Despite America’s traditional model of bipartisan cooperation, the US is more politically polarized than ever before. In areas of close party competition, we might expect Democrats and Republicans to search for areas of agreement to work collectively on, given that neither has an outstanding mandate. As Kelsey Hinchliffe and Frances Lee find, however, the opposite is true – borne out of the threat of close elections, party polarization is greater in more electorally competitive states, and this results in less bipartisanship than we might expect.

Despite America’s traditional model of bipartisan cooperation, the US is more politically polarized than ever before. In areas of close party competition, we might expect Democrats and Republicans to search for areas of agreement to work collectively on, given that neither has an outstanding mandate. As Kelsey Hinchliffe and Frances Lee find, however, the opposite is true – borne out of the threat of close elections, party polarization is greater in more electorally competitive states, and this results in less bipartisanship than we might expect.

The increased competition between Democrats and Republicans is perhaps one of the most striking changes in the American political landscape since the 1950s. In particular, increased competition for control of our state legislatures has become the norm. Across a wide range of states, we find majority-party control switching quite frequently between Democrats and Republicans.

An even balance of power between the parties often leads pundits and politicians to claim that voters want the two parties to find common ground. Close elections, especially those that give rise to divided party control, are typically interpreted as mandates for bipartisan cooperation. After the 2014 midterm elections, for example, Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid (D-NV), issued a statement: “The message from voters is clear: They want us to work together.” For his part, Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), said, “When the American people choose divided government . . . it means they want us to look for areas of agreement.”

This conventional political wisdom stands at odds with scholars of state politics. Instead of promoting bipartisan cooperation, scholars since the late 1940s have seen close competition between parties as a driver of partisanship and party conflict. “The parties in the most competitive states,” wrote Austin Ranney in 1976, “are likely to have . . . the highest cohesion in the legislatures. . . . [Meanwhile,] party cohesion is generally very low in the one-party and modified one-party states.”

Why should increased competition exacerbate polarization?

The underlying logic is intuitive. When a political party either fears the loss of power or perceives opportunities to win power, its members have stronger incentives to step up their organizational efforts. By the same logic, a lack of competition tends to atrophy party organization. Parties have little reason to invest in organization when the party in power perceives no threat and the party out of power sees no prospects for change.

Partisan incentives are not just confined to the organization and waging of electoral campaigns external to the legislature. They extend into internal legislative politics. “Opposing parties have as a prime objective defeating each other in elections,” wrote Alan Rosenthal in 1990. “To do this, each tries to discredit the other, not only during an election campaign but also during the conduct of government.” Close competition for party control fosters partisan contentiousness, as legislators look for opportunities to criticize and embarrass their opponents.

Estimating the impact of party competition on political polarization

To illustrate, we can present the relationship between each state’s legislative party polarization score and party competition using three different measures of two-party competition. For our dependent variable, we rely on the 2014 Shor-McCarty polarization scores for both the upper and lower chambers of each state legislature.

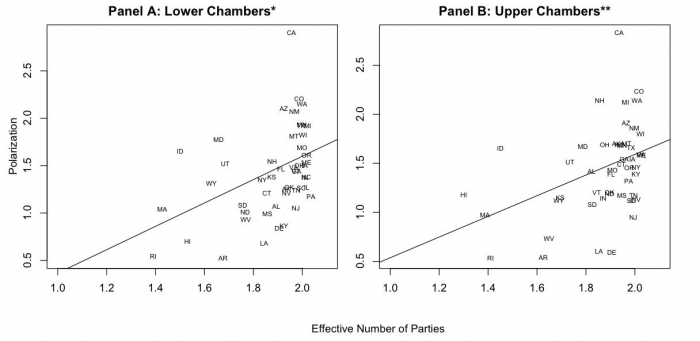

Our first measure of two-party competition captures the effective number of political parties in the state. In two-party systems, this measure reaches its maximum when the two parties hold an equal number of legislative seats. As Figure 1 shows, as the effective number of political parties in a state gets closer to two, state legislative polarization also increases.

Figure 1 – Mean State Legislative Party Polarization, by Effective Number of Parties in the State, 1995-2013

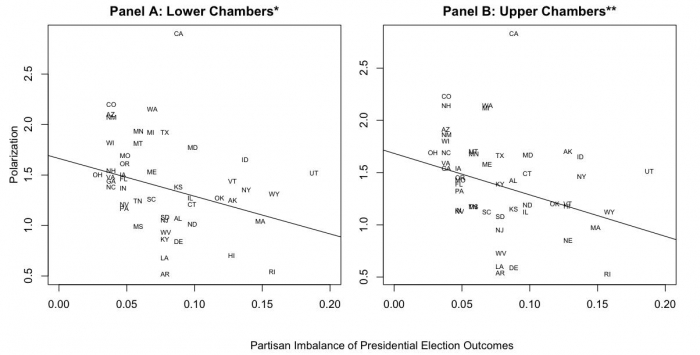

Our second measure of two-party competition captures the states’ two-party margin in presidential elections. In states where presidential candidates win narrowly, we should find more legislative party polarization than in “blow-out” states. In Figure 2, we see lower levels of party polarization, a score of about 1.20, in states where a presidential candidate wins by a landslide compared to scores of approximately 1.54, a 28% increase, in highly competitive states.

