Recent years have seen a paradox develop in the public’s attitude towards politics – while they are against legislative gridlock; they are unwilling to compromise on getting what they want out of politics. In new research, Lilliana Mason investigates the trend towards ideological ‘sorting’, where people identify more with the political party that matches their ideological identity. She finds that while party identification may be becoming stronger, divisions on specific issues are still relatively small. She writes that that while people may agree on many issues, their ‘social polarization’ on partisanship means that they dislike and distrust one another, making political compromise difficult.

Recent years have seen a paradox develop in the public’s attitude towards politics – while they are against legislative gridlock; they are unwilling to compromise on getting what they want out of politics. In new research, Lilliana Mason investigates the trend towards ideological ‘sorting’, where people identify more with the political party that matches their ideological identity. She finds that while party identification may be becoming stronger, divisions on specific issues are still relatively small. She writes that that while people may agree on many issues, their ‘social polarization’ on partisanship means that they dislike and distrust one another, making political compromise difficult.

In a December Pew Poll, 71 percent of Americans believed that a failure of Democrats and Republicans to work together would harm the nation “a lot.” And on a number of issues, Democrats and Republicans generally agree on what should be done. For instance, majorities of both parties think the minimum wage should be increased and that background checks on gun purchases should be required. Unfortunately, neither side wants their own party to compromise to solve the nation’s problems. As Pew reports, “both liberals and conservatives define the optimal political outcome as one in which their side gets more of what it wants.” This is a paradox in which gridlock is seen as dangerous, while its causes are fully supported by American partisans.

Why would Americans oppose gridlock and compromise at the same time? My new research provides some clues. Mainly, I found that American political identities are capable of driving a powerful tribal loyalty, particularly when they are very strongly aligned. I call this “social polarization,” and it is defined by intolerance, anger, and heightened political activity, even in the absence of issue-based disagreements. In other words, when partisan and ideological identities are lined up, partisans behave in more team-based ways, even if they agree on substantive issues.

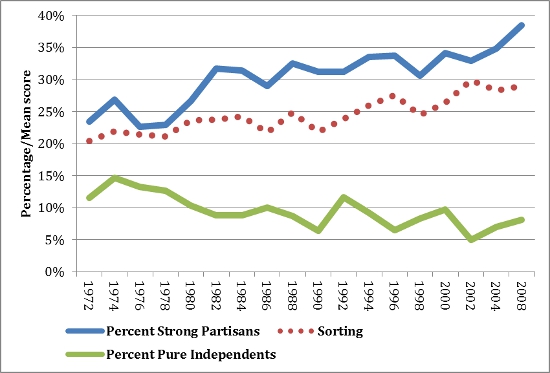

Democrats in American politics have grown more liberal and Republicans have grown more conservative since the 1970’s. This is what political scientists generally refer to as “sorting”. However, this ideological sorting doesn’t simply mean that Republicans and Democrats disagree more than before. In fact, Americans can more strongly identify with the groups “liberal” and “conservative” without actually being very extreme in their issue positions. And this is what has been occurring in American politics.

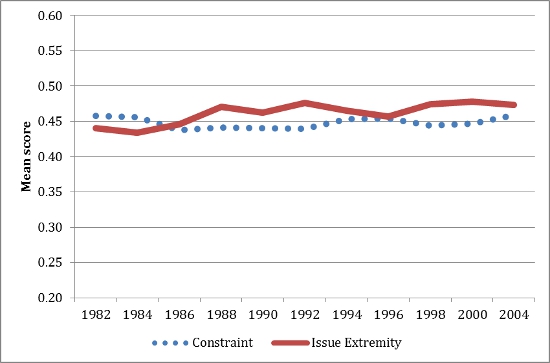

For instance, drawing on data from the American National Election Studies, Figure 1 shows increasing levels of strong partisanship and partisan-ideological sorting, while Figure 2 shows that issue positions simply haven’t increased to the same degree, whether measured as the average extremity of 6 issue positions, or the constraint (ideological consistency) between them.

Figure 1 – Partisan Strength and Sorting, 1972–2008 (0–1 scale)

Figure 2 – Mean Issue Extremity and Constraint, 1982–2004 (0–1 scale)

The alignment between party and ideological identities is causing American partisans to behave in ways that are more tribal than rational. Even when we agree on policy outcomes, we feel prejudiced against and angry at our opponents, and we want our team to win.

