Recent scandals in the US government such as the Veterans Health Administration scandal point to the need to reexamine how much autonomy and discretion public servants are able to exercise. In new research which examines the ethical behavior of public servants, Edmund C. Stazyk finds that highly trained managers view organizational problems through a compliance based, legalistic lens and one which is based on their own personal moral compass. He argues that by providing public servants with more educational opportunities, they may be more likely to use this ‘fusion’ approach to ethical decision making.

Recent scandals in the US government such as the Veterans Health Administration scandal point to the need to reexamine how much autonomy and discretion public servants are able to exercise. In new research which examines the ethical behavior of public servants, Edmund C. Stazyk finds that highly trained managers view organizational problems through a compliance based, legalistic lens and one which is based on their own personal moral compass. He argues that by providing public servants with more educational opportunities, they may be more likely to use this ‘fusion’ approach to ethical decision making.

Hardly a year passes without a major scandal rocking government somewhere, with many scandals seeming to originate from the intentional and unintentional ethical lapses and missteps of public servants. The US has certainly experienced its fair share of ethical scandals lately. A short list of notable transgressions limited to the federal government would surely include 1) Veteran’s Health Administration officials lying about how long veterans waited for healthcare, 2) the General Service Administration’s misuse of federal dollars to host extravagant conferences and award employees excessive bonuses, and 3) the Internal Revenue Service’s targeting of Tea Party and Patriot groups for greater administrative scrutiny.

It’s no surprise such ethical scandals are typically followed by a clarion call from citizens, watchdog groups, and savvy politicians to “hold the rascals accountable.” Each of these parties assume—or at least assert—the reason public administrators so frequently behave in ways contrary to the logic of good governance is because we’ve allowed them too much discretion and autonomy. Consequently, heads must roll, runaway bureaucracies have to be reined in, and stronger ethics legislation should be crafted to prevent future transgressions.

What’s striking about this claim is that it’s hardly new. Scholars and practitioners interested in government and governance have grappled with this same fundamental issue for at least the last 200 years. Yes, it’s a thorny matter—how much discretion and autonomy should administrators have? In the US context, Wilson’s 1887 politics-administration dichotomy, the Friederich–Finer debates of the early 1940s, and even many modern administrative movements such as new public management with its emphasis on accountability and performance measurement demonstrate how important questions of discretion and autonomy are to our beliefs about “good governance.”

Nevertheless, any effort to determine how much discretion and autonomy is appropriate requires we also consider those factors that shape how public employees come to understand their obligations and responsibilities to civil society. Fortunately, ethicists have long grappled with this issue.

US ethics research and practice have often paralleled the Friedrich-Finer debate. Finer argued that the autonomy afforded US public administrators was too great and the misuse of power was a near certainty in the absence of strict political oversight and tight legislative control. Conversely, Friedrich believed that public servants’ internal sense of professionalism guided them toward responsible action; thus, in his opinion, public administrators should be granted greater autonomy.

Ethicists have applied these ideas to describe two competing interpretations of, and approaches to, administrative ethics. On one hand rest compliance-based (or low road) ethics systems that are grounded on the logic of external control—often legal in nature. On the other hand are those approaches rooted in personal responsibility stemming from an individual’s internal moral compass (or high road ethic).

Most important, for this discussion, is the moral distinction between low and high road ethics. Low road approaches start from the assertion that we must monitor and rely on external checks to limit bureaucratic discretion. High road approaches assume most public servants intuitively know and opt to do what is “right”, making external checks unnecessary and degrading.

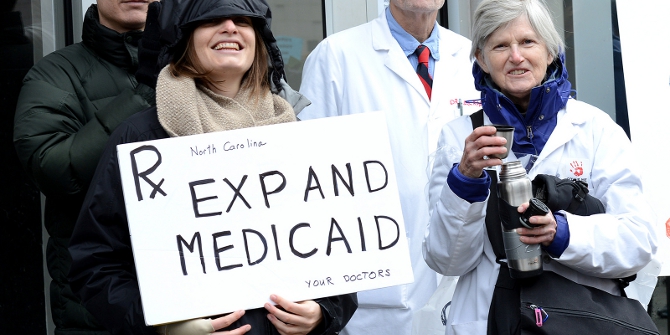

Credit: Dan Mason (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Echoing Friedrich and the logic of high road ethics, a closely related stream of research on public service motivation (PSM) argues public employees frequently try to do what is right. Yet, little research has examined whether PSM is related to ethical behavior or how PSM influences the behavior of public employees—particularly when confronting ethical dilemmas. To begin addressing this shortcoming, Randall Davis of Southern Illinois University and I recently examined three questions:

1) Do senior managers in US local governments who believe their department attaches significant importance to various public values also report higher levels of PSM?

2) In such cases, do public employees confronting ethical dilemmas express a preference for making decisions that comport with a high road approach to ethics?

3) Do public employees’ decision-making preferences differ between whites and minorities, men and women, and on the basis of one’s organizational tenure and formal academic training?

What we learned offers new and important insights into our understanding of public servants ethical decision-making processes. Our most significant finding was that education matters. Employees who had less formal education were more likely prefer high road decision-making when confronting ethical dilemmas whereas highly educated employees were just as likely to apply high and low road approaches.

There are at least two reasons why this finding is intriguing. First, echoing arguments from PSM scholarship, we expected the application of high road decision-making approaches would be more pronounced among highly-educated employees due to their professional training. This was not the case. Second, given this finding, it appears education plays a prominent role in shaping the moral and intellectual behavior and standards of public administrators.

It is especially striking that our results indicate highly trained senior managers with strong PSM often view organizational problems through a fusion of high and low road approaches. In many ways, this may be a positive—albeit unanticipated—finding. We should not always assume internally grounded ethics are superior to compliance-based systems. Laws often reflect prevailing social norms and expectations. As such, “good” public servants may be those who account both for prevailing social norms as well as their own internally based understanding of right and wrong when confronting difficult ethical dilemmas.

If, alternatively, less-educated senior managers prefer making decisions that comport solely with their own personal PSM (ignoring laws), there may be some cause for concern. These employees may exercise their discretion and autonomy in ways that run contrary to the broader public interest. The good news is a simple solution exists: provide additional educational opportunities, especially ethics training, to workers in the hope that it causes employees to view ethical dilemmas using a fusion approach.

Two caveats are worth mentioning. First, since this is the first such study on this topic, additional research is necessary before we know whether current findings are generalizable. Also, we were unable using our data to determine whether more or less formal education actually translates into better [ethical] outcomes for citizens and society.

Despite any limitations, our findings shed new insight into an enduring set of questions and challenges confronting public administration: How much discretion and autonomy should administrators have? What factors shape public employees’ understanding of their responsibilities and obligations? What is the relationship between the exercise of administrative discretion and the ethical behavior of public employees? Most importantly, our results suggest further, more nuanced consideration is necessary on the part of scholars and practitioners.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Taking the ‘high road’: does public service motivation alter ethical decision making processes?’, in Public Administration.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1MAiHlP

_________________________________

Edmund Stazyk – University at Albany (SUNY)

Edmund Stazyk – University at Albany (SUNY)

Edmund Stazyk is an assistant professor in the Department of Public Administration and Policy, housed within the Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy at the University at Albany (SUNY). Professor Stazyk specializes in organization theory and behavior, public administration theory, public management, and human resource management. He studies a wide range of topics related to organizational performance and employee motivation.