In 2008, Barack Obama was elected as America’s first urban president, with large victories in the biggest urban centers. What lessons should 2016’s potential candidates be taking from these victories? In new research which examines election results in 92 ‘core’ counties – which accounted for 35 million votes in 2012 – Joshua D. Ambrosius finds that President Obama identified with urban voters in the way that Republicans could not. He argues that this is not likely to change in the near future, as the urban electorate is identifying less and less with the Republican Party, which is doing little to claim cities as their own.

In 2008, Barack Obama was elected as America’s first urban president, with large victories in the biggest urban centers. What lessons should 2016’s potential candidates be taking from these victories? In new research which examines election results in 92 ‘core’ counties – which accounted for 35 million votes in 2012 – Joshua D. Ambrosius finds that President Obama identified with urban voters in the way that Republicans could not. He argues that this is not likely to change in the near future, as the urban electorate is identifying less and less with the Republican Party, which is doing little to claim cities as their own.

Bill Clinton claimed the presidency in 1992 with his famous campaign mantra, it’s “the economy, stupid.” No doubt the Republicans and Mitt Romney believed that the weak economy was their ticket to unseating the nation’s first urban president in November of 2012. We all know how that turned out. Despite the conventional wisdom at the time, identity trumped the economy in 2012 in the nation’s largest urban centers; and it was the strength of this urban advantage that helped carry President Barack Obama—the nation’s first urban president—to an easy Electoral College victory and an eked-out popular vote. The parties and primary voters should carefully consider how well the candidates for 2016 will play to urban voters—and the candidates should learn from Obama’s urban successes.

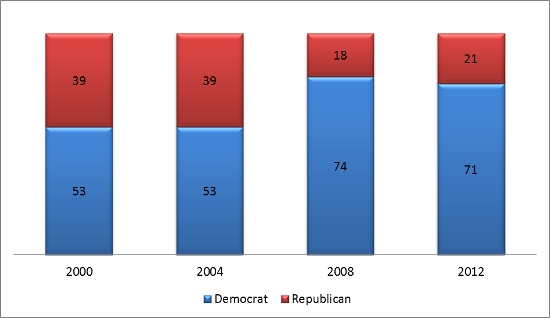

The Democratic urban advantage creates an image most people are familiar with: a national map of county election results that is very red with pockets of urban blue, many of which nonetheless dwarf the red counties’ in population. But just like states come in two colors, there are “blue cities” and “red cities.” While Obama handily defeated Romney in the central cities across the U.S., nearly one-quarter of these cities’ counties still supported Romney. This total carried by Romney, however, is down 50 percent from the number George W. Bush won eight years prior. The demographics of red and blue cities are predictable, but Romney’s red cities surprisingly had better economic indicators: lower unemployment and higher shares of manufacturing jobs.

It was the politics of identity—not economic performance—that produced an urban landslide for Obama. The Republican Party predicated its election fortunes on its candidates’ supposed economic smarts—Romney in the private sector, Ryan in the public—rather than direct appeals to identity, a strategy that failed to produce victory and will haunt the party for the foreseeable future. The Democrats too must worry about the urban appeal of the candidate who takes Obama’s mantle. Can a Hillary Clinton or Joe Biden woo urban voters the way that Obama clearly did?

Obama painted the towns blue

I analyzed 92 “core” counties—those containing the central cities of America’s major metropolitan areas with populations of 250,000 or more—in each of the past four elections (2000-2012). The sample includes counties containing megacities like Chicago and Los Angeles, but also mid-sized cities like Louisville, Kentucky, and Dayton, Ohio. An analysis of core counties is not the same as restricting vote totals to within city limits, but election data is reported at the county level and other county-level data is easily obtainable.

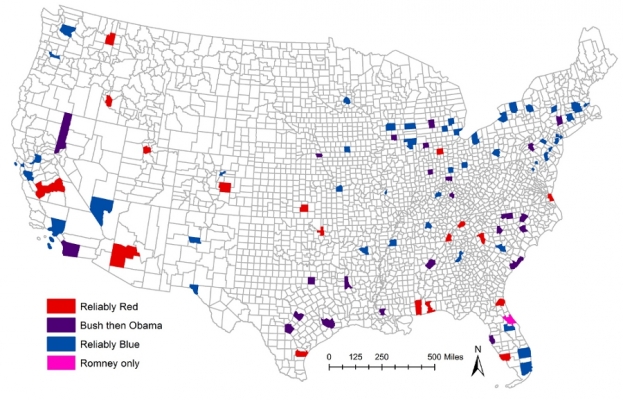

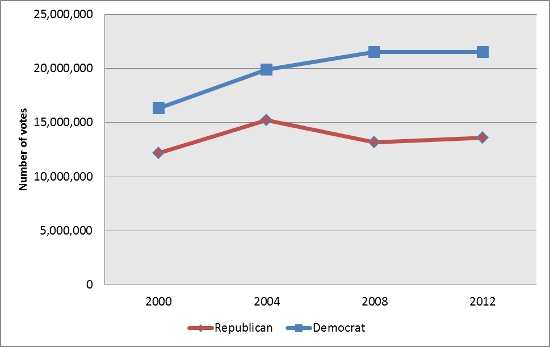

These 92 core counties—just 3 percent of all counties—accounted for 35 million votes in 2012, or over one-quarter of the electorate, of which almost two-thirds went for Obama. Remarkably, Bush was able to carry 39 of these 92 counties with about 43 percent of the total vote in both 2000 and 2004. In 2008, Barack Obama limited John McCain to just 18 counties and 38 percent of votes. In 2012, Mitt Romney was able to increase this total minimally to 22 counties and 39 percent of votes.

