Marijuana has now been legal in Colorado for medicinal use for more than 15 years. Over this time, authorities in neighboring Nebraska (where the drug remains illegal) have become concerned about the potential spillover of marijuana into their state’s counties. In new research, Jared M. Ellison and Ryan E. Spohn find that Nebraska’s border counties, and to a lesser extent those along the I-80 highway corridor, have experienced an upward trend in marijuana-related arrests and jail admissions. In light of these findings, they write, both states and the federal government may need to rethink their marijuana laws and make decisions about penalties and potential legalization.

Marijuana has now been legal in Colorado for medicinal use for more than 15 years. Over this time, authorities in neighboring Nebraska (where the drug remains illegal) have become concerned about the potential spillover of marijuana into their state’s counties. In new research, Jared M. Ellison and Ryan E. Spohn find that Nebraska’s border counties, and to a lesser extent those along the I-80 highway corridor, have experienced an upward trend in marijuana-related arrests and jail admissions. In light of these findings, they write, both states and the federal government may need to rethink their marijuana laws and make decisions about penalties and potential legalization.

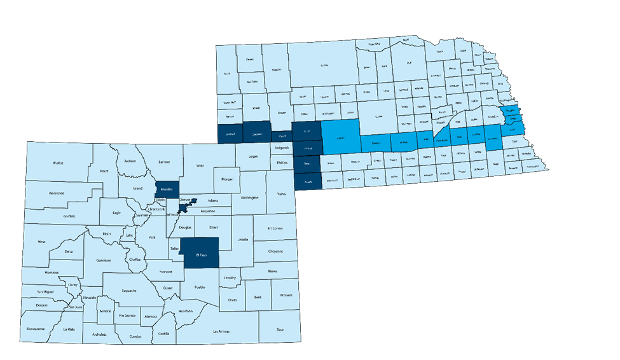

In 2000, Colorado became one of the first states to legalize medical marijuana. It was not until 2008 and 2009, however, that the number of medicinal users began to rapidly expand. Soon after this expansion, criminal justice officials across the state of Nebraska suggested that there had been an influx of marijuana into their counties, and more specifically, in the counties along the Colorado-Nebraska border and those along Interstate 80 (i.e., a major transportation route running through the state). In response to the purported increases, the Nebraska state legislature passed Legislative Resolution 520, which commissioned a special committee to discuss possible solutions to the issue (e.g., increased state law enforcement presence and/or state funding). In the interest of providing senators with an accurate description of the problem, we compared the rates of marijuana-related possession arrests, sale arrests, jail admissions, and associated costs of incarceration in two groups of so called “treatment counties”—the 7 counties along the Colorado border and the 11 counties along the I-80 corridor (see Figure 1)—to comparable rates in the remaining 75 counties in the state of Nebraska from 2000 through 2013.

Figure 1 – Maps of Colorado and Nebraska with neighboring counties and I-80 corridor

Notes: Figure courtesy of iStockphoto LP. Permission granted under the iStock content license agreement. Highlighted Colorado counties (i.e., Boulder, Denver, and El Paso) were identified as the most common “source” of Colorado-born marijuana seizures in other states.

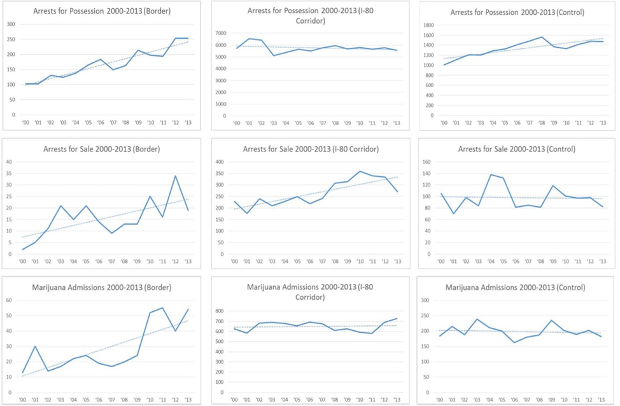

A preliminary examination of raw counts suggested that border counties had experienced the most noticeable upward trend in marijuana-related arrests and jail admissions over the 14-year period (Figure 2). While there was also a notable increase in sale arrests in I-80 counties and an increase in possession arrests in control counties, the number of sale arrests and jail admissions actually fell in control counties. However, given that raw trends in arrests and jail admissions are susceptible to population changes as well as law enforcement activity, we compared rates of marijuana-related criminal justice activity from 2000 to 2004 with respective rates from 2009 to 2013, after controlling for state and local law enforcement activity.

