over 3 million children were suspended from U.S. schools in 2010 – a staggering 1 in 6 African American children and 1 in 20 white children.

Being suspended from school has devastating consequences for children, initiating a trajectory that has been called the school-to-prison pipeline. Suspension is related to low academic achievement, affecting standardized test scores and grades, as well as dropping out of school. In fact, suspended students are three times more likely to drop out than non-suspended students, and dropping out is associated with a three-fold risk for incarceration. Overreliance on suspension, which disproportionately affects black and Latino youth, has been cited as one mechanism contributing to the mass incarceration of people of color in America.

Suspension also takes a psychological toll on children and adolescents. By and large, students who have been suspended feel angry and unfairly punished – not remorseful – about their suspension. This in turn often leads to a weakening of school bonds and disinvestment in education. Feeling unjustly persecuted calls into question the legitimacy of school authority figures and systems of discipline, undermining students’ sense of responsibility to follow the rules during a critical period of social development.

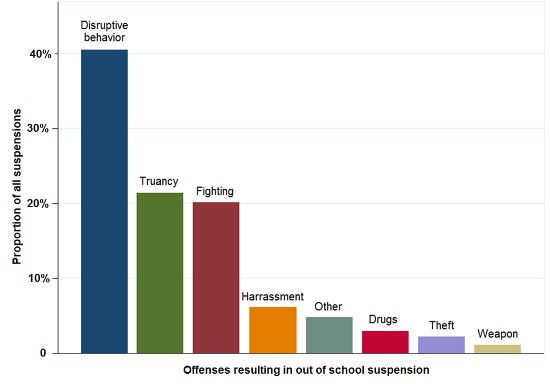

It is easier to understand this cycle of resentment and misbehavior when you consider another troubling development in school discipline – increased use of suspension to address insubordination and other minor infractions. Figure 1 shows this pattern, using records from one racially and socioeconomically diverse school district in the southern United States that serves over 40,000 youth. This study was commissioned by the Children’s Law Center, Inc., in cooperation with the district, to understand mechanisms of racial discipline disparities. The bar graph depicts offenses resulting in out of school suspension. A large percentage of suspensions are for disruptive behavior (41 percent), truancy (22 percent), and fighting (20 percent), while more serious and threatening violations like possession of a weapon or drugs result in less than 1 percent or 3 percent of suspensions per year, respectively.

Figure 1 – Proportion of suspensions attributable to eight types of offenses in one large urban American school district

In short, suspension is rarely used for the purposes of keeping schools safer – an outcome that might arguably justify the negative outcomes experienced by suspended youth. Rather, suspension is used liberally as a punitive response to offenses that can be effectively managed through peer mediation, counseling, and other interventions. This naturally provokes questions about the broader impact of contemporary disciplinary policy in American schools. It led us to wonder whether the psychological effects of an excessively punitive environment might be bleeding over into the student body as a whole and ultimately doing more harm than good.

This is precisely the pattern we identified in our research using standardized tests scores as a measure of student academic achievement. We used only non-suspended middle and high school students in our sample to tease out the effects of personally being suspended from the influence of the disciplinary environment. We found an inverse relationship between the number of suspensions that occurred during the course of a semester and non-suspended students’ percentile scores on end-of-semester reading and math evaluations. Because this pattern could be caused by the level of disruption and violence in the learning environment rather than suspensions themselves, we controlled for the number of instances of disruptive behavior, drug violations, and violent incidents during the same time period. We found the same result – contrary to utilitarian arguments justifying the use of exclusionary discipline for the greater good of all students, suspension does not appear to improve the learning environment for anyone.

