A hallmark of contemporary political campaigns is that most will at some stage ‘go negative’, with attacks against the rival candidate. But what determines when candidates choose to go negative? In new research which looks at Congressional campaigning, Hans J.G. Hassell and Kelly R. Oeltjenbruns find that while candidates in open-seat races tend to begin positively, go negative, and then end positively, challengers and incumbents tend to start negative and more or less stay that way throughout the campaign.

A hallmark of contemporary political campaigns is that most will at some stage ‘go negative’, with attacks against the rival candidate. But what determines when candidates choose to go negative? In new research which looks at Congressional campaigning, Hans J.G. Hassell and Kelly R. Oeltjenbruns find that while candidates in open-seat races tend to begin positively, go negative, and then end positively, challengers and incumbents tend to start negative and more or less stay that way throughout the campaign.

As the 2016 presidential campaign has been unfolding, there has been no shortage of negativity between candidates on both sides. Campaign negativity is not limited to presidential elections, though – in last year’s Congressional elections a number of races went negative, such as in Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District which saw the Democratic candidate, Brad Ashford linked to the early release of an inmate who committed four murders:

But what factors influence the decision of when to ‘go negative’? Although previous scholarship has found that a variety of factors, including the closeness of a congressional race and the status of the candidate as an incumbent or a challenger, affect the volume of negativity over the entire campaign, scholars have not looked at how these factors affect when in the campaign candidates choose to go negative. The traditional narrative of campaign negativity suggests that campaigns should start on a positive note, turn to negativity in the heat of the campaign to discredit their opponents, and then end on a positive note to help reduce negative opinions about their own campaign. Yet, this narrative is based only entirely on anecdotal stories largely gleaned from media coverage.

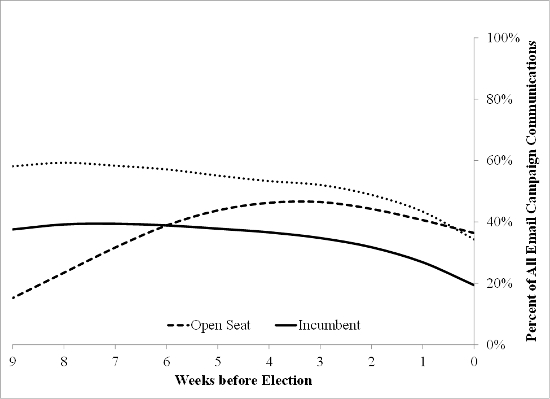

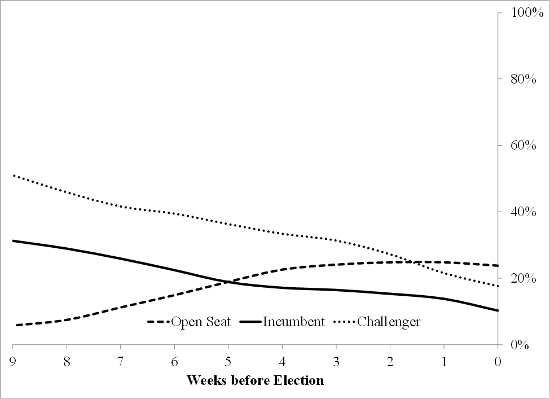

In perhaps the first comprehensive study of the trajectory of campaign negativity we find that this traditional narrative is largely incorrect and, perhaps unsurprisingly, drawn from a small subsample of campaigns more likely to be covered by the media. Using over 1400 campaign emails collected from congressional campaigns in a random sample of 100 congressional districts in the 2012 election we find that incumbents and challengers exhibit similar rhetorical tone dynamics throughout the course of the campaign, dynamics distinct from candidates in open-seat races. As shown in Figure 1, we find that open-seat candidates follow the traditional narrative outlined above. Challengers and incumbents, however, are more likely to start the campaign with high levels of negativity and are less likely to vary the tone of their message over the course of the campaign.

Figure 1 – Negative Campaign Rhetoric Trend by Week

Note: Trends are smoothed using a Lowess smoothing algorithm

We argue that these differences are the result of the unique ‘battlegrounds’ surrounding these two types of electoral races. The battleground for incumbents and challengers necessarily involves a scenario in which one candidate and that candidate’s political record is well known to the public. Battle lines are either known or drawn early because of the record and experience of the incumbent.

The dynamics of negativity exhibited by candidates in open seat races, however, differs significantly. Open-seat candidates and their policy stances are more likely to be unfamiliar to the voting public. As such, it is less likely that either candidate has a clear understanding of the opponent’s policy positions and the grounds on which to base issue attacks. Because of this, candidates must wait for more information before clear lines of attack emerge to allow them to engage in negative campaign rhetoric.

