Despite being seen by much of the world as a very religious country, religious affiliation in the US is in decline, with fewer Americans now likely to attend church. In new research, Andre P. Audette and Christopher L. Weaver write that some churches have attempted to address declining attendance by becoming more politically active in order to attract more people from the declining pool of the religious. Using survey data, they find that churches which engaged in more political activities tended to attract larger congregations, something they attribute to the greater likelihood that political partisans will ‘shop around’ when deciding which church to regularly attend. They warn that while such strategies may boost churches’ attendance in the short-term, the politicization of religion may turn more people off religion overall.

Despite being seen by much of the world as a very religious country, religious affiliation in the US is in decline, with fewer Americans now likely to attend church. In new research, Andre P. Audette and Christopher L. Weaver write that some churches have attempted to address declining attendance by becoming more politically active in order to attract more people from the declining pool of the religious. Using survey data, they find that churches which engaged in more political activities tended to attract larger congregations, something they attribute to the greater likelihood that political partisans will ‘shop around’ when deciding which church to regularly attend. They warn that while such strategies may boost churches’ attendance in the short-term, the politicization of religion may turn more people off religion overall.

Although the United States is still remarkably religious compared to other advanced industrial countries, it has become less so over the past few decades; around 23 percent of Americans now no longer claim any religious affiliation. Similarly, Americans are less likely to pray, attend church, and say religion is very important to their lives than they once were. As a result, many churches have been forced to close due to increasingly vacant pews.

Scholars have typically attributed this religious decline to the involvement of the Religious Right in American politics. As Christianity became more closely associated with conservatism and the Republican Party in the American public’s mind, many liberals and Democrats abandoned what they saw as a religion that no longer represented their political values. Indeed, nearly 40 percent of those who no longer attend church blame a difference of belief with the religion or religious leaders. In other words, churches’ political activities hurt religion by driving away dissenting adherents.

While this seems to explain why the US has become less religious overall, it is not clear that involvement in politics actually drives politically active churches’ own members away. Politics may hurt religion as a whole, but it does not necessarily hurt the political churches themselves. In fact, our research has found quite the opposite: politically active churches have actually grown over time. Politically active churches simultaneously shrink the size of the overall religious marketplace and help those churches recruit from the remaining adherents who want a role for religion in politics.

If this seems counterintuitive, consider an example from an entirely different kind of market. For the past several years, traditional fast food restaurants have been losing customers to more upscale, healthier alternatives. Rather than pursue these former customers by trying to offer healthier options, a number of fast food chains have instead focused on being more competitive among the remaining fast food consumers by adding even more decadent menu items like “mashup” foods (such as a certain pseudo-sandwich that substitutes two pieces of fried chicken for bread). These items do little to change the minds of customers who have abandoned fast food for being too unhealthy, but they do appeal to the people who still reliably consume fast food. Although the overall number of fast food consumers continues to shrink, the most successful chains can gain more of the remaining consumers by doubling down on the very practices that are shrinking the market.

Similarly, a church’s political activities may do little to change the public image of religion in the US, but they do make the church more appealing to those who still attend church. Powdersville First Baptist Church in Easley, South Carolina, exemplifies of this process. In what its pastor describes as a “Lazarus story,” it went from being nearly insolvent to a thriving church with active missionary activities around the world. This has been attributed to the efforts of Pastor Brad Atkins, who assumed the role of senior pastor at the church in 2006. Under his leadership, average attendance at Sunday worship services grew from around thirty to an average of 350 people in 2015. Atkins instituted a number of new programs and services to help resurrect the dying church, including a voter registration program with the goal of registering every eligible voter in his congregation. Atkins claims to “even lick the envelope and stick on the stamp for them.”

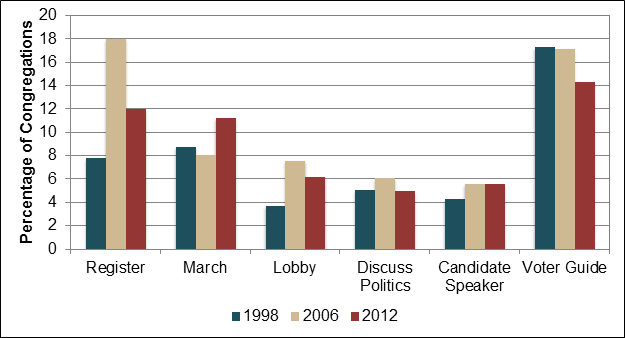

To demonstrate the effect that these types of political activities have on church growth, we analyze data from the National Congregations Study (NCS), which surveyed a nationally representative sample of American religious congregations in 1998, 2006, and 2012. The survey collected a range of information about these congregations, including the size of their membership and the activities within the church. A number of these activities are political: registering voters, attending a march or rally, lobbying elected officials, organizing groups to discuss politics, hosting a candidate for office as a speaker, and distributing voter guides. The prevalence of these activities in each time period is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 — Congregational Political Activities by Year

In all three years of the NCS survey, churches that engaged in more political activities tended to be significantly larger in size. This difference in size held even when accounting for the influence of other factors (e.g., denomination, location, etc.) that might affect a church’s size, including its other non-political activities. That is, political activity, more so than other types of activity, seems to drive up church membership.