Figure 1 – Total Core County Votes by Party, 2000-2012 (for 92 Counties in the Sample)

Figure 2 – Core Counties Won by Presidential Party, 2000-2012 (of 92 in the Sample)

I mapped the counties under analysis and color-coded them by winner. Several core counties are reliably red across all four elections, including those of the Jacksonville, Florida; Phoenix; and Salt Lake City metro areas. Counties that were red under both Bush elections but blue under Obama include the cities of Dallas, San Diego, and Cincinnati. Ones that went blue in 2008 but red in 2012 were few, including Omaha, Nebraska, and Grand Rapids, Michigan. Despite a bad economy, Romney was only able to flip four counties to the warmer shade.

Figure 3 – Map of Core Counties Won by Presidential Party, 2000-2012 (click to enlarge)

What makes an urban county blue or red?

What are some of the differences between core counties won by Romney and those won by Obama? Not surprisingly, Obama’s blue counties have higher levels of minorities, young people under 30, people with a college degree, and same-sex households. Blue counties also have lower proportions of veterans and followers of culturally conservative religious traditions, including evangelical Protestants and Mormons. Obama’s counties, on average, boast nearly doubled populations and 12 percent higher median incomes. Interestingly, Romney’s red counties had slightly lower September 2012 unemployment rates (7.2 percent vs. 7.9 percent), the last announced before the election, and higher shares of manufacturing jobs as a proportion of total employment (8.7 percent to 7.9 percent). In other words, Romney’s counties actually experienced better economic performance under an Obama presidency.

Statistical analysis shows that the socio-demographic and cultural identity variables steered the urban vote. Together these variables account for approximately three-quarters of the variation in the vote proportion for either candidate in these counties. The two economic variables, unemployment and manufacturing, together account for less than 8 percent of the variation in candidate support. (The manufacturing variable may itself be more of an identity variable too if it proxies union membership.) In other words, our identities color how we see the economic data and feel its effects when voting for president.

Identity politics are alive and well

I draw three conclusions from this analysis:

1) The practice of identity politics is alive and well, despite what was written after Obama’s first election. The president identifies with the urban electorate in a way Republicans cannot and likely will not anytime soon. Obama’s appeal to urban populations is greater than recent Democratic nominees Al Gore and John Kerry. Obama’s identity cut the GOP’s previous urban victories in half and increased the Democratic share of core county votes by 5.2 million over Gore’s total in 2000.

2) The urban electorate is identifying less and less with the Republican Party. President Bush was not an urbanophile by any stretch of the imagination, but he carried 20 more core counties than McCain and Romney. Is this demonstrative of a societal trend, evidence of Bush “architect” Karl Rove’s genius, or simply because of Obama’s urban appeal? Whatever the reason, the GOP must compensate for this deficiency or risk losing future elections by even greater margins in urban areas. It will require softening their platform’s stances on social welfare policy, immigration reform, and same-sex marriage and diversifying the top of the ticket. This latter strategy might be easier said than done considering African-American former Republican National Committee chairman Michael Steele’s pre-election comment that the GOP is “not ready for folks like me”.

3) While Obama is a definite urbanite, he has not necessarily worked hard to earn the urban vote. Obama attempted to appeal to the nation as a whole over his first four years—a clear, successful strategy to maintain second-term electability. Republicans feared that Obama would use his second term to enact his “real” agenda, one that could have included more emphasis on distinctly urban policy as called for post-election by the National Urban League. But as one observer wrote, Obama’s efforts in this area brought a lot of “hope but not much change.”

Implications for 2016: Can any candidates match Obama’s urban appeal?

Ultimately, the question becomes: who might the parties nominate in 2016 (and beyond) that could appeal to urban electorates like Obama has? Obama appealed to both segments of the urban public: minorities and white liberals. Of the possible Democratic nominees, Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley, the former Mayor of Baltimore, might appeal most to the latter. Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick, who will probably run in the future but not 2016, could appeal to the former—with his geographic ties to Chicago and Boston as well as civil rights experience. The Republicans have no one to speak of with urban credentials. Given his brother’s legacy, I doubt Jeb Bush can increase the Republican share of urban centers to its pre-2008 level.

If the Democratic Party harkens back to 2000 and 2004 in 2016 by nominating Vice President Biden, or another similar white, older man, the party could sacrifice its urban gains under Obama — thus making real urban policy and urban economic performance more important to secure future urban votes. The same may be true for Hilary Clinton—but she does have her husband’s past appeal to aid her. (Although I cannot make claims about Clinton’s urban appeal compared to Obama’s because the 1992-1996 elections were not a part of my analysis.) But in the face of Republican inaction to claim the cities as their own, the Democrats will continue to paint these towns blue—even if the shade is a bit lighter next time around.

This is based on the article “Blue City…Red City? A Comparison of Competing Theories of Core County Outcomes in U.S. Presidential Elections, 2000-2012” in the Journal of Urban Affairs.

This research was also featured in an Atlantic CityLab piece by Richard Florida.

Featured image credit: John W. Iwanski (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1O9Q14k

_________________________________

Joshua D. Ambrosius – University of Dayton

Joshua D. Ambrosius – University of Dayton

Joshua D. Ambrosius is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and Master of Public Administration Program at the University of Dayton in Dayton, Ohio. His research interests include urban and housing policy, regional governance, and religious organizations. His academic work has appeared in such journals as Journal of Urban Affairs, Housing Policy Debate, American Review of Public Administration, Journal of Urbanism, and Local Environment.