Despite extensive coverage of early voting as a campaign tool this election cycle, it is not a wholly new phenomenon. In fact, the Clinton campaign’s exploitation of early voting as a part of her ground game has roots in similar efforts by Republican candidates during the 1980s. As Mara Suttmann-Lea explains, candidates can – and do – exploit early voting to their advantage, as it can enable them to more strategic with often limited campaign resources.

Despite extensive coverage of early voting as a campaign tool this election cycle, it is not a wholly new phenomenon. In fact, the Clinton campaign’s exploitation of early voting as a part of her ground game has roots in similar efforts by Republican candidates during the 1980s. As Mara Suttmann-Lea explains, candidates can – and do – exploit early voting to their advantage, as it can enable them to more strategic with often limited campaign resources.

In recent presidential election years, early voting has played a prominent role in the top-ticket candidates’ voter mobilization strategies. They have taken advantage of laws that allow citizens to cast ballots before Election Day without having to provide an excuse. In 2008, Barack Obama launched what was thought to be a pioneering early voting strategy, at least in terms of its sheer scale. In 2012, Obama replicated his 2008 efforts to mobilize early voters. The eventual Republican nominee Mitt Romney followed suit, marshaling an impressive (and expensive) early voting strategy during the Republican primaries that bested many of his opponents, which he carried over into the general election.

Early voting mobilization efforts have featured as heavily, if not more so, in the 2016 presidential election cycle. Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton’s campaign is doubling down on the efforts made by her predecessor in 2008 and 2012. Though it is still too early to definitively measure, it is likely that Clinton’s efforts will ultimately outpace those of Obama’s in the previous presidential election cycles. Unique about this election cycle is that her efforts appear to be so intense that representatives from her campaign and preliminary analysis of early voting returns suggest her victory may be “locked” in some battleground states well before the first ballots are even cast on Election Day.

To be sure, the Republican nominee Donald Trump’s campaign has not neglected early voters. But the two campaigns are using remarkably different strategies. Clinton’s campaign has relied on a traditional ground game and is engaging in a data driven Get Out the “Early” Vote effort. Using data from voter rolls to target likely supporters to which to send absentee ballots, her organization has also made extensive efforts to follow up with individuals requesting ballots to make sure they actually return the marked ballot. For in-person early voting, Clinton’s campaign is using large rallies in multiple locations featuring not only Clinton herself, but also high-profile figures like Elizabeth Warren, Michelle and Barack Obama, her husband, Bill Clinton, and her daughter Chelsea, to turn out early voters. After the rallies, supporters are walked to early voting polling places to cast their ballots.

Trump’s organization, however, has relied almost exclusively on his well-attended rallies to turn out early voters, neglecting a focus on a more traditional ground game. Particularly problematic about this strategy is that Trump and his running mate, Mike Pence, can only be two places at once. He does not appear to be relying on other popular figures to head up early voting rallies as extensively as the Clinton campaign. Without a ground game, it is unclear how much of a dent Trump’s efforts at mobilizing early voters through his rallies alone will make relative to the Clinton campaign’s strategy.

It is worth noting that early voting is not an entirely new campaign tool in presidential elections. Early voting strategies have increased in prominence as more states adopted the reform; what began as a progressive reform aimed at improving voter participation has, over time, had unintended consequences for the behavior of political campaigns and is today a potent political tool for campaign strategists. My research looks at adaptation to this reform by political campaigns and party organizations in six states implementing early voting since the 1970s: Washington, California, Texas, Wyoming, Ohio, and Texas.

Early voting (also known as no-excuse absentee voting) was first adopted in Washington and California in the 1970s with the intent of adding voter convenience and improving participation, but by the 1980s entrepreneurial political campaigns in both states saw an opening for an electoral advantage through the mobilization of early voters. In a 1985 election for a county executive position in Washington, the Republican candidate used a strategy strikingly similar to Clinton’s present day efforts to turn out absentee voters, the first major instance of such an approach in Washington at the time. Although lacking the data availability and technology of contemporary political campaigns, the contours of the early voter mobilization strategy in this small, local election were similar to its modern counterparts: the campaign mailed supporters absentee ballot applications, and followed up in person to make sure they actually cast a ballot. The Republican candidate won the election by a razor thin margin once all of the ballots cast early were accounted for, and the predominant perception was that his strategy had won him the race. Over time, more candidates responded to this “game-changing” local election by adopting similar approaches to mobilizing early voters. This process built on itself, leading to a cumulative diffusion of the strategy to campaigns at all levels of elections across Washington over time.