Figure 2 – Trends in Marijuana-related Possession, Sale, and Jail Admissions

The results of our regression analyses showed that while border counties had comparable rates of marijuana arrests and jail admissions initially (i.e., 2000-2004), they were significantly higher than control counties from 2009 to 2013. The one exception to this trend was that border counties and those along the I-80 corridor had higher rates of possession arrests both before and after the influx of medical marijuana registrants in Colorado. Counties along the I-80 corridor had higher rates of possession arrests from 2009 to 2013, but we found no evidence to suggest that these counties experienced higher relative rates of sale arrests or jail admissions from 2009 to 2013. Moreover, despite higher rates of marijuana-related arrests and jail admissions, a supplemental analysis of costs for incarceration showed that only I-80 counties had higher average costs during both time periods compared to control counties. This suggests that marijuana offenders are not detained long enough to make a fiscal impact on the rural jails that operate near the border; I-80 county jails, on the other hand, have more bed space and greater monetary resources than border counties, which provides them with the ability to incarcerate marijuana offenders and keep them for longer periods of time.

With regard to whether the rates changed significantly, we found that only border counties experienced a significant and positive change in the rate of possession arrests, sale arrests, and jail admissions. In other words, Nebraskan border counties were the only counties to experience a significant increase in the rate of marijuana-related criminal justice activity after the expansion of medical marijuana in Colorado. In line with claims made by criminal justice officials in Nebraska then, it is at least plausible to suggest that the increasing availability of medical marijuana, or reductions in risk associated with its use in Colorado, have contributed to an increased prevalence of illegal marijuana in Nebraska.

Most importantly, we found that these trends persist despite controls for population changes and levels of local and state law enforcement. The results clearly indicated that the activity of the Nebraska State Patrol is perhaps the more influential of the two law enforcement controls, as counties with higher proportions of arrests made by the state patrol typically had higher rates of marijuana-related arrests and jail admissions. The presence of local law enforcement, however, had very little to do with the rate of marijuana arrests, and only influenced the rate of marijuana-related jail admissions from 2009 to 2013.

Our results have considerable policy implications for states located near others that legalize marijuana, although it remains far too early to estimate the most recent changes that may result from recreational legalization. The obvious implication is that states such as Nebraska, as well as the federal government, may need to ultimately rethink their marijuana laws, and make decisions regarding penalty enhancements, reductions, and/or forms of legalization. The Attorneys General of Nebraska and Oklahoma, for example, have brought a joint lawsuit in federal court against Colorado (States of Nebraska and Oklahoma v. Colorado, 2014), alleging that under the US Constitution’s Supremacy Clause, Colorado’s legalization of marijuana is unconstitutional. Colorado’s Attorney General has since filed a counterclaim, joined by the Attorneys General of Washington and Oregon, contending that while marijuana is illegal under federal law, the Drug Enforcement Administration and the US Attorney’s office have decided to take a hands-off approach to the retail regulation of marijuana; thus, any lawsuit should be directed at the federal government for their lack of enforcement rather than at the states whose citizens have voted to legalize the drug. As of this writing, however, the US Supreme Court has yet to decide whether it will hear the case. Moreover, the Obama administration recently (December 16, 2015) asked the Court to avoid the lawsuit, and suggested that the Court should only step in when states themselves are at odds, rather than when third parties violate federal and state law in another state.

