Approval for interracial marriages in US society has increased drastically in the past 25 years, and Asians are at the forefront of this trend; one third of Asian marriages in the US are interracial. Jennifer Lee writes that because of the selectivity of Asian immigrants towards the highly educated, Asians as a group have gone from being denied basic rights such as citizenship and the right to marry, to being perceived as desirable marriage partners. She argues that this shift should not be mistaken for true equality with White Americans; Asian Americans are racialized as a ‘model minority’, and the shift towards their perception as ‘marriageable’ only covers Asian women – reflecting how this group is exoticised and stereotyped in gender-traditional ways.

Approval for interracial marriages in US society has increased drastically in the past 25 years, and Asians are at the forefront of this trend; one third of Asian marriages in the US are interracial. Jennifer Lee writes that because of the selectivity of Asian immigrants towards the highly educated, Asians as a group have gone from being denied basic rights such as citizenship and the right to marry, to being perceived as desirable marriage partners. She argues that this shift should not be mistaken for true equality with White Americans; Asian Americans are racialized as a ‘model minority’, and the shift towards their perception as ‘marriageable’ only covers Asian women – reflecting how this group is exoticised and stereotyped in gender-traditional ways.

The Rise of Intermarriage

Interracial marriage is on the rise, and accounts for 1 in 12 marriages in the United States. As Figure 1 shows, among recent marriages, the ratio narrows to 1 in seven. That intermarriage was illegal in sixteen states as late as 1967 make these figures remarkable.

Figure 1- Intermarriage Trends, 1980-2010

Note: New marriages numbers are from 1980 Census and 2008-2010 American Community Survey (ACS). All marriages are from the US Decennial Census data and 2008-2010 ACS, IPUMS. Source: Pew Research Centre

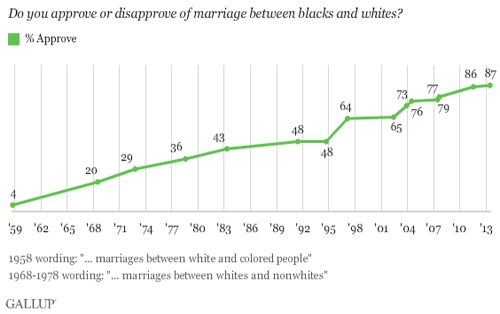

The increase in intermarriage has gone hand-in-hand with Americans’ growing support for it; today, as Figure 2 illustrates, 87 percent of Americans approve of intermarriage, up from only one-quarter in 1970 when only 1 percent of marriages crossed racial lines. Among young Americans ages 18-25, the support for interracial marriage is near universal at 97 percent.

Figure 2 – Approval of Interracial Marriage 1959-2013

Among US groups, Asians are at the vanguard of this trend; close to one-third of Asian marriages in the United States are interracial marriages, and these figures are even higher for US-born Asians. But this has not always been the case. Less than a century ago, Asians were dubbed “marginal members of the human race,” full of “filth and disease,” and “unassimilable” by the country’s Anglo Saxon communities.

Figures 3 and 4 – Representations of US Chinese in 19th and early 20th century American popular culture

Consequently, they were denied the rights of US citizenship, denied the right to intermarry, residentially confined to ethnic enclaves, barred from attending White schools, and, in the case of Japanese Americans, interned during World War II. It was not until the passage of the McCarren-Walter Immigration and Naturalization Act in 1952 that Asians were finally extended the right to become naturalized US citizens. Yet despite decades of institutional exclusion, discrimination, and racial prejudice, Asian Americans now exhibit the highest rates of intermarriage.

So how have Asian Americans gone from unassimilable to marriageable in less than a century? The answer lies in the changing selectivity of Asian immigrants to the United States, which, in turn, changed their perceived suitability as marriage partners. This change is the result of the passage of the landmark Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which ushered in a new stream of highly selected, highly educated immigrants from Asia.

The Hyper-Selectivity of Asian Immigration

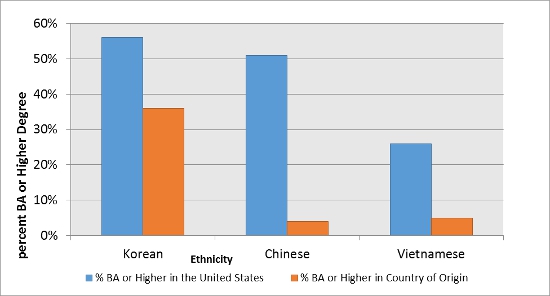

To illustrate the meaning of selectivity, let’s look at the three largest East Asian immigrant groups in the United States—Chinese, Vietnamese, and Koreans. We find that each is highly selected from their country of origin. More than half (56 percent) of Korean immigrants in the United States has a Bachelor’s Degree or higher compared to only 36 percent of adults in Korea, meaning that US Korean immigrants are more than one and a half times as likely to have graduated from college than their ethnic counterparts who did not immigrate.

