Shortly after his election President Obama nominated former Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, Eric Shinseki, to head the beleaguered Department of Veterans Affairs. Despite Shinseki’s reputation as a transformational leader, he largely failed to transform the Department of Veterans Affairs, and resigned in early 2014. Montgomery Van Wart writes that Shinseki’s example shows how difficult it is to be a transformational administrative leader, and the difficulties there are in evaluating them.

Shortly after his election President Obama nominated former Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, Eric Shinseki, to head the beleaguered Department of Veterans Affairs. Despite Shinseki’s reputation as a transformational leader, he largely failed to transform the Department of Veterans Affairs, and resigned in early 2014. Montgomery Van Wart writes that Shinseki’s example shows how difficult it is to be a transformational administrative leader, and the difficulties there are in evaluating them.

Following a long period of continuity, the public sector in the U.S. entered an age of change in the 1990s, a trend that appears likely to continue for the foreseeable future. Time and time again it has been seen that the quality of implementation is as important as policy decisions themselves in making great changes work. It follows then, that transformational leaders are needed, not only at the policy level, but at the administrative level as well.

When President Barack Obama gained the White House in 2009, after having been a member of the Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, he dubbed the transformation of the Department of Veterans Affairs his third most important priority after overhauls of the healthcare and financial systems. The agency had been struggling for decades, and Obama wanted to see care expanded (serving more veterans) and speed of access (which was highly criticized) improved. He chose the former four-star general, Eric Shinseki, who seemed ideal but who turned out badly.

Eric Shinseki was the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army from 1998 to 2003. During that time he was the lead person in designing the army’s relatively radical reorganization. The Army moved from conventional warfare that relied on large, heavily-equipped divisions, to one composed of “modular” brigades that could move independently, and in which some would be lightly armored for strategic deployment as needed. While Shinseki’s interactions with his political superiors during the Bush Administration were very poor because he publicly disagreed with them about the size of the military footprint necessary after army incursions for peace keeping and nation building, he did turn out to be correct. Obama felt Shinseki was perfect as a highly decorated war hero, a self-identified transformational leader, a person of great integrity, and someone who knew military culture.

While the ingredients seemed ideal, the outcome showed many deficiencies in his second five-year term as an agency head from 2009 to 2014. Shinseki seemed to start out well with agency-wide reviews, a plan for improvement, and budget enhancements to include more veterans and services. Employee morale increased and military service organizations were happy. However, many problems accumulated over time. He made a number of management errors as a non-expert such as ordering improvements in standards without additional administrative support or verification. He was unaware of extensive performance lapses. He let pay and training languish even though a largely medical agency cannot compete and collaborate without it. Longtime employees increasingly felt ignored by the executive leadership team. While his integrity was unblemished, his persona was formal, distant, and uninspiring, and a culture of hierarchy, rules, and “demands” crept in. Finally, while his initial planning was relatively good, Shinseki continually expanded the scope of the agency without sufficiently addressing its administrative capacity to serve the complex and vast medical needs of millions of veterans. Because he greatly expanded the number of people using the system, wait times for appointments and benefit reimbursements soared rather than shrank. Finally, when the political landscape between the parties became intensely partisan over veterans’ benefits, rather than being able to keep his agency and himself neutral, he was used as political fodder in newspaper headlines to attack the President because of agency lapses he had overlooked.

- Secretary of Veterans Affiars Eric Shinseki testifies before a joint session of the House Armed Services Committee and the House Committee for Veterans Affairs at the Rayburn building in Washington D.C., July 25, 2012. DoD photo by Erin A. Kirk-Cuomo (Released)