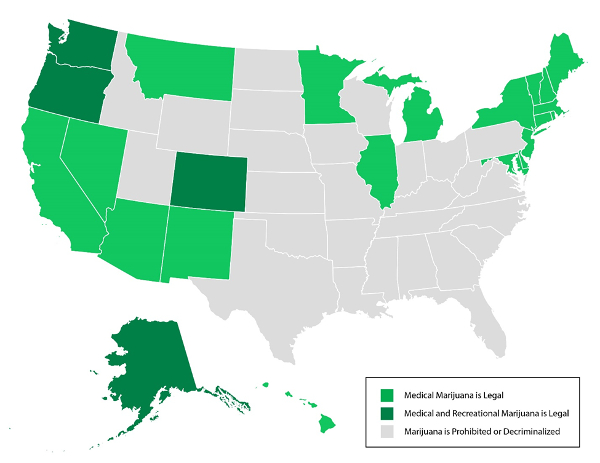

Figure 3 – Legalization of Marijuana in the United States (As of March, 2015)

Notes: Figure courtesy of iStockphoto LP. Permission granted under the iStock content license agreement.

In any event, the legalization of marijuana—both for medicinal and recreational purposes—is sure to create a lasting debate throughout the United States in the coming years. A recent public opinion poll shows that a majority of Americans now support legalization, and twenty-three states and the District of Columbia (D.C.) have existing or planned medical marijuana programs as of March, 2015 (Figure 2). Moreover, four states—Alaska, Colorado, Washington, and Oregon—as well as Washington, D.C., have legalized recreational marijuana. While recent evidence suggests that these policy changes may have a number of economic benefits for these states (e.g., cost savings and state revenue), our analysis shows that the greater availability, public promotion, and cultural adaptation to these changes may have spillover effects on the illegal marijuana market across state lines. In the interest of informing the looming debate, then, researchers should continue to explore how and why varying degrees of legalization in one state might impact the amount of illegal marijuana across the border.

This article is based on the paper, “Borders up in smoke: Marijuana enforcement in Nebraska after Colorado’s Legalization of Medicinal Marijuana” in Criminal Justice Policy Review.

Featured image credit: Kent Kanouse (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1QYnAde

_________________________________

Jared M. Ellison – University of Nebraska Omaha

Jared M. Ellison – University of Nebraska Omaha

Jared M. Ellison is a doctoral candidate in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of Nebraska Omaha. His research interests include short-term incarceration, the criminal court system, and offender reentry. Jared has published in several scholarly journals, including Criminal Justice and Behavior, The Prison Journal, Journal of Criminal Justice, and Trauma, Violence, and Abuse.

Ryan E. Spohn – University of Nebraska Omaha

Ryan E. Spohn – University of Nebraska Omaha

Ryan E. Spohn is director of the newly established Nebraska Center for Justice Research at the University of Nebraska-Omaha, where he routinely performs statewide and local research and evaluation activities targeted at improving the performance of Nebraska’s juvenile justice, criminal justice, and corrections activities. Dr. Spohn has published in numerous victimization, sociology, and criminal justice scholarly journals, including the Violence Against Women, Criminal Justice Review, Social Forces, and Victims and Offenders.

It could also be that there has been an increase in enforcement efforts along I-80. From the beginning law enforcement complained that legal marijuana in a neighboring state, medical and otherwise, would result in more marijuana coming into the state. It stands to reason that they would start looking for more pot in vehicles on the roads in border areas and along I-80. More is probably coming from Colorado. That doesn’t mean marijuana is more availabe though. It means more of the existing demand is being supplied by product originating in Colorado than before when more was coming from other sources. There hasn’t been a shortage of pot anywhere in the country really since the mod Seventies. It’s easy to get everywhere. There are many sources everywhere. All legalization does is change the source from which the product is obtained. Most people who want to smoke it are already doing so, legal or not. People in Nebraska were already smoking pot. Now more may be coming from a state where it is legal, but that means less comes from Mexican cartels and other organized crime groups. It’s not a bad thing.

Yes.

Big John you are rightly said, It’s easy to get everywhere. There are many sources everywhere. All legalization does is change the source from which the product is obtained. Most people who want to smoke it are already doing so, legal or not. People in Nebraska were already smoking pot. Now more may be coming from a state where it is legal, but that means less comes from Mexican cartels and other organized crime groups. It’s not a bad thing.