The degree of selectivity among Vietnamese immigrants is even higher than that of Koreans in the United States. More than one quarter (26 percent) of Vietnamese immigrants has at least a Bachelor’s Degree, but the comparable figure among adults in Vietnam is only 5 percent. Chinese immigrants are the most highly selected: 51 percent has graduated from college compared to only 4 percent of adults in China, meaning that US Chinese immigrants are more than twelve times as likely to have graduated from college than Chinese adults who did not immigrate.

Figure 5 – Educational achievement by ethnicity

In addition, some Asian immigrant groups—like Chinese and Koreans—are not only highly selected compared to their non-migrant counterparts, but they are also more highly educated than the general US population, 28 percent of whom have graduated from college. This dual positive immigrant selectivity is what Min Zhou and I refer to as “hyper-selectivity.”

The change in the selectivity of contemporary Asian immigrants affects the patterns incorporation, including residential segregation. The Pew Research Center shows Asian Americans are the least segregated among US minority groups. Only 11 percent of Asian Americans live in a majority Asian census tracks compared to 43 percent of Hispanics and 41 percent of Blacks. That Asian Americans experience less residential segregation than Hispanics and Blacks means that they have more opportunity to come into contact with members of other groups, especially non-Hispanic Whites. Increased intergroup contact, in turn, affords more possibilities to form interracial friendships, partnerships, and marriages.

The Social Construction of “Marriageability”

While intergroup contact is a necessary condition for intermarriage, it is not a sufficient one. What is also necessary is the willingness of members of different groups to cross group boundaries to date and marry. Legal scholar Rachel Moran made this point by stating that intermarriage occurs within “culturally accepted parameters.” In The Diversity Paradox, Frank D. Bean and I extended Moran’s argument by underscoring that intermarriage with Asians is more “culturally acceptable” for Whites than intermarriage with Blacks because group boundaries have historically been more flexible for US immigrant groups than for native-born Blacks. This is even more so when immigrants are hyper-selected, as is the case for many contemporary East Asian immigrant groups.

Marriageability—like attractiveness and desirability—is what social scientists refer to as “socially constructed.” Its definition is historically specific, changes with context, and is relational. Asian Americans are the perfect example of this; once deemed unfit for US citizenship, filthy, and unassimilable, they have become America’s most marriageable minority group. This lesson underscores the point that who one finds attractive and chooses to date and marry—which many believe is strictly an individual and personal choice—is socially constructed, and the result of opportunities and constraints.

In addition, the social construction of “marriageable” is not only socially constructed by race but also by gender. Asian women intermarry at twice the rate of Asian men, and studies of on-line dating preferences reveal that while Asian women are highly preferred among males across racial groups, Asian men are the least preferred of all men among women. Researchers posit that the imbalance results from the gendered racialization of Asian Americans, which feminizes Asianness in such a way that Asian women are stereotyped as exotic, hyper-sexual, and gender-traditional, and therefore, “desirable.” By contrast, Asian men are stereotyped as unmasculine by Western ideals, and, consequently, “undesirable.”

That the gendered patterns of intermarriage occur in opposing directions for Blacks (with Black males intermarrying at twice the rate of Black females) reveals that gender and racial status do not operate equally for all groups, once again underscoring the social construction of “marriageability.”

Racial Mobility and Incorporation

While Asian Americans have experienced racial mobility and show higher levels of education and median household incomes than White Americans, it would be a mistake to conclude that they have reached equal status with Whites. While Asian Americans, on average, evince high socioeconomic outcomes, including intermarriage, they continue to be racialized as the “model minority” who has achieved success “the right way”—a divisive trope that pits them against other minority groups, especially Blacks and Latinos. Furthermore, they experience a unique form of gendered racialization that feminizes Asianness in a way that stereotypes Asian women as exotic and gender-traditional, and Asian men, as unmasculine. The continued gendered racialization of Asian Americans reveals that despite their socioeconomic incorporation and rising intermarriage, racial mobility does not mean full incorporation.

This article is based on the paper, “From Undesirable to Marriageable: HyperSelectivity and the Racial Mobility of Asian Americans”, in The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science.

Featured image credit: A/PA Heritage Festival (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1OtwklI

_________________________________

Jennifer Lee – University of California, Irvine

Jennifer Lee – University of California, Irvine

Jennifer Lee is a Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Irvine. She is co-author of The Asian American Achievement Paradox (with Min Zhou, Russell Sage Foundation, 2015), in which they debunk the popular assumption that Asian American educational achievement can be reduced to cultural values and traits. Her new research focuses on Asian Americans and affirmative action. Follow her on Twitter @JLeeSoc.