In the US, state Supreme Court judges are either appointed, elected, or more commonly, are subject to retention elections. Traditionally, electoral accountability boosts a court’s perceived legitimacy, but can this be undermined with the negative campaigning that can often come with elections? In new research, Benjamin Woodson examines this relationship, finding that the negative effects of campaigning can outweigh the positive boost provided through electoral accountability only in states with a large amount of campaign activity.

In the US, state Supreme Court judges are either appointed, elected, or more commonly, are subject to retention elections. Traditionally, electoral accountability boosts a court’s perceived legitimacy, but can this be undermined with the negative campaigning that can often come with elections? In new research, Benjamin Woodson examines this relationship, finding that the negative effects of campaigning can outweigh the positive boost provided through electoral accountability only in states with a large amount of campaign activity.

Elections are a political institution that are revered in theory and loathed in practice by the American public. The reverence stems from them providing the essential foundation of legitimacy for any democratic system. The loathing comes from the campaigning and political machinations surrounding elections.

This ambivalence applies to elections for executive or legislative positions but increases for elections to the judiciary, where many scholars (but not the majority of the American public) thinks it’s inappropriate for judges to be elected. One aspect of many scholars’ concern stems from the potential that elections and especially the campaigning that surrounds them may undermine the legitimacy of courts. My analysis of a survey administered by YouGov with a national sample of 819 respondents shows that these scholars are partially correct but do not take into account the multiple ways in which elections affect legitimacy perceptions.

The ambivalence Americans feel toward judicial elections causes them to have two opposing effects on the amount of legitimacy the American public attributes to state Supreme Courts. Since elections are the foundation of democratic legitimacy, they provide a boost to a court’s perceived legitimacy through electoral accountability, but this effect is counteracted by the negative influence on perceived legitimacy caused by campaign activities such as attack ads and campaign donations.

As a result, the overall effect of choosing judges through elections can be either positive or negative depending on the circumstances. In states where extensive campaigns by judges are rare, the positive effect caused by electoral accountability outweighs the negative effect caused by campaigning, and the system used to select judges in that state causes an overall increase in perceived legitimacy. In states where extensive judicial campaigns are common, the negative effect of campaigning is larger than the positive effect caused by electoral accountability, and the selection system causes an overall decrease in the perceived legitimacy of the judiciary.

Any study of judicial selection systems is complicated by the many idiosyncratic ways in which the American states choose judges for their state Supreme Courts. This diversity is usually simplified into four categories. In appointment systems some other public official chooses the judges. In partisan election states two or more candidates vie for one position and the largest vote total wins. Other states use non-partisan elections, which are similar to partisan elections except no party label appears on the voting ballot.

The fourth system called a retention election system or sometimes the merit system is the most common as well as the most complicated. In that system whenever a vacancy appears a judge is initially appointed to the position by some other public official. After a period of time, judges face a retention election in which voters are given the choice to retain them for a new term or remove them. No alternative candidate’s name appears on the ballot.

Usually, when scholars examine judicial selection systems they concentrate on these four traditional categories, but that leaves out variation in the norms influencing the amount of campaign activity in each state. In some states, judicial elections are rarely challenged and candidates engage in little to no campaign activity. In other states, elections are consistently challenged, campaigns spend substantial amounts of money and candidates attack each other.

I used a series of election activity indicators to differentiate between these two kinds of states. The first type of indicator counts the number of certain types of elections over the five election cycles prior to the survey being administered in the spring of 2013 (generally 2002-2012). These include counts of the total number of elections in a state, the number of challenged elections, the number of competitive elections and the number of open-seat elections. The second type uses campaign donations, and the indicator is based on the amount donated to all judicial candidates over the same time period. The third uses the public’s response to an item on the survey asking whether the subjects think their state Supreme Court is elected or appointed. The indicator is the percentage of people within each state who say the court is elected.