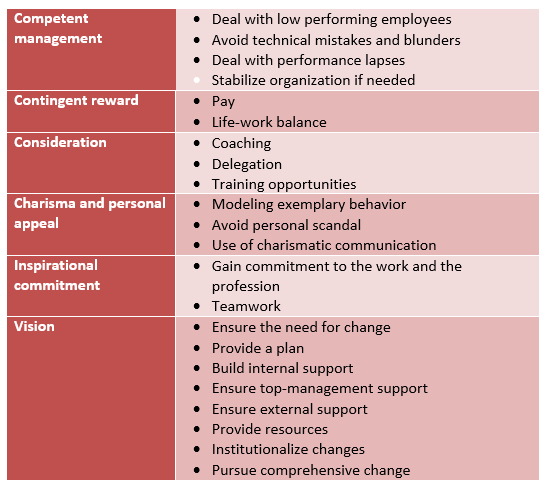

So what do administrative leaders need to do to be successful as transformers, and similarly, how can we evaluate them given the complexities of the demands placed on them? Using a well-respected theory of Bernard Bass, we can state that six major aspects or competency clusters need to progressively build on one another in order to be a “full-range” leader capable of high performance. This full-range begins with “competent management” that includes dealing with low performing employees, avoiding future technical mistakes and blunders, addressing performance issues, and stabilizing the organization when in crisis. “Contingent reward” is based on the exchange between employers and employees and includes addressing pay and life-work balance. “Consideration” is demonstrated by ensuring coaching, delegation, and training opportunities, among others. “Charisma,” or simply trustworthiness, is exhibited by the leader modeling exemplary behavior, avoiding personal scandal, and using charismatic communication via symbols, evocative language, and personal dynamism. “Inspirational commitment” is demonstrated by pride in the shared work on one hand, and teamwork on the other. The final factor is “vision” which includes the technical steps of planning and implementation of change. This relatively comprehensive list of 22 factors is provided below.

Table 1 – Transformational administrative leaders tend to be proficient in 22 factors

In reality, few administrative leaders have the circumstances or desire to be truly transformational. Not surprisingly, to be a great transformational leader in a senior administrative position is very difficult and, ultimately, rare. Yet, administrative leaders can be at least partially transformational under select circumstances and with sufficient will, skill, and some luck. The evaluation of Shinseki as Secretary of the Veterans Administration is an example of both how difficult it is to be a transformational leader, and how to evaluate that leader using a variety of specific factors before moving to a holistic judgment. It is challenging because he ranked well in some of the 22 factors such as moral integrity and initial planning, but poor in most of them, despite the competencies he seemed to have for the job.

The job of transformation at the Department of Veterans Affairs was more challenging than Shinseki had anticipated, and it was harder for him to master the details as instinctively as he had in the Army. Indeed, the use of a typical military command style in a civilian agency dominated by a professional health focus was a major aspect of his downfall; he did not adapt his style. In the end, despite progress in policy goals (the expansion of benefits and services), technical difficulties mounted and ultimately erupted. Additionally, Shinseki had not changed the internal culture; rather, it declined substantially during his tenure, with lower morale in general and strains of corruption he did not detect until it was too late. To the degree that Shinseki can be considered a successful transformational leader, it is based on his admirable success in the Army, and not his experience in the VA which, sadly, ended as an embarrassment.

This article is based on the paper “Evaluating Transformational Leaders: The Challenging Case of Eric Shinseki and the VA,” in Public Administration Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1KXAPWy

_________________________________

Montgomery Van Wart – California State University

Montgomery Van Wart – California State University

Montgomery Van Wart is professor in the Department of Public Administration at California State University, San Bernardino. He has served as chair of his department and dean of the College of Business and Public Administration. He has authored nine books, including Dynamics of Leadership in Public Service, Leadership in Public Organizations, The Business of Leadership (with Karen Dill Bowerman), Administrative Leadership in the Public Sector (with Lisa A. Dicke), and, most recently, Leadership and Culture: Comparative Models of Top Civil Servant Training.

Did you look at the previous “turn around” person brought into the VA – by Clinton? Ron Kiser I think was his name. By all accounts he made a real difference, but obviously his changes did not last the distance, and maybe one of the problems is the politicised nature of the VA and its closeness to Congress. peter