It is a common conceit in American politics that urban voters tend to vote for the Democratic Party, while those in rural areas vote for Republicans. In new research, Dante J. Scala and Kenneth M. Johnson find that the truth is not nearly so simple – changes in population and the rural economy have led to the growth of democratic enclaves in ‘recreational counties’ which are dominated by the new rural service and amenity economy. They argue that while at the county level, the ‘big sort’ may be true, if we widen our view, rural America is increasingly looking more politically and demographically diverse.

It is a common conceit in American politics that urban voters tend to vote for the Democratic Party, while those in rural areas vote for Republicans. In new research, Dante J. Scala and Kenneth M. Johnson find that the truth is not nearly so simple – changes in population and the rural economy have led to the growth of democratic enclaves in ‘recreational counties’ which are dominated by the new rural service and amenity economy. They argue that while at the county level, the ‘big sort’ may be true, if we widen our view, rural America is increasingly looking more politically and demographically diverse.

In US politics, rural America has become synonymous with “red” America, dominated by Republican voters. Yet, as our research demonstrates, political commentators mistakenly caricature rural America as a single entity. In fact, rural America is a deceptively simple term describing a remarkably diverse collection of places. It encompasses nearly 75 percent of the land area of the United States and 50 million people. Both demographic and voting trends in this vast area are far from monolithic. Some rural counties, including those with economies based on recreation, have experienced decades of sustained population growth fueled by migration, while farm counties in the heartland continue to lose people and institutions. Republican presidential candidates have generally done well in rural America, but we identify important enclaves of Democratic strength there as well.

Such pockets of rural Democratic strength are particularly important in tightly contested swing states such as New Hampshire, where Democrats have carried the state in five of the last six presidential elections. In New Hampshire, the heart of the Republican base resides in its most densely populated urban counties, Hillsborough and Rockingham, which comprise part of the outer suburban ring of the Boston metropolitan area. It is New Hampshire’s rural counties that have offered critical vote margins to Democratic presidential candidates, from John Kerry to Barack Obama. The existence of such “blue” rural counties is not unique to New Hampshire.

Democratic presidential candidates’ median performance in rural counties has remained under 40 percent since Al Gore’s 2000 campaign. Democrats’ stagnant national performance, however, masks significant variations within rural America. While Democratic presidential candidates’ aggregate performance in rural America remained poor during the last decade, they enjoyed improving prospects in the sections of rural America with an economy based on recreational amenities. In several “swing states” in the Northeast, the South, and the Far West, voters in rural recreational counties have provided Democrats with zones of support within the generally unfriendly environment of rural America.

Even after controlling for demographic factors and the North-South split in our research, we find that the type of economy that dominates a particular rural county affects its partisan tilt. Voters who reside in areas dominated by farming typically favor Republicans. In contrast, Democrats find electorally critical pockets of strength among voters residing in areas dominated by the new rural economy, based on recreational amenities and services. Rural recreational counties have experienced rapid population increase fueled by significant numbers of in-migrants attracted by the quality of life. These migrants bring their political preferences with them. Mobile voters tend to be wealthier and better educated and their presence contributes to a thriving service economy, another source of Democratic strength. Barack Obama’s support in recreational counties was greater than in any other part of rural America, except in counties with significant numbers of African-American voters.

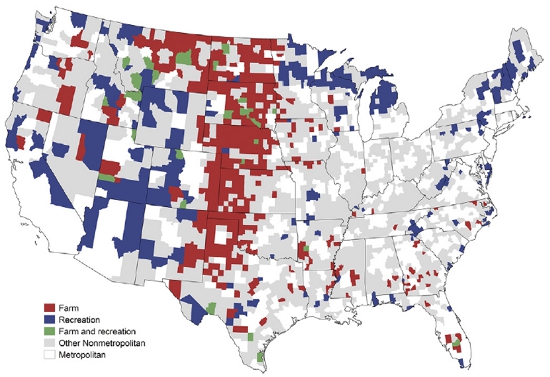

As Figure 1 illustrates, recreational counties are distributed unevenly across rural America, but are concentrated in areas with natural amenities such as lakes and ocean shores, forests, mountains and temperate climates. Though these natural amenities provide the foundation for most recreational areas, they are often supplemented by built amenities such as golf courses, ski resorts and casinos. In contrast, farm counties, where Republican presidential candidates have done the best, are heavily concentrated in the Great Plains, with modest numbers in other regions. The influence of farming and recreation is not limited to these counties though it is more dominant here. In all, the 289 rural recreational counties represent approximately 14 percent of all rural counties and 16 percent of the rural population. The 403 farm counties are 20 percent of all rural counties and include roughly 6 percent of the rural population.

