In new research Daniel Byrd, Deborah Hall, Nicole Roberts and José Soto seek to understand whether liberal and moderate Whites are biased towards Black politicians over White politicians, and if this favorability is mitigated by any implicit racial bias. They find that liberal and moderate Whites do have a preference for Black politicians over White politicians on a variety of measures of political support. They also find that this favorability disappeared among those who were more likely to rate Black politicians as less intelligent because of their implicit pro-White/anti-Black biases

In new research Daniel Byrd, Deborah Hall, Nicole Roberts and José Soto seek to understand whether liberal and moderate Whites are biased towards Black politicians over White politicians, and if this favorability is mitigated by any implicit racial bias. They find that liberal and moderate Whites do have a preference for Black politicians over White politicians on a variety of measures of political support. They also find that this favorability disappeared among those who were more likely to rate Black politicians as less intelligent because of their implicit pro-White/anti-Black biases

Politically non-conservative (liberal and moderate) Whites tend to hold egalitarian views of society and are less likely than conservative Whites to discriminate against Blacks in situations where race is apparent. In fact, research suggests that non-conservative Whites often discriminate in favor of Blacks relative to Whites in situations where race is apparent. Despite showing overt favoritism toward Blacks, non-conservatives growing up in the U.S. may nevertheless hold unconscious or implicit biases against Blacks as a result of the negative and pervasive messages explicitly or implicitly passed down from one generation to the next. Stereotypes rooted in the belief that Blacks are biologically inferior, such as the idea that Blacks are inherently less intelligent than Whites may be particularly powerful. Accordingly, non-conservative Whites may discriminate against Blacks in situations where their conscious ability to override their biases is limited.

While previous research has shown how racial biases affect the political attitudes of White conservative populations, less is known about how racial biases affect the political attitudes of non-conservative Whites. In new research, we sought to understand if politically non-conservative Whites discriminated in favor of Black politicians relative to White politician across four domains of political support (i.e., voting for a politician, donating money to a politician, having confidence in the ability of a politician to be an effective lawmaker and assessing the intelligence level of a politician) and if implicit racial biases mitigated that bias. We predicted that liberal and moderate Whites would show greater preferences for Black politicians relative to White politicians on these measures of political support. At the same time, because non-conservative Whites may also harbor negative feelings towards Blacks on a subconscious level, we predicted that implicit racial bias would eliminate the favorability bias for ratings of intelligence, in particular, because intelligence taps into historical forms of racism.

To test these predictions, we recruited 671 politically non-conservative Whites (439 females and 232 males, with an average age of 32 years) via the Project Implicit website to participate in a study about political preferences. Project Implicit attracts a wide range of people who are interested in learning more about research or understanding more about their unconscious attitudes. While broader than a traditional college student sample, samples drawn from the Project Implicit website should not be considered representative of the general population. In our study, liberal and moderate Whites were randomly assigned to view a photograph of either a Black or a White politician and read a speech implied to have been given by the politician. After reading the speech, participants were asked to rate the likelihood that they would vote for or donate money to the politician, how confident they felt about the politician’s ability to effectively advocate a position, and how intelligent they believed the politician was.

To avoid the possibility that the results of our study could be attributed to any one politician or any one political issue, participants were assigned to one of twelve conditions in which they could view one of six pictures of Black politicians or one of six pictures of White politicians. We also used six different speeches, two each from three different political issues (voter identification, healthcare, or minimum wage) to avoid the possibility that our results could be attributed to a specific policy issue. Lastly, participants were asked to take the race Implicit Association Test (IAT). The race IAT is a computer based test which measures how fast respondents associate faces of Black and White people with evaluative attributes or categories (i.e., positive words, such as ‘‘winner,’’ or negative words, such as ‘’loser’’). Faster judgments made when people are asked to associate White faces with positive words than Black faces with positive words would indicate that a respondent has a pro-White bias on the IAT.

