Metropolitan areas in the US often contain many local governments, which can work collaboratively or against each other’s interests. Rebecca Hendrick and Yu Shi create a number of indices to measure this local government fragmentation in metropolitan areas. These include indices of how population is sorted on educational racial, income and poverty lines, local government fiscal responsibility, and the impact of sales tax revenues on local government finances. They find that the population index of fragmentation is correlated with population sorting and segregation along social and demographic lines.

Metropolitan areas in the US often contain many local governments, which can work collaboratively or against each other’s interests. Rebecca Hendrick and Yu Shi create a number of indices to measure this local government fragmentation in metropolitan areas. These include indices of how population is sorted on educational racial, income and poverty lines, local government fiscal responsibility, and the impact of sales tax revenues on local government finances. They find that the population index of fragmentation is correlated with population sorting and segregation along social and demographic lines.

Local governments can interact competitively, which can affect their land use and taxation decisions in ways that harm the entire region. They can also collaborate to provide services and reduce common threats, and they can conflict with each other directly such as through lawsuits. We look at how to measure this fragmentation and related characteristics of local governments in metropolitan regions that economists and political scientists recognize as affecting how governments interact. In our research, we develop several indices of local government fragmentation and related characteristics that have been measured for the largest 51 metropolitan regions in the US. We show that there is significant variation in these characteristics across the regions, which may yield clues about how local governments interact and whether these interactions are beneficial or costly for individual governments and the region as a whole.

Although scholars, practitioners, and politicians agree that fragmentation is important, they disagree greatly about whether it and some forms of interaction, such as competition, are good or a bad for governments and metropolitan regions. Does fragmentation promote competition and hinder collaboration? Does competition between local governments promote efficiency as in private markets, or does it create sprawl through uncontrolled growth and economic development? Is it possible for local governments in a highly fragmented region to resolve shared problems through voluntary interactions, or must there be a strong central authority to coordinate their actions and enforce mutually beneficial behavior from all? While our research does not answer these questions, the indices we develop can be correlated with other regional characteristics that are important to the debate about the effects of fragmentation.

Generally speaking, metropolitan regions that are fragmented have many small, local jurisdictions that are distinct and operate independently of each other and with respect to a central governing body. When defined as the number of local jurisdictions, fragmentation of a region can be measured simply by counting the number of local governments. The problem with this measure is that larger regions will always be more fragmented than smaller regions, so it might make more sense to measure fragmentation as the number of local governments per capita or per square mile. Fragmentation can also be defined as the degree to which local governments in a region overlap, or the degree to which the region is dominated by the central city or one form of local government. Alternatively, fragmentation can be defined in terms of the fiscal responsibility of local governments in a region rather than the number of local governments. Using this approach, we create another fragmentation index that combines the proportion of spending by different local governments, types of local governments, and overlapping governments to determine the extent to which responsibility for services is dispersed among many or few governments.

In addition to the two indices of fragmentation, one based on population and the other based on fiscal responsibility, we also created three further indices:

- One which measures the degree to which population within the 51 regions is sorted into Census designated places on education, race, income, poverty, and percent Hispanic.

- One that measures the degree to which fiscal responsibility is decentralized from state to local government, since the fiscal responsibility of local governments in the US varies greatly by state government.

- An index which shows the prevalence of sales in the revenue stream of local governments in the regions, which also varies primarily by state.

Both of the latter two characteristics- fiscal decentralization and importance of sales taxes- have been linked by scholars to behaviors that affect interaction of local governments.