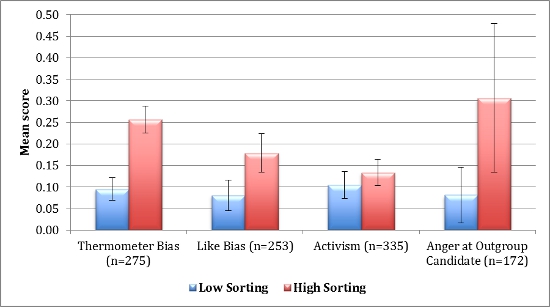

One way to show this is to use a “matching technique” that essentially chooses individuals that are as similar as possible on a large number of attributes, and then tests the effect of one small change. In my research, I matched individuals on their issue positions as well as their education, age, sex, race, location, religiosity, and ideological identity. The only thing I allowed to move was how well their partisanship lined up with their ideological identity. Figure 3 shows the difference in levels of social polarization between these people who are largely identical in everything including issue positions, but different in their level of sorting.

Figure 3 – Mean Social Polarization: Matching on Issue Positions and Ideology

Note: Data from the American National Election Studies. Bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals.

In “thermometer bias” (the difference between feelings toward the two parties), “like bias” (the difference between the number of likes and dislikes mentioned for each party), political activism, and anger at the opposing presidential candidate, these identical people who agree on most issues are all much more biased and angry, and slightly more active, when they simply hold a well-aligned set of partisan and ideological identities. They agree on issues, and are quite similar demographically, but they truly dislike and distrust each other.

The story behind this unreasonable behavior is in fact much more logical than it seems at first glance. My research is heavily influenced by some long-standing research in social psychology that explains the origins of this apparently paradoxical behavior. In the late 1960’s, social psychologist Henri Tajfel and his colleagues ran a series of experiments in which they randomly gave subjects meaningless group labels (ie. overestimators and underestimators). They then asked the subjects to allocate money in one of two ways. Either everyone receives the maximum amount, or their own group receives less than the maximum, and the other group receives even less than that.

Tajfel expected most subjects to choose the common good of the whole over team victory, particularly because these were meaningless groups with no prior conflict between them. He was wrong. He was surprised to find that when people are given a choice between the greater good and team victory, “it is the winning that seems more important to them.”

Again and again, in every conceivable iteration of this experiment (and there have been many), people privileged the group to which they had been randomly assigned, often at the expense of the population as a whole. One experiment even found that people rated their own meaningless group as good and the other group as bad faster than they could consciously know what they were doing. We want our group to win, and that desire happens in the blink of an eye.

Why are group labels, even meaningless ones, so powerful? Because being part of a group helps us to understand who we are and how we fit into our world. We are hard-wired to feel like losers if our group loses, and to feel like winners if our group wins. We are also hard-wired to avoid feeling like losers at all costs.

Now take those meaningless group labels and make them meaningful. Call them Democrats and Republicans. It turns out that those eye-blink reactions to group labels apply to Democrats and Republicans too. Even worse, call them Liberal Democrats and Conservative Republicans. When social identities converge, social psychology research shows that prejudice, intolerance, and anger result. The more our identities converge, the less we like outsiders, and the more important our groups become to us.

All of the political arguments over Obamacare, taxes, and abortion (but also minimum wages and background checks) are built on a base of automatic and primal feelings that compel us to believe and to demand that our group is the best, regardless of the content of the discussion. A partisan prefers his or her own team partly for rational, policy-based reasons, but also for primal, involuntary, self-defense reasons. These latter reasons are not petty, they are very natural protective mechanisms. Unfortunately, this can cause unreasonable behavior and an oversized emphasis on the goal of victory. As our identities grow more sorted, the more likely we are to exhibit this primal behavior.

Reasoned policy opinion and blind victory-chasing have always been the angel and the devil sitting on the shoulders of American voters. The relative power of each has fluctuated over time. But as our partisan and ideological identities have converged, team spirit has pulled ahead of policy attitudes in driving American politics. Until our political identities weaken or fall out of alignment, American partisans will continue to choose victory over the greater good, even at the expense of their own interests.

This article is based on the paper ‘“I Disrespectfully Agree”: The Differential Effects of Partisan Sorting on Social and Issue Polarization’, in the American Journal of Political Science.

Featured image credit: Trei Brundrett (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1zNOGVS

_________________________________

Lilliana Mason – Rutgers University

Lilliana Mason – Rutgers University

Lilliana Mason is a Visiting Scholar at Rutgers University. Beginning in the fall of 2015 she will be an Assistant Professor at the University of Maryland, College Park. Her research focuses on political identities and political psychology.