Across the Unites States, the number of children taken into foster care every year varies greatly. In new research, Frank Edwards take a close look at how this number is influenced by states’ criminal justice, welfare, and child protection regimes. He finds that states with more punitive criminal justice systems are likely to put 4.9 children per 1,000 into foster care annually. States with generous welfare programs, on the other hand, are likely to put only 3.7 per 1,000 into foster care every year.

Across the Unites States, the number of children taken into foster care every year varies greatly. In new research, Frank Edwards take a close look at how this number is influenced by states’ criminal justice, welfare, and child protection regimes. He finds that states with more punitive criminal justice systems are likely to put 4.9 children per 1,000 into foster care annually. States with generous welfare programs, on the other hand, are likely to put only 3.7 per 1,000 into foster care every year.

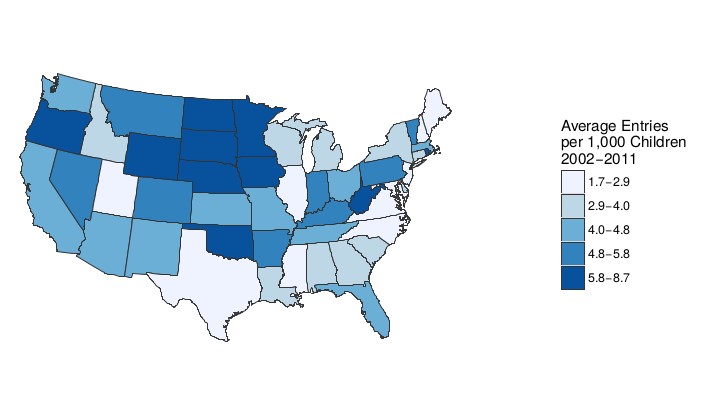

More than one in twenty children US children can expect to be separated from their families and enter foster care by the time the turn eighteen, and more than 400,000 children are currently in foster care. The number of children in foster care varies dramatically across states, and is poorly explained by risk-factors known to predict child abuse and neglect.

Figure 1 – Children taken in to foster care by state, 2002-2011

Note: Data from Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System and American Community Survey 2002 – 2011

The number of children entering foster care is driven not solely by child abuse and neglect, but by states’ varying politics and approaches to social problems. States with more punitive criminal justice systems tend to remove children from their homes far more frequently than those with generous and inclusive welfare systems. Two states with similar rates of child abuse and neglect, but different packages of social policies, are likely to have very different rates of foster care entry.

How policy regimes affect efforts at child welfare

Child welfare agencies are tasked with protecting children from abuse and neglect and frequently offer critical services to protect children. However, the experience of foster care is inherently disruptive, and frequently traumatic. Despite the critical role child protection plays in regulating family life, we know relatively little about why some states place children into foster care dramatically more than do others, or why the kinds of care children receive in foster care vary based on the place a child lives.

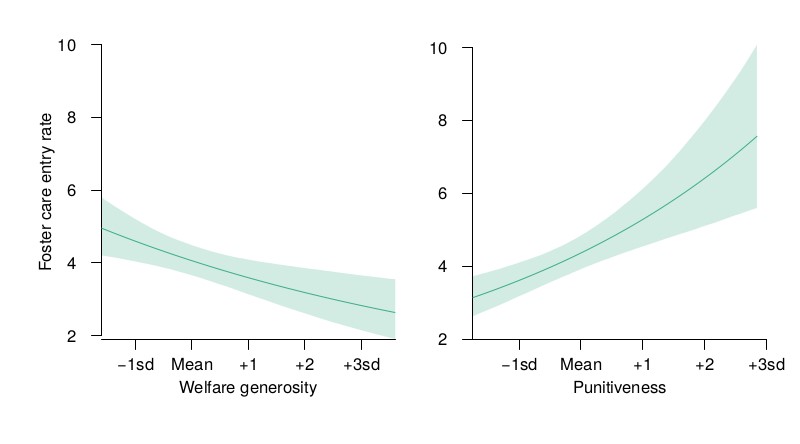

A state’s general approach to managing social problems, or its policy regime, plays an important role in determining whether children experience foster care. If a state has a punitive criminal justice system and meager and restrictive welfare benefits, then it will likely utilize a disruptive approach to respond to child abuse and neglect. If a state has broad and inclusive welfare benefits and a less punitive criminal justice system, it will separate children from their families less frequently.