My conclusions are based on an examination of the relationship between these election activity indicators and the standard measure of perceived legitimacy for courts. This perceived legitimacy measure assesses whether people want to make fundamental changes to how the institution operates. I ran six separate models – one for each election activity indicator – with the measure of perceived legitimacy as the dependent variable, the election activity indicator as the main independent variable and a variety of control variables.

Four out of the six election activity indicators had a negative effect on perceived legitimacy. Only the total number of elections and the amount of campaign funding did not significantly affect perceived legitimacy. However, this is not completely surprising since many judicial elections involve no campaign activity, and the campaign funding variable did not include outside spending, which can sometimes be larger than the amount spent by the actual candidates.

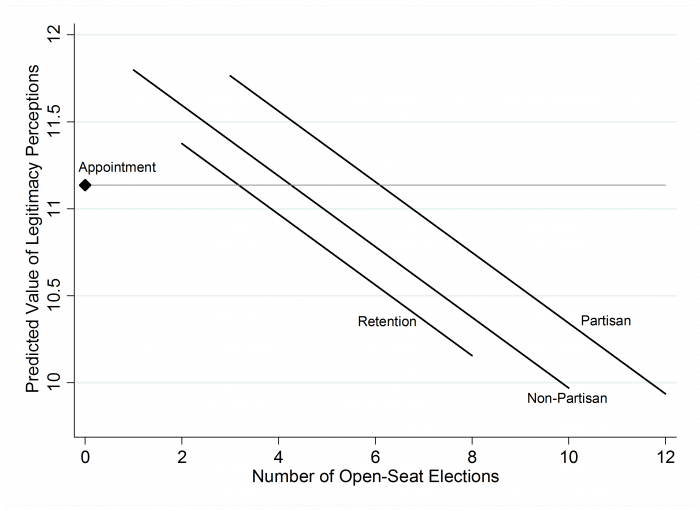

The number of open-seat elections indicator had the strongest effect on perceived legitimacy, and its results can be used to illustrate the substantive effects of election activity. Figure 1 shows the predicted level of perceived legitimacy, holding all other variables at their means, for all four of the traditional categories of judicial selection system across the number of open-seat elections. The figure shows that at low levels of election activity the amount of perceived legitimacy of all three types of elected courts is higher than that for appointed courts. At high levels of election activity, the level of perceived legitimacy is lower for all three types of elected courts compared to appointed courts.

Figure 1 – Election Activity and Legitimacy Perceptions

The predicted level of legitimacy is shown from the observed minimum of the open-seat election variable within each category to the observed maximum within that category. Since all appointment states have 0 open seat elections, it appears as a diamond. A thin line extends from that dot to ease comparison with the elected courts.

Further statistical analysis reveals that the difference between elected courts high in election activity and appointed courts is statistically significant, as is the difference between elected courts low on election activity and appointed courts.

These results make two important points. First, elections can but usually will not undermine the legitimacy of state Supreme Courts. Only in states with extremely high levels of election activity do the negative effects of campaigning outweigh the positive boost provided through electoral accountability. The negative effects are not overwhelming though. Even at the highest point of election activity the difference between an elected and appointed court is only 7 percent of the legitimacy measure’s total range, and the predicted level of legitimacy is above the index’s midpoint.

Second, when examining judicial selection systems it is important to take into account more than just the institutions written into law. Norms governing the amount of campaigning can be just as important. The election activity indicators categorize judicial selections systems not as lawyers and judicial scholars perceive them but on how they are experienced by the public, which is essential when examining the relationship between public opinion and judicial selection method.

This article is based on the paper, ‘The Two Opposing Effects of Judicial Elections on Legitimacy Perceptions’, in State Politics & Policy Quarterly.

Featured image credit: Phil Roeder (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2bLY5vk

_________________________________

Benjamin Woodson – University of Missouri – Kansas City

Benjamin Woodson – University of Missouri – Kansas City

Benjamin Woodson is an assistant professor of political science at the University of Missouri – Kansas City. His research interests involve the relationship between public opinion and judicial institutions. His most recent articles examine the effect that court decisions have on the legitimacy of courts and how those decisions affect public opinion on specific political issues.