Every year more than half a million prisoners are released back into the community in the US, presenting an array of challenges for those reentering society. In new research which tracks prisoners released from Massachusetts state prisons, Jaclyn Davis and Catherine Sirois find that a large majority of releasees called on their families for support such as money, accommodation and childcare. They also find that many released prisoners experience housing insecurity and difficulties in finding paid employment.

Every year more than half a million prisoners are released back into the community in the US, presenting an array of challenges for those reentering society. In new research which tracks prisoners released from Massachusetts state prisons, Jaclyn Davis and Catherine Sirois find that a large majority of releasees called on their families for support such as money, accommodation and childcare. They also find that many released prisoners experience housing insecurity and difficulties in finding paid employment.

In 2013, Ray, a 59-year-old black man, was released from a Massachusetts prison, after completing a 15-year sentence. He almost immediately experienced difficulties in reconnecting with the community. Ray spent his first week out of prison bargain shopping alone throughout Boston until an anxiety attack in a department store overwhelmed him with feelings that he did not belong. At close to one month out, Ray was making an effort to spend more time with the residents at the sober house where he was living, but after becoming accustomed to isolation, he said that his attempts at socializing felt like homework.

Maria meanwhile, a white woman in her late twenties, frequently forgot to eat breakfast or lunch for several months after her release from prison because she was used to being called to her meals.

As Ray and Maria demonstrate, the process of social integration after prison release presents an array of challenges for men and women reentering society. However, few accounts of this process exist, as prison releasees are often weakly attached to stable households, unevenly involved in mainstream social roles, and sometimes on the run, making them an elusive population for research.

In new research, we analyze the critical period immediately after prison release using new data from the Boston Reentry Study (BRS), a panel survey of 122 men and women, including Ray and Maria, leaving Massachusetts state prisons for neighborhoods in the Boston area. An examination of this data reveals that material insecurity combined with the adjustment to social life outside prison creates a stress of transition that burdens social relationships in high-incarceration communities.

Family Support

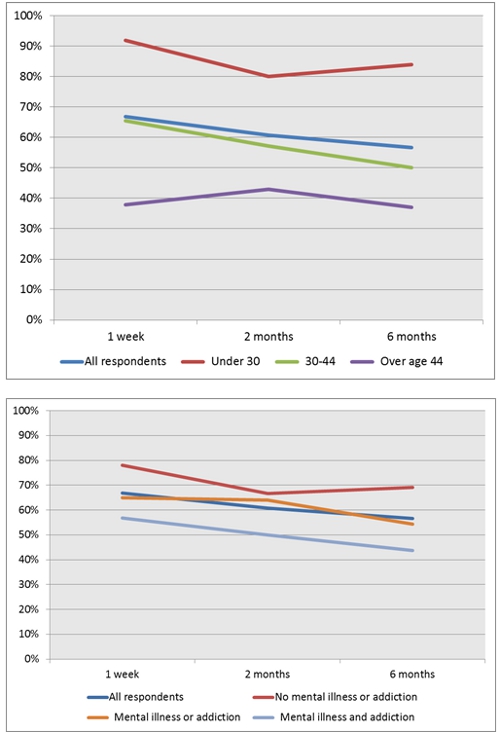

Families often helped with readjustment after prison by celebrating the end of incarceration and providing support to a population adjusting to the everyday complexity of free society. As Figure 1 illustrates, about two-thirds of respondents received either financial support from family or were staying with a family member in the first week after release. Most of this support came from female relatives such as mothers or sisters. Family financial support declined through the first six months of community return as respondents gained greater financial independence. Families also provided critical support in other areas such as childcare and transportation, and were more likely to provide financial support than partners.

Figure 1 – Percentage of respondents living with family or receiving money from family after prison release

Older respondents and those reporting drug problems and mental illness were more persistently detached from family. Forty percent of those over 44 and about one-third of those with mental illness and addiction never reported family support at any of the three postrelease interviews. Women were much more likely to receive money or housing from family than were men.