As more campaigns adopted early voting strategies, political actors marshaled greater resources to sustain these extended voter mobilization efforts to keep pace with their opponents. Similar movements initiated by Republican candidates advanced the use of early voting strategies in California in the 1980s. What’s more, these dynamics are not unique to these particular electoral contexts. Other states in my study had comparable transformations in campaign strategies, though they occurred at a much quicker pace in states adopting the reform in later years.

In short, the early voting strategies that feature so prominently in the 2016 presidential elections have historical origins that stretch well back into the earliest years of the modern period of political campaigning, suggesting this is not a new phenomenon, but one that has only recently gained attention on the national stage of campaigns. This historical evidence also gives us insight into why campaigns had incentivizes to adapt to this reform in the first place. As more campaigns adopted early voting strategies, other political actors, despite a lack of concrete evidence that such adaptations would give them a clear advantage, nevertheless did so out of a fear that not doing so would be more costly for their election chances. Though campaigns readily acknowledged that early voting was a burden in terms of resources (both in terms of finances and the manpower needed to sustain lengthier voter targeting and mobilization efforts), many argued that having an early voting strategy had become a necessary component of their campaign strategies they were hesitant to forgo. Having to garner more resources for early voting strategies was preferable to risking the loss of an electoral advantage.

Despite evidence that campaigns have indeed responded to this reform by adapting their voter mobilization strategies, more difficult to determine is whether early voting actually affects election outcomes independent of other factors. And in an age where most campaigns, at least those operating in highly competitive races, have incentives to develop and implement early voter mobilization strategies, the question of the independent effects of this reform may not be particularly relevant. On the one hand, political scientists contend that early voting doesn’t have much predictive value in terms of actually changing election outcomes; individuals who cast early ballots are likely to have voted the same way if they cast their ballots on Election Day, and are more likely to turn out to vote in the first place. But political consultants see the advantage of early voting for modern campaigns differently: it gives candidates opportunities to be more strategic in their allocation of resources; in close races, if candidates are able to lock up enough early votes from surefire supporters, they can expend more efforts persuading and mobilizing undecided voters who are more likely to wait until Election Day to cast a ballot, if they do so at all. Thus, though campaigns that have more resources than opponents already have the upper hand, this is arguably even more so in states with early voting. In the context of this year’s presidential race, once candidates are confident they have garnered enough support through early votes in certain states, they can shift their resources and attention to the most competitive battleground states, which is precisely what the Clinton campaign appears to be doing.

Given that campaigns are by their very nature strategic organizations, the more pertinent question may not be whether these reforms independently change election outcomes, but whether the decisions of political actors in response to these reforms actually improve their likelihood of success once all of the votes are accounted for—not by changing the way people would have voted—but by allowing campaigns to be more strategic in their allocation of resources and attention. This is an open research question, but one worth exploring, given the predominance of early voting strategies in modern American campaigns.

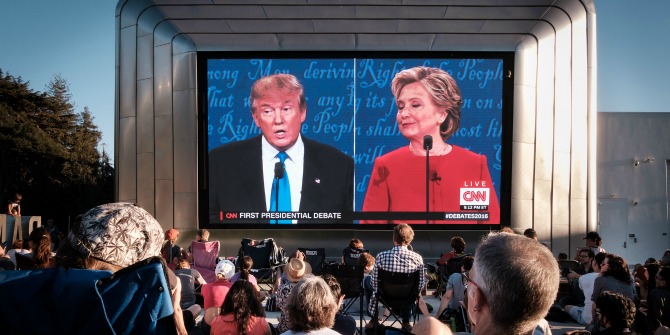

Featured image credit: ep_jhu (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2eGrzek

______________________

Mara Suttmann-Lea – Northwestern University

Mara Suttmann-Lea – Northwestern University

Mara Suttmann-Lea is a PhD Candidate in political science at Northwestern University. Her research is situated at the intersection of state and local electoral institutions, campaigns, political participation, and American political development. Her substantive focus is on how the responses of political actors to changes in election laws can have unintended consequences for American political behavior and institutions.