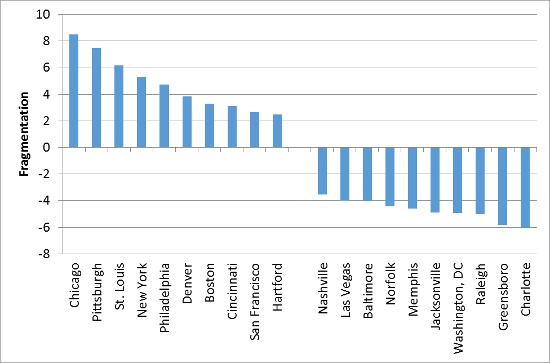

Figure 1 below shows the combined fragmentation values on the population-based index for the top 10 and bottom 10 metropolitan regions in the US. These values show the sum of the Z-scores for all six component measures of this index. The table shows what many scholars know, which is that metropolitan regions in the Northeast and Midwest are more fragmented and regions in the South and West tend to be less fragmented. Looking across the five indices shows that the Chicago, St. Louis, and Denver regions are similarly situated all of them. They are more fragmented, their populations are more highly sorted, they are more fiscally decentralized with respect to state-local relations, and they are more driven by sales taxes. On the other end of the indices, Norfolk, Greensboro, Charlotte, and Baltimore are less fragmented, have lower population sorting, are more fiscally centralized, and are less driven by sales taxes.

Figure 1 – Fragmentation of top and bottom ten metropolitan regions

We also find that the population based index of fragmentation is positively correlated with population sorting. This finding supports the logical conclusion of claims made by the well-known economist Charles Tiebout – that populations will be more segregated on social and demographic characteristics across local government, especially at the municipal level, in regions that are highly fragmented. Tiebout argued that competition between governments would promote efficiency and that fragmentation would allow populations to sort themselves into local governments that provide the services they desire at tax levels they are willing to pay. Such sorting, however, is likely to result in numerous local governments within a region in which the population is poor and immobile, which is not desirable for the citizens of these governments or the region as a whole.

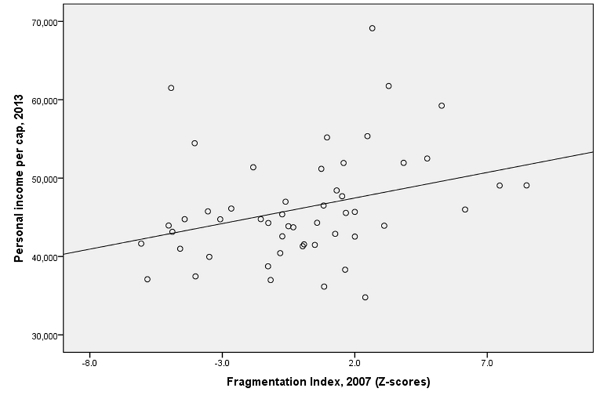

Earlier this year, Richard Florida reported on our research in a CityLab article. He showed how the population-based fragmentation index correlated with other regional characteristics such as population density, vote for Obama in 2012, share of commuters who take public transportation to work, and the concentration of high-tech industries. Figure 2 below shows how this index correlated with income per capita in 2013, which suggests that local government fragmentation does not appear to harm metropolitan regions as Florida notes. Although fragmented regions may be better off economically, they are more segregated, as demonstrated by the correlation between the population sorting index and average wages, and have higher income inequality.

Figure 2 – Correlation of fragmentation index with income per capita across 51 metropolitan areas

This article is based on the paper, ‘Macro-Level Determinants of Local Government Interaction: How Metropolitan Regions in the United States Compare’, in Urban Affairs Review.

Featured image credit: Caroline (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1Lhyi6i

______________________

Rebecca Hendrick – University of Illinois at Chicago

Rebecca Hendrick – University of Illinois at Chicago

Rebecca Hendrick is a professor in the Department of Public Administration at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her current research focuses on financial management of local governments and fiscal interactions (competition and collaboration) between local governments at a regional level, particularly in the Chicago metropolitan region. Her work appears in public administration, political science, and urban affairs journals.

Yu Shi – University of Illinois at Chicago

Yu Shi – University of Illinois at Chicago

Yu Shi is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Public Administration at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her research focuses on intergovernmental relations, collective actions, and public debt management. She is currently working on her dissertation, which explores the impact of fiscal federalism on government performance in the United States.