Housing

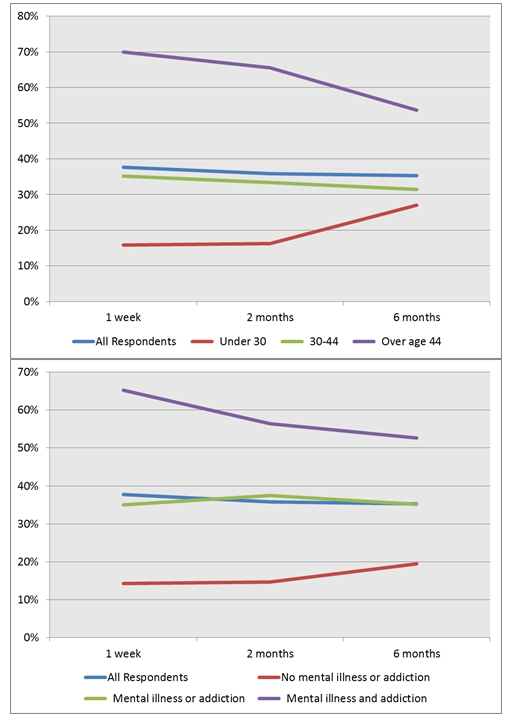

Housing instability was an enduring issue for respondents leaving prison. Through six months after incarceration, about two-thirds of respondents stayed with family or friends. The remainder slept in marginal or temporary housing that consisted mostly of shelters and sober houses. Figure 2 shows the high levels of housing insecurity among those over age 44 and those with histories of addiction and mental illness. More than half of both groups remained in marginal or temporary housing through six months after release.

Figure 2 – Percentage of respondents in marginal or temporary housing after prison release

There were also many instances of unstable housing that are not fully captured in our quantitative results. For example, living with family members was not counted as temporary or marginal, although in some cases relatives themselves were unstably housed or were made so by the arrival of a family member newly released from prison. Taking in family members after prison release can add to already crowded households and sometimes violate leases, risking eviction. Although living with family is relatively stable compared to shelters and other temporary housing, around 20 percent of respondents who were staying with family at one week after release reported a new address two months later.

Public Assistance and Employment

Public assistance was a key source of support after prison release. The percentage of respondents receiving public assistance rose from just over 40 percent at one week to over 70 percent at two months, and remained at this level over the next few months. Almost all respondents who received public benefits were enrolled in the Supplement Nutrition Assistance Program (food stamps), and almost all respondents were enrolled in Massachusetts extended Medicaid program prior to their release. Benefit receipt tended to be higher among those with weaker family support, more unstable housing, or among those who were older and with histories of addiction and mental illness.

Figure 3 – Percentage of respondents in paid employment after prison release

We observed persistently low employment rates among women and those with histories of mental illness and addiction (see Figure 3). Overall trends in employment were similar to those for public assistance, climbing significantly from 18 to 43 percent in the first two months and then remaining at a relatively high level. However, qualitative data showed that steady fulltime work was rare. Respondents who continued work-release jobs (which began in prison) or who had family connections to work were the most stably employed. More commonly, respondents were initially employed in day labor often doing construction, home improvement, and, in the winter, snow removal.

Adjusting and Coping after Prison

While the stress of the transition is demonstrated across the sample, older respondents and those with histories of addiction and mental illness experienced the most severe hardship. About half of respondents age 45 and older described some form of anxiety during their first week out.

Despite reports of stress and hardship in the transition from prison to community, nearly all respondents described the joys and happiness of prison release. When asked, “What’s the best part about being out?” the responses “freedom” and “family” were the most common. Still, our analysis shows that most returning citizens leave incarceration for poverty in which they are largely reliant on family support, housing is often insecure, and incomes are supplemented by government programs. Frequent cases of anxiety and detachment for those returning to society from prison added stress to families and communities already severely impacted by high rates of incarceration. Alongside the joys of leaving prison, many of the basic conditions for community membership proved highly elusive to those reentering society.

Further information on the Boston Reentry Study can be found here. This article is based on the paper, ‘Stress and Hardship after Prison,’ authored by Bruce Western, Anthony Braga, Jaclyn Davis, and Catherine Sirois in the American Journal of Sociology.

Featured image credit: ajari (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1g9KRIb

_________________________________

Jaclyn Davis – Harvard University

Jaclyn Davis – Harvard University

Jaclyn Davis is a Research Assistant with the Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management (PCJ) at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS). She is currently managing the New York Reentry Study, directed by Bruce Western, a research project interviewing men and their families in New York City throughout their first year after release from incarceration.

Catherine Sirois – Harvard University

Catherine Sirois – Harvard University

Catherine Sirois managed the Boston Reentry Study, directed by Bruce Western, Anthony Braga, and Rhiana Kohl, a longitudinal survey of 122 men and women recently released from Massachusetts state prison. She is currently a doctoral student in Sociology at Stanford University.

1 Comments