Figure 1 – Nonmetropolitan counites by farm and recreational status

Source: USDA Economic Research Service, 2004.

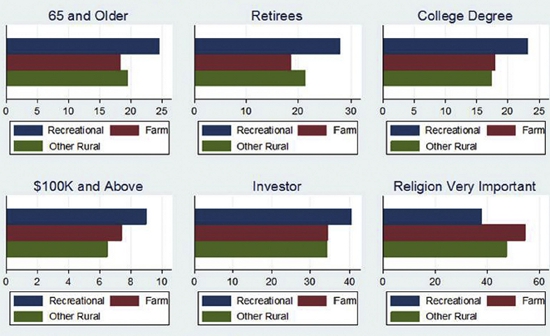

As we look to the future, these recreational counties may become even more influential in key swing states. Population gains in recreational counties have far exceeded those in other rural counties in each of the last two decades. Migration has fueled almost all of this population gain. Both the population and political influence of recreational counties in national elections are likely to increase given their appeal to the 70 million Baby Boomers who will retire in the next two decades. As Figure 2 shows, older migrants in their 50s and 60s find these counties particularly appealing, but family-age migrants are also attracted by economic and employment opportunities. Over the last several decades, these recreational counties have become a bright spot for Democrats within rural America. Our research suggests the residents of recreational counties, on the whole, have a higher median income, and more have graduated from college than their counterparts in other rural counties. In contrast, the average farm county experienced minimal, if any, population gain and lost migrants in each of the last two decades. Education levels tended to be lower than in recreational counties and income levels were roughly equivalent to those in other rural counties.

Figure 2 – Varying demographics of rural America

Source: Cooperative Congressional Election Study

Our research offers both corroboration and corrective to the discussion of the importance of migration and sorting to American electoral geography. On the one hand, the immediately apparent political consequences correspond with the “big sort” argument made by Bill Bishop and others. Survey data document that fast-growing recreational rural counties have become home to a population that is wealthier, better educated, more liberal, and more likely to vote Democratic than their traditional rural counterparts. These counties are distinctive islands on the rural American landscape.

However, while the “big sort” argument suggests that migration leads to greater uniformity in American political life (with Republicans tending to live near other Republicans and Democrats near other Democrats), the appearance of uniformity depends on the size of the political unit examined. There may be less diversity at the county level, but widen the view, and it becomes clear that population changes in recreational counties have led to more, not less, diversity in rural America. At the state level, the growth of recreational counties has helped to create several new “swing states” that are now battlegrounds in presidential elections. In these states, the growth of recreational counties has diminished the political polarization that normally characterizes the urban-rural divide in America. This phenomenon is most pronounced in New Hampshire, the Southwest, and the West Coast states of Oregon and Washington. On the whole, this phenomenon has benefited Democratic candidates, who enjoy these enclaves of rural America which are more sympathetic to their message.

This article is based on the paper, “Red Rural, Blue Rural? Presidential Voting Patterns in a Changing Rural America” in Political Geography.

Featured image credit: Derek Key (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of U.S.App– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1HnplWv

_________________________________

Dante J. Scala – University of New Hampshire

Dante J. Scala – University of New Hampshire

Dante J. Scala is an associate professor in political science at the University of New Hampshire. He has studied the changing political demographics of New Hampshire for more than a decade, and his expertise is recognized locally and nationally. His book with Henry Olsen of the Ethics & Public Policy Center, The Four Faces of the Republican Party, will be published by Palgrave Macmillan later this year.

Kenneth M. Johnson – University of New Hampshire

Kenneth M. Johnson – University of New Hampshire

Kenneth M. Johnson is senior demographer at the Carsey School of Public Policy and professor of sociology at the University of New Hampshire. He is a nationally recognized expert on U.S. demographic trends. His research examines national and regional population redistribution trends, rural and urban demographic change, the growing racial diversity of the U.S. population, and the relationship between demographic and environmental change.