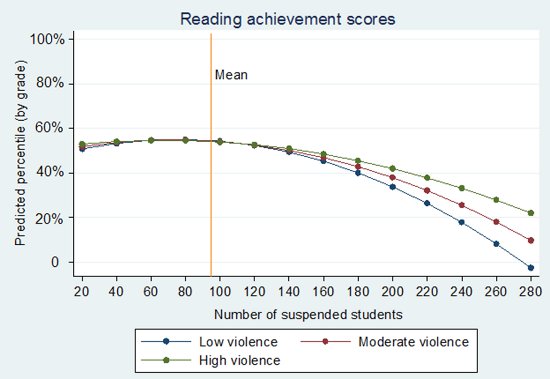

Digging a bit deeper into this finding revealed two important nuances. First, as shown in Figure 2, the relationship between the disciplinary environment and student academic achievement is nonlinear. Exclusionary discipline only becomes harmful when schools are above average in their use of suspensions. Students in schools with suspension rates at the district mean score in the 54th percentile on standardized reading assessments. In contrast, at two standard deviations above the mean level of suspension, the average student performance is at the 33rd percentile in reading. We found a nearly identical pattern for math scores. In other words, excessively punitive environments impede student success, but using suspension selectively and with restraint has no impact, at least among students who were not suspended.

Figure 2 – Effects of school-level suspensions on reading achievement scores among students not suspended

Second, our data show that the strength of the effect of disciplinary environments on student achievement depends on the level of violence in a school. Figures 2 depicts the effects of number of suspensions at three levels of school violence, measured by the number of incidents of fighting, assault, weapons possession, and similar: High (one standard deviation above the mean), moderate (mean), and low (one standard deviation below the mean). Excessive use of suspension is related to poorer academic achievement in all types of schools. However, punitive environments are most harmful to student success in the safest schools (i.e. low violence), where harsh discipline policies are the least justifiable.

Together, these findings provide some insight into potential mechanisms underlying the negative effects of suspension on youth who are not directly punished. Discipline serves broader symbolic, cultural, and affective functions that extend well beyond the specific act of suspension. Enforcing reasonable boundaries communicates meanings about school and societal values and norms, and makes children and adolescents feel secure. In contrast, punishment enacted too zealously could undermine the legitimacy of school rules and those who enforce them, creating a psychological wedge between students and their teachers and administrators.

Ethnographic work in education verifies that an overly punitive school environment can subvert genuine institutional authority and create student apathy, anxiety, and disconnection. In these contexts, all students operate under the same oppressive regime – walking through metal detectors on their way into school or passing uniformed police officers in the hallway. Further, when students are suspended unjustly, that information spreads through peer networks, shaping the attitudes and emotions of the punished and non-punished alike. Rule abiding students operate under a constant threat of surveillance and redefinition as troublemakers, causing an overarching sense of anxiety that radiates throughout punitive schools. Thus, excessive and inappropriate use of discipline can undermine the optimal learning environment that it was meant to create, unintentionally subverting educational goals.

Fortunately, the tide seems to be turning against exclusionary discipline. Some schools are beginning to experiment with suspension diversion programs and other alternatives. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Education released fairer and less punitive school discipline guidelines, directing school administrators to use exclusionary discipline only as a last resort. Safe, effective learning environments must ultimately come from supportive school relationships, not “tough on crime” policies that alienate students from one of the most important socializing institutions of their lives. Researchers and child advocates have argued that contemporary disciplinary policies create winners and losers, often along racial and socioeconomic lines. Our research suggests that there are no winners.

Featured image credit: Medill News21 (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of U.S.App– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1F9CoQD

_________________________________

Brea L. Perry – Indiana University, Bloomington

Brea L. Perry – Indiana University, Bloomington

Brea L. Perry is an Associate Professor of Sociology at Indiana University, Bloomington and an affiliated faculty of the Indiana University Network Institute. Her research focuses on the intersections of medical sociology, biosociology, and social networks. Brea Perry’s recent research has examined the interrelated roles of dynamic social networks, peer and family relationships, social structure, culture, and biological systems in disease etiology and the illness career. She has focused largely on mental illness and at-risk youth, and has a strong interest in longitudinal research, dynamic social processes, and quantitative methods.

1 Comments