The ongoing segregation of Blacks who live in many of America’s cities has not only economic, but political consequences as well. In new research, Jessica Trounstine finds that not only are the most segregated cities more likely to see racially polarized voting, they also spend less on services for their residents. She writes that her results mean that compared to whites, nonwhites are much more likely to live in communities that are unable to provide adequate public services for their residents.

The ongoing segregation of Blacks who live in many of America’s cities has not only economic, but political consequences as well. In new research, Jessica Trounstine finds that not only are the most segregated cities more likely to see racially polarized voting, they also spend less on services for their residents. She writes that her results mean that compared to whites, nonwhites are much more likely to live in communities that are unable to provide adequate public services for their residents.

Many of the negative social and economic consequences of segregation have been well-documented – Blacks who live in segregated metro areas have lower levels of education, higher rates of poverty, and a higher likelihood of single-parenthood than Blacks who live in more integrated places. But, segregation also has political consequences. Although neighborhood racial segregation has lessened in recent decades, today the typical white American lives in a neighborhood that is about 75 percent white, while Black, Latino, and Asian Americans live in substantially more integrated places. These patterns have created stark divides between white and non-white communities. When a city is residentially segregated by race, issues cleave along racial and not just spatial lines and groups are more likely to be intolerant, resentful, and competitive with each other. The result is that segregated cities have a high degree of racial political conflict. Segregated cities, less able to build consensus, also have lower levels of spending on a wide range of public goods – from streets, to sewers, to assistance for the poor.

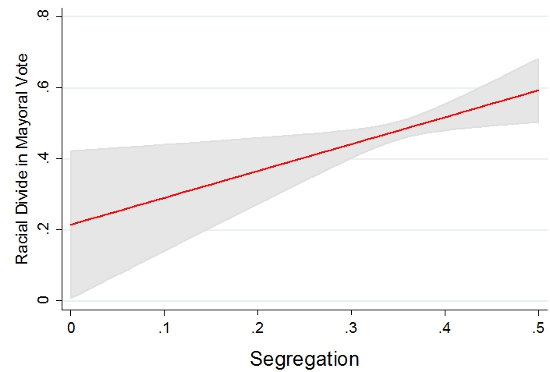

In an analysis of mayoral election contests in the 25 largest cities in America, I find that more segregated cities are more likely to witness racially polarized voting. As Figure 1 shows, in segregated cities whites and people of color are vastly more likely to support different candidates for mayor than whites and people of color in more integrated places.

Figure 1 – Segregation and racial divide in mayoral vote

Note: Predicted marginal effects of regressing racial divide in mayoral vote on segregation with controls for city demographics and governmental institutions. Racial divide in mayoral vote measured as the absolute value of the largest difference in racial group support for winning candidate. Segregation measured using Theil’s H index calculated for two groups (whites and non-whites). Gray shading represents 95% confidence interval.

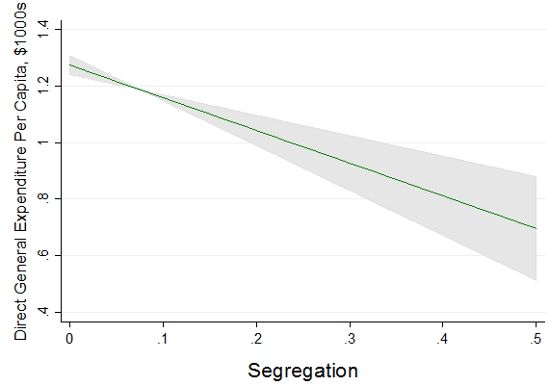

Figure 2 shows that segregated cities also spend less on services for their residents. They raise fewer dollars, and have smaller budgets for roads, law enforcement, parks, sewers, welfare, housing, and community development.

Figure 2 – Segregation and expenditure per capita

Note: Figure shows predicted relationship between Theil’s H segregation index and direct general expenditure per capita in constant 2007 dollars. Gray shading represents 95% confidence interval.

Compared to a city in the 25th percentile of segregation (like Palm Bay, Florida, Oregon City, Oregon, or San Louis Obispo, California) a city in the 75th percentile (like Madison, Wisconsin, Scranton, Pennsylvania, or Jersey City, New Jersey) will spend about $100 less per resident each year. Given that the average per capita expenditure on police is about $180, and about $61 on parks, this difference has the potential to dramatically affect the quality of public goods that individuals experience.

It is important to note that these results hold regardless of the size of the minority population (which generally tends to be supportive of spending on city services). As segregation increases – whether the minority population is very small, or a majority of city residents – spending declines. Nearly 3/4ths of minority residents live in cities that are extremely segregated. In the aggregate these results mean that compared to whites, nonwhites are much more likely to live in communities that struggle to generate adequate public goods for their residents. As the nation has become more diverse, it has also become more unequal.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Segregation and Inequality in Public Goods’ in the American Journal of Political Science.

Featured image credit: Dean Chahim (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1TgtXWY

_________________________________

Jessica Trounstine- University of California, Merced

Jessica Trounstine- University of California, Merced

Jessica Trounstine is an Associate Professor in the School of Social Sciences, Humanities and Arts at the University of California, Merced. She studies American politics with a focus on sub-national politics, primarily concentrating on large cities. Her work studies the process and quality of representation. She is particularly interested in how political institutions enhance or limit the ability of residents to achieve responsive government.

Average white person lives in a neighborhood that is 75% white. That sounds very high to me.

Sorry I meant very low.

America looks more and more like apartheid South Africa. You only need to hear what Donald Trump is saying to understand. It was easier to change the constitution to give minorities equal rights; changing the white psyche is a another matter entirely.Racism may be here to stay.

hi,

can I please ask for sources of figure 2?

thank you