Figure 2 – Mean State Legislative Party Polarization, by Competitiveness of Presidential Elections, 1995-2013

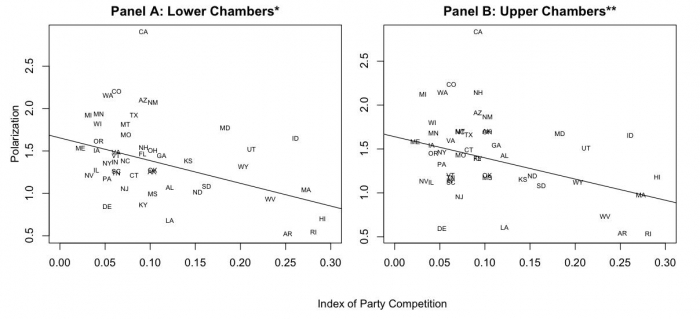

Our final measure of two-party competition is a composite measure combining party competition for the governorship and control of the upper and lower chambers of the state legislature, resulting in an index where states in which one party dominates having higher scores and states that are more two-party competitive having lower scores. Again, similar to the previous measures, Figure 3 demonstrates that across both upper and lower chambers, the more two-party competitive states have more polarized legislatures.

Figure 3 – Mean State Legislative Party Polarization, by Index of State Party Competition, 1995-2013

Regardless of how one chooses to measure competition, states with higher levels of competition between the two parties show greater levels of polarization. Even when considering additional factors that may also influence party competition and polarization, increased party competition still has a measurable and significant effect on the level of state legislative party polarization.

States considered to be uncompetitive by our third measure of two-party competition, such as Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Hawaii and West Virginia had a predicted party polarization score of 1.17 in their lower chambers will highly competitive states by this measure such as Michigan, Maine, Iowa, Illinois and Wisconsin, scored a 1.41, a significant increase. In the upper chambers, uncompetitive states had a predicted party polarization score of 1.27 while competitive states had a predicted party polarization score of 1.95. Again, a meaningful increase.

Findings suggest that party competition and bipartisan cooperation pull in contrary directions

Taken together, we find a clear pattern in which state legislatures in two-party competitive states tend to exhibit more party polarization than do legislatures in states where one party is completely dominant. These findings align well with a theory that party competition for control of governing institutions encourages politicians to seek out ways to distinguish their party from the opposition. In a legislative setting, this is likely to take the form of bringing up issues designed to elicit and then communicate partisan cleavages to external constituencies. In the congressional context, this tactic is often referred to as staging “message votes.” The relationship also mirrors the documented effect of competition on individual congressional races: candidates in competitive elections are more likely to draw clear distinctions from their opponents while candidates in uncompetitive elections prefer to avoid controversial issues.

Today, however, the range of variation in state two-party competitiveness has narrowed considerably. Most states now are two-party competitive, at least to some extent. If one were able to extend this study back in time, the patterns would likely be stronger. As a whole, these findings point to continuing disappointment for pundits and politicians who hope that close elections will encourage politicians to seek common ground across party lines. There is no evidence here that close party competition incentivizes legislative bipartisanship. To the contrary, the findings suggest that party competition and bipartisan cooperation pull in contrary directions. State legislatures in more party competitive contexts exhibit sharper party conflict.

This article is based on the paper, “Party Competition and Conflict in State Legislatures” in State Politics and Policy Quarterly.

Featured image credit: Colorado Senate GOP (Flickr, Public Domain)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2er5t1n

______________________

Kelsey L. Hinchliffe – University of Maryland

Kelsey L. Hinchliffe – University of Maryland

Kelsey L. Hinchliffe is a graduate student in the Department of Government and Politics at the University of Maryland. Her research focuses on political parties, congressional campaigns and polarization.

Frances E. Lee – University of Maryland

Frances E. Lee – University of Maryland

Frances E. Lee is a Professor in the Department of Government and Politics at the University of Maryland specializing in the study of Congress, political parties, and policymaking. She is author of Insecure Majorities: Congress and the Perpetual Campaign and Beyond Ideology: Politics, Principles, and Partisanship in the U.S. Senate.