In addition to surveying congregations in these three years, in 2006 the NCS recontacted a random sample of congregations that participated in the 1998 NCS, which allows us to examine changes between 1998 and 2006 for those congregations in the panel. Specifically, we examine the relationship between changes in political activity and congregational size over time. Beyond initial differences in size, we find that increasing the amount of political activity actually causes a church to gain members. Political churches tend to be larger to begin with, but churches that become more political grow even larger in size. What’s more, congregations with higher levels of political activity become larger over time, but congregations with more members do not become more political over time. Given this, we can be relatively confident that it is political activity that drives increased membership and not the other way around.

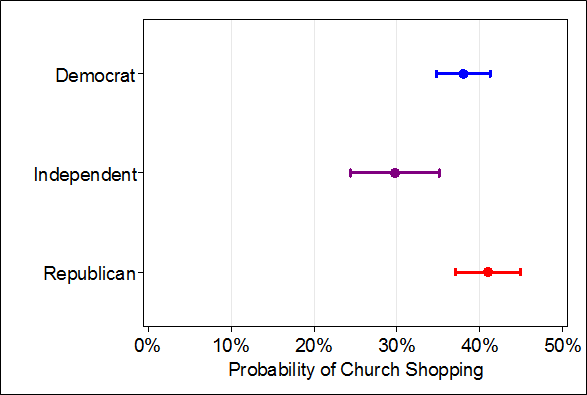

Furthermore, the NCS identified churches to sample by using the details provided by respondents to the General Social Survey (GSS). As such, at least one congregant from each of the NCS congregations filled out a survey for that year’s GSS. The 1998 GSS asked respondents whether they had ever shopped around for a church or visited different churches to compare and decide which to attend regularly. This allows us to examine the characteristics of church shoppers, who represent the most active religious consumers likely to be recruited by churches. As shown in Figure 2, even when accounting for other religious and socio-demographic factors, partisans are significantly more likely to church shop than independents. Since they already identify with a political organization, we might expect partisans to be the most likely to desire a politicized environment in church. This offers further evidence for our theory.

Figure 2 — Probability of Church Shopping by Partisanship

While politics can be good for churches, however, it may still be bad for religion. In fact, combining our findings with existing research on overall trends in religious attendance may present a grim outlook for the future of American religion. By pursuing an advantageous strategy in the short term and becoming more political, churches may further shrink the religious marketplace. Moreover, less political churches, such as Mainline Protestant congregations, have experienced the greatest losses in membership. While many of their members disaffiliate due to the politicization of religion nationally, others leave to attend churches that offer these very political activities. Ultimately, the market forces we describe may lead to an even starker divide between the religious and nonreligious than already exists in the United States.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Filling Pews and Voting Booths: The Role of Politicization in Congregational Growth’, in Political Research Quarterly.

Featured image credit: MTSOfan (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1RQQ47X

______________________

Andre P. Audette – University of Notre Dame

Andre P. Audette – University of Notre Dame

Andre Audette is a Ph.D. Candidate in American Politics and Constitutional Studies at the University of Notre Dame. His research focuses on political inequality and identity politics, and his dissertation work examines the role of churches in mobilizing or demobilizing Latinos for political action.

Christopher L. Weaver – University of Notre Dame

Christopher L. Weaver – University of Notre Dame

Christopher Weaver is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame. His research focuses on political behavior, public opinion, and identity politics.

Well written and valid. The Pastor John MacAurthur agreed with you in his sermon the Grace Church on Juy 18, 1993. He said, “You see, the church has one mission; we are a nation of priests. And a priest had one simple function, to bring people to God, to usher them into His presence. It is the only thing we are in the world to do. Frankly, if people die in a Communist government or a democracy, it really doesn’t matter if they end up in hell. If they die under a tyrant or a benevolent dictator, it doesn’t matter if they end up in hell. If they die believing that homosexuality is wrong or believing that homosexuality is right and end up in hell, it doesn’t matter. If they die as a policeman or a prostitute without Christ, they’re going to end up in the same place. Whether they die moral or immoral will make no difference in their eternity. Whether they stood on the side of the street with the pro-abortion rights group and screamed for legalizing and maintaining legal abortions, or on the other side of the street against abortion and screamed to stop the killing – if they didn’t know Christ they’re going to end up in the same place. Right? That isn’t the issue. The issue is salvation; the issue is salvation. And the sad reality is that when the church gets a moralizing, politicizing bent it usually has a negative impact on its evangelization mission, because then it makes the people hostile to the current system, and they become the enemies of the society rather than the compassionate friends.”

Here’s a link to that sermon: http://m.gty.org/Resources/Sermons/56-23