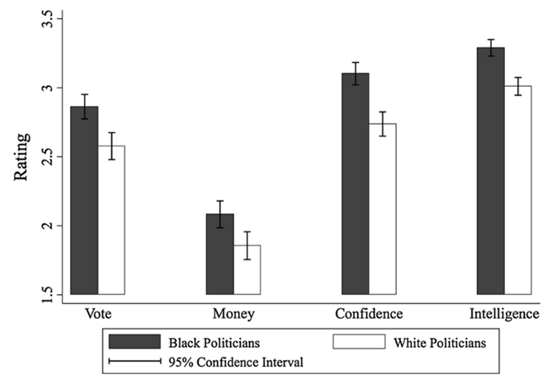

As predicted, participants showed a bias in favor of Black politicians relative to White politicians on all four measures of political support (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Ratings of politician on dependent measures

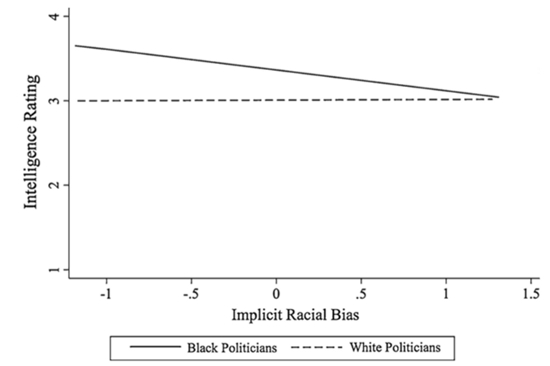

Implicit racial biases were not found to mitigate the favorability bias for the voting, money or confidence dependent variables. However, for the intelligence ratings, those with greater anti-Black/pro-White implicit racial biases rated Black politicians as less intelligent than those without the implicit bias, effectively eliminating the favorability bias (see Figure 2). Intelligence ratings of White politicians were uncorrelated with implicit bias. We note that even those high in implicit bias did not rate Black politicians’ intelligence as lower than that of Whites, but that ratings were relatively lower, and that this effect was not present for the other three measures of political support.

Figure 2 – Implicit racial bias as a predictor of perceived intelligence of politician

Note: Positive numbers indicate a stronger pro-White/anti-Black bias

Our findings paint a “glass half full” picture on the issue of race in American politics. On one hand, the greater preferences shown for Black politicians relative to White politicians might suggest that non-conservative Whites show a genuine preference for Black politicians, and/or are trying to bend over backwards to compensate for past injustices. On the other hand, Whites may still experience discomfort regarding how they should perceive Blacks. Further, as implicit racial biases effectively eliminated this favorability bias for the one measure that taps into old-fashioned forms of racism (i.e., intelligence), our research suggests that even amongst White populations that show preferences for Blacks explicitly, implicit biases may ultimately undermine support for Black politicians.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Do Politically Non-conservative Whites ‘‘Bend Over Backwards’’ to Show Preferences for Black Politicians?’, in Race and Social Problems.

Featured image credit: Light Brigading, Flickr BY-NC-2.0

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1izYqSW

_________________________________

Daniel Byrd

Daniel Byrd

Daniel Byrd holds a bachelor’s degree in psychology from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and a doctoral degree in social psychology from the University of Washington. Daniel has produced original research on race relations in America which was featured in many prominent news outlets including Huffington Post, The Nation, CNN and Salon. Daniel currently lives in Los Angeles and works in public policy.

Deborah Hall – Arizona State University

Deborah Hall – Arizona State University

Deborah Hall is an Assistant Professor in the School of Social & Behavioral Sciences at Arizona State University. She earned her doctoral degree in social psychology from Duke University. She is the director of the Identity & Intergroup Relations Lab, which conducts research aimed at understanding how membership in social groups shapes individuals’ perceptions, behavioral choices, and interactions with others, and the New College Statistics and Methods (SAM) Lab.

Nicole A. Roberts – Arizona State University.

Nicole A. Roberts – Arizona State University.

Nicole Roberts is an Associate Professor of psychology in the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Arizona State University. She earned her doctoral degree in clinical psychology from the University of California, Berkeley, and completed her clinical internship and post-doctoral training at the Northern California Veterans Administration Health Care System and University of California, Davis Department of Psychiatry. She is the director of the Emotion, Culture, and Psychophysiology Laboratory and studies how cultural and biological forces intersect to shape emotion and emotion regulation. Her research has been published in outlets such as Family Process, Psychophysiology, and Emotion.

José Soto – Pennsylvania State University

José Soto – Pennsylvania State University

Jose is an Associate Professor in the Clinical Science Program at the Pennsylvania State University. He received his Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley in 2004 and completed his internship and postdoctoral training at UCSF/San Francisco General Hospital. His research examines the intersections of culture, health, and emotion, with an emphasis on the study of ethnic minority culture and those experiences associated with ethnic minority status (e.g., discrimination, oppression). He is the 2012 recipient of the Charles and Shirley Thomas Award from division 45 for his contributions to the education and training of students of color as well as his professional presence within ethnic minority communities.