These relationships between criminal justice, welfare, and child protection work in three ways.

- Social policies play a direct role in increasing or decreasing the incidence of child abuse and neglect. When a parent is incarcerated, their risk of foster care entry increases significantly. If multiple members of a child’s extended family are incarcerated, it taxes the ability of kin to take care of a child when the family is in crisis. Similarly, when welfare benefits are generous and easy to access, it provides families with additional resources and access to critical services (such as medical care), and mitigates the stress and uncertainty associated with deep poverty.

- Social policies reflect institutionalized preferences for certain styles of responses to social problems, like child abuse and neglect. Policymakers prefer interventions that align with their understanding of how the world works. If they believe that crime and poverty are caused by moral failure, they are very likely take a similar view toward child abuse and neglect and prefer harsh and disruptive approaches that separate children from parents. Front line child welfare workers have few alternatives to family separation in states where welfare programs are weak and supportive services are unavailable.

- Child welfare agencies don’t operate in a bureaucratic vacuum. They depend on law enforcement, doctors, teachers, welfare workers, and other public service professionals to monitor children for abuse and neglect and provide services to children and families if child welfare caseworkers decide to intervene. The frequency with which families have contact with these mandated reporters of child abuse and neglect, as well as their ideas about what child abuse and neglect looks like, play a critical role in determining when a child becomes subject of an official report.

Estimating the impact of social policy regimes on foster care

Policy variation leads to big differences in the rates of foster care between states, after adjusting for demographic and political contexts. For example, states with punitive criminal justice systems are expected to place an average of 1.5 more children per 1,000 into foster care annually than states with less punitive criminal justice systems. For a state with an average child population, this translates to 2,200 additional foster care entries per year. States with generous and inclusive welfare programs are expected to place 0.8 fewer children per 1,000 into foster care, compared to states with meager welfare programs.

Figure 2 – Predicted rates of state foster care entry per 1,000 children under variable social policy regimes

Note: Risk factors for child abuse and neglect held constant. Welfare generosity includes TANF benefit levels and ease of enrollment in TANF, SNAP, and Medicaid. Punitiveness includes incarceration per capita, death sentences issued per new prison admission, and police per capita.

Policy regimes also relate to where kids in foster care are placed. Restrictive residential treatment centers and other forms of highly regimented group placements are far less common in states with generous and inclusive welfare systems than in states with meager and restrictive welfare benefits. Variation in welfare systems predicts a difference of about 530 fewer children in institutional foster care in a state with broad and generous welfare programs in a state with an average foster care caseload, compared to a state with weak limited welfare programs.

However, states with both generous welfare benefits and large welfare bureaucracies tend to have slightly higher rates of foster care entry than do states with generous welfare programs and small bureaucracies. This finding suggests that bringing more families into contact with service providers increases the frequency of opportunities for officials to detect and report suspected abuse and neglect.

Reducing foster care caseloads requires a broad approach to reform

Advocates have called for a decreased emphasis on family separation as the primary tool to respond to abuse and neglect for some time. These efforts have been successful in many places, with average foster care caseloads declining by around 20 percent over the last 15 years.

However, larger reductions may depend on improving the quality and accessibility of healthcare, cash, and in-kind benefits, and reducing the degree of severe punishment in state criminal justice regimes. These changes would likely both reduce the incidence of child abuse and neglect, and change the way that policymakers respond to the problem of child maltreatment when they encounter it.

This article is based on the paper, “Saving Children, Controlling Families ” in the American Sociological Review .

Featured image credit: The Children’s Alliance (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2dIYTkr

_______________________________

Frank Edwards – University of Washington

Frank Edwards – University of Washington

Frank Edwards is a PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology at the University of Wisconsin. He studies the relationships between social policy and inequality, and is particularly interested in how and why places pursue different strategies for the surveillance and regulation of families and how institutional forces drive racial inequalities in state intervention.