US Citizens have a right to vote in federal elections in their former states even if they have permanently left the country. Brian Kalt argues that this right, and the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act from which it flows, has constitutional problems given that those who have left are no longer ‘people of the state’. He writes that Congress cannot simply rewrite states’ voter-eligibility requirements as it pleases. He suggests that to address the problem, Congress could establish territory-style representation in the form of non-voting House delegates or piggyback reforms on to the proposed National Popular Vote Interstate Compact.

US Citizens have a right to vote in federal elections in their former states even if they have permanently left the country. Brian Kalt argues that this right, and the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act from which it flows, has constitutional problems given that those who have left are no longer ‘people of the state’. He writes that Congress cannot simply rewrite states’ voter-eligibility requirements as it pleases. He suggests that to address the problem, Congress could establish territory-style representation in the form of non-voting House delegates or piggyback reforms on to the proposed National Popular Vote Interstate Compact.

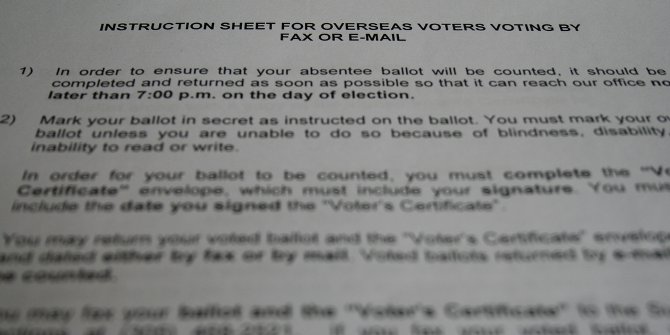

Eligible voters who have left the U.S. permanently can vote in federal elections as though they still live at their last stateside address. They need not be residents of their former states, or be eligible to vote in state and local elections, or pay any state or local taxes. The Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA), enacted in 1986, forces their former states to let them vote for President, Senate, and House this way.

This is unconstitutional and should be changed. I am sympathetic to my fellow citizens who have given up their stateside residences but prize their voting rights; I argue that Congress can best address these constitutional problems by expanding voting rights rather than reducing them.

UOCAVA has many constitutional deficiencies. Voting for Congress is supposed to be a matter not just of citizenship but of place, but UOCAVA sprinkles millions of voters into states and districts that are no longer their places.

The Constitution states that federal representatives are supposed to be chosen by “the people of the several states,” and senators from each state by “the people thereof.” But people who have left the country permanently are not “people of the state” where they vote. The Constitution also specifies that people who vote for federal representatives and senators must be qualified to vote for their state’s house of representatives. UOCAVA ignores this requirement too.

As for presidential elections, states choose for themselves how to cast their electoral votes. Congress cannot simply rewrite states’ voter-eligibility requirements as it pleases. Of course, there are constitutional provisions that hem in the states here—they cannot deny the vote on the basis of sex, or race, and other such things. But denying the vote on grounds that someone no longer lives in the state violates no such provisions.

When Congress debated the Overseas Citizens Voting Rights Act (OCRVA) in the 1970s—UOCAVA’s predecessor, which first set things up this way—it thought it could act because of its power to protect citizens’ rights to vote and to live where they pleased. Despite constitutional objections from some members and from the Department of Justice, the law’s proponents felt that these rights trumped any technicalities. (That view did not carry the day; instead, there was a general sense that members should just pass the law and leave consideration of the Constitution to the courts. It is forty years later, though, and no court has spoken on the issue.)

Credit: Ido Mor (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

The rights to vote and to live where one pleases are certainly important. Congress has a general power, under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment, to vindicate rights like these. Indeed, just before OCVRA’s enactment, the Supreme Court approved voting legislation that protected federal voting rights for people who moved interstate just before an election. But by applying overseas, and forever, OCVRA went too far. For OCVRA to come under Congress’s Section 5 power it would have to be a Fourteenth Amendment violation for states to preclude former residents from voting—and it isn’t.