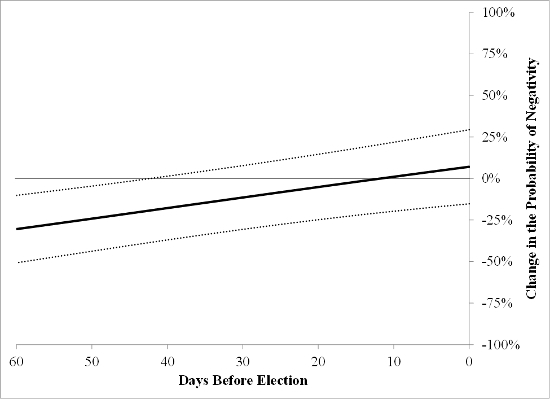

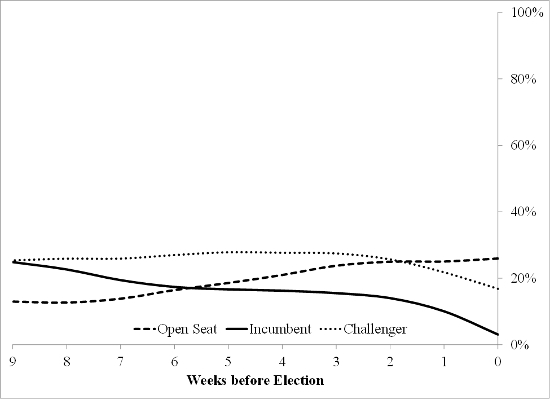

Figure 2 – Marginal Effects of Open Seat Candidacy on Negativity

Note: Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals

Controlling for other election and candidate characteristics, such as competitiveness, candidate quality, gender, and party affiliation, candidates for open seats are almost 25 percentage points less likely to engage in negative campaigning sixty days out from an election compared to challengers as seen in Figure 2. Compared to the marginal effects of other predictors of negativity, being an open seat candidate in the early stages of the campaign reduces the likelihood more than changing the gender of the candidate from male to female (a decrease in the likelihood of negativity by 15 percent). That effect, however, disappears in about twenty days as lines of attack become clearer and negative campaigning in open seat races begins to escalate.

Support for our argument that these differences in the trajectory of campaign negativity are driven by the electoral battleground is evident in the object of negativity in the race. As shown in Figures 3 and 4, this initial positive bent of open-seat campaigns is driven by the relative absence of negativity directed at the opponent’s voting record or policy positions. There is no significant difference in the volume of negativity directed at the opponent’s character or other personal characteristics between open seat races and races with an incumbent. While open-seat candidates may not have clear knowledge about their opposition’s policy stances, the availability of information about a candidate’s personal characteristics is less dependent on incumbency. Thus, the difference in negativity early in a campaign is driven mostly by a lack of policy negativity, not personal negativity.

Figure 3 – Negative Issue Content

Note: Trends are smoothed using a Lowess smoothing algorithm

Figure 4 – Negative Personal Content

Note: Trends are smoothed using a Lowess smoothing algorithm

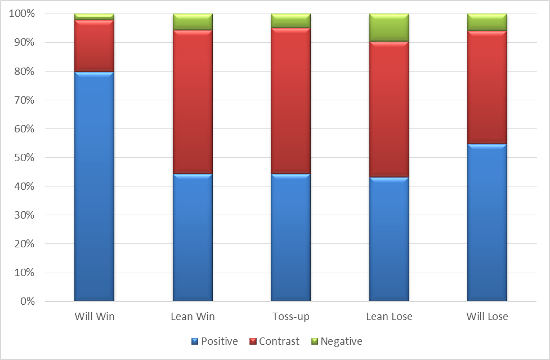

In terms of predicting negative rhetorical strategy, however, we find that competitiveness remains the best predictor of campaign negativity. Previous scholars have found that negative rhetoric encourages information-seeking behavior and thus favors little-known challengers. Engaging in negative campaigning also involves additional risks, and thus, incumbents are more likely to forego negative rhetoric. Campaigns are more likely to go negative if they are not sure winners, seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5 – Campaign Rhetoric by Likelihood of Electoral Victory

Sure losers are actually more likely to go positive than candidates who are either ahead or behind in a fairly close race. In races that are competitive, there is little difference in campaign tone between candidates who are ahead and those behind. The timing of the use of this vitriol, however, depends in part on whether there is an incumbent in the race and whether political stances of the candidates are well established.

This article is based on the paper ‘When to Attack: The Trajectory of Congressional Campaign Negativity’, in American Politics Research.

Featured image credit: Joe The Goat Farmer (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of U.S.App– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1UpNN2Q

_________________________________

Hans J.G. Hassell – Cornell College

Hans J.G. Hassell – Cornell College

Hans J.G. Hassell is an Assistant Professor of Politics at Cornell College. His research focuses on political parties, elections and political behavior, and Congress. He is interested in how the actions of parties and political elites affect the decisions of individuals to become involved in the political process. His work has appeared in the American Journal of Political Science, the Journal of Politics, and Political Behavior.

Kelly R. Oeltjenbruns – Washington University Law School in St. Louis

Kelly R. Oeltjenbruns – Washington University Law School in St. Louis

Kelly R. Oeltjenbruns is a JD candidate at Washington University Law School in St. Louis. A recent graduate of Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa, with a degree in Politics, Oeltjenbruns’ research focuses on campaign strategy and rhetoric.