One stark contrast makes this clear. If my rights as a U.S. citizen to vote in federal elections and to live where I please are so sacrosanct, why do my fellow citizens who live in Washington, D.C. not have a right to vote for Congress? Why do U.S. citizens in Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, and the U.S. Virgin Islands have no right to vote for Congress or for President?

It is odd that I would retain my federal voting rights if I emigrated to North Korea but would lose them if I moved to D.C. or a U.S. territory. But courts have ruled consistently that it is constitutional to deprive the latter citizens—who are not “people of a state”—of any vote for Congress or President. Since that is constitutional, then it would be constitutional for my state to stop letting me vote here if I emigrated to another country. And since that is constitutional, Congress has no power to force my state to do otherwise.

There was one other Section 5 justification for OCVRA: equal protection. Before OCVRA, most states—encouraged by earlier federal laws—chose to allow overseas military personnel, federal employees, and their dependents to vote at their stateside addresses. They typically did not extend this courtesy to private expatriates, though, and OCVRA prevented the states from continuing such disparate treatment. But while Congress had the power to prevent such disparate treatment, it lacked the power to do so this radically. States can be forced to be even-handed to absentee voters without being forced to treat permanent expatriates as quasi-citizens for life.

What to do? One legislative solution would be to let permanent expatriates vote, just in the right place. Permanent expatriates do have an interest in federal law and policy (particularly given the unusual way that the U.S. taxes its expatriates), but their interests are geographically distinct. As such, Congress could establish representation for permanent expatriates similar to that enjoyed by residents of the territories: dedicated, non-voting delegates in the House. By concentrating permanent expatriates’ votes this way, their interests would be represented more directly than by spreading them thinly over 435 districts where more local concerns are (appropriately) given higher priority. More importantly, this kind of representation would not be unconstitutional.

Unfortunately, losing voting representation in the House and all representation in the Senate and the Electoral College would be a step back for permanent expatriates’ voting rights. It would make permanent expatriates no worse off than U.S. citizens who live in the territories. Still, finding a way to preserve permanent expatriates’ voting rights, especially for President, is a worthy goal and an essential one if there is to be any real chance of Congress taking action.

One possibility would piggyback on the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC), a clever suggestion for switching to a national popular vote that has recently gained momentum. The NPVIC leverages the states’ ability to decide how to allocate their own electoral votes; member states agree to award their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote, but only when enough states to constitute a majority of the Electoral College have signed on. If the NPVIC passes, or if Congress gets in front of it and passes a constitutional amendment to institute a national popular vote for President, it would present a perfect opportunity to discuss the proper scope of who gets included in the national popular vote. It would be an optimal time, in other words, to give proper presidential voting rights to permanent expatriates and citizens living in the territories.

UOCAVA is unconstitutional but entrenched, because so many people—understandably—care more about citizens getting to vote than they do about constitutional niceties. But there is no reason that voting rights for permanent expatriates needs to come at such a price. Permanent expatriates can be enfranchised without disrespecting the Constitution.

This article is based on the paper ‘Unconstitutional But Entrenched: Putting UOCAVA and Voting Rights for Permanent Expatriates on a Sound Constitutional Footing’, in the Brooklyn Law Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1JfJdQV

_________________________________

Brian Kalt – Michigan State University

Brian Kalt – Michigan State University

Brian Kalt is Professor of Law & the Harold Norris Faculty Scholar at Michigan State University. Before coming to MSU College of Law, Professor Kalt worked at the Washington D.C. office of Sidley and Austin in one of the top appellate law practices in the country. He has also served as a law clerk for the Honorable Danny J. Boggs, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit. Professor Kalt’s research focuses on structural constitutional law and juries.

Even as I have worsened a likely ulcer by reading this, I am grateful. Not only grateful, but this article, along with additional information, namely, that total number of U.S. citizens living abroad, and through the Acts named, actually have more delegates than many U.S. states. How very interesting, too, that it was a UK website that first appeared in my search, even as this fine article was written by U.S.-based Mr. Kalt.

Subsequent to reading this, immediate contact was made with U.S. Legislators, for all the good it will do.

PS Gratitude, too, for having a system that did not delete my comment even though I